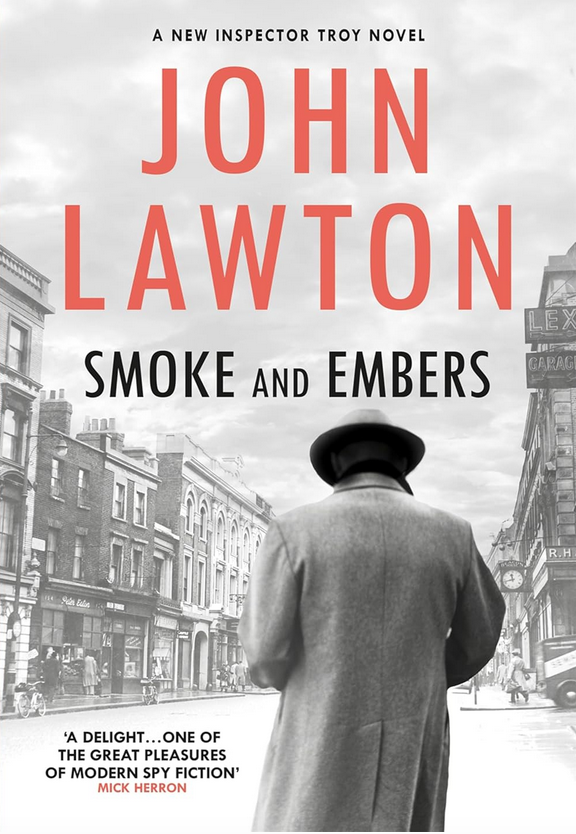

Fans of John Lawton’s wonderful Fred Troy books, which began with Blackout (1995) will be delighted that the enigmatic London copper, with his intuitive skills and shameless womanising, makes an appearance here. Throughout the series Troy, son of an exiled Russian aristocrat and media baron, subsequently crosses the paths of all manner of real life characters including, memorably, Nikita Kruschev. For those interested in Troy’s back-story, this link Fred Troy may be of interest. He is not, however, central to this story. We rub shoulders with him, for sure, and also with his brother Rod, a Labour MP who serves in Clement Attlee’s postwar government. We are also reminded of characters from the previous novels – Russian soldier and spy Larissa Tosca, and the doomed Auschwitz cellist Meret Voytek. The book begins with sheer delight.

“Brompton Cemetery was full of dead toffs. Just now Troy was standing next to a live one. John Ernest Stanhope FitzClarence Ormond Brack, 11th Marquis of Fermanagh, eligible bachelor, man-about-town, and total piss artist.”

As ever in Lawton’s novels, the timeframe shifts. He takes us to 1945, the year of Hitler’s final annihilation, and to 1960 and the capture of Adolf Eichmann. Central to story is the fate of Europe’s Jews, their destruction at the hands of the Nazis, and then their almost complete rejection by Poland, Palestine, Britain, America and Russia after what was, for them, a hollow victory in 1945. Lawton’s story hinges on the lives of three young men. First is Sam Fabian, a German Jew, a mathematician and physicist who is saved from Auschwitz by a misfiring SS Luger and a compassionate Red Army officer. Then we have Jay Heller, a gifted English Jew who, immediately after joining up in 1940, is head hunted into the British intelligence services. Finally, we have Klaus LInz von Niegutt, minor member of what remains of the German aristocracy, who finds his way – or is led – into the SS. He is, however, not a violent man, and only does the bare minimum to remain ‘one of the chosen’. His significance in the novel is that he was one of the scores of staff – cooks, clerks and secretaries – who were in Hitler’s bunker in those fateful days at the end of April 1945.

With an audacious plot twist, Lawton gets Sam Fabian to England, where he finds work with a millionaire German Jew called Otto Ohnherz whose empire while not overtly criminal, is founded on the success of ventures that, while not quite illegal, are extremely profitable. He can afford to employ the best professionals. This is his barrister:

“It was said of Jago that by the time he’d finished a cross-examination, the witness would be swearing Tom, Tom, the Piper’s son had been nowhere near the pig and had in fact been eating curds and whey with Miss Muffet at the time.”

When Ohnerz dies, Jay takes over the empire, and becomes involved with maintaining Ohnerz’s rental property business. While making sure the money still rolls in, he sets out to improve the houses, particularly those rented by tenants recently arrived from the Caribbean. It is when Jay’s broken body is found on the pavement below his headquarters that the story seemingly takes a turn towards the impossible. What Troy and the pathologist discover certainly had me scratching my head for a while. Lawton’s use of separate narratives and times allows him to set a seemingly unsolvable conundrum regarding the ultimate fates of Jay, Sam and Klaus. To be fair, he provides clues, using a rather clever literary device. I won’t reveal what it is, but when you reach the last section of the book, you may need to revisit earlier pages. Smoke and Embers shows a profound understanding of the dark realpolitik that followed the end of the war in Europe, and is full of Lawton’s customary wit and wizardry. It is published by Grove Press UK and is available now.

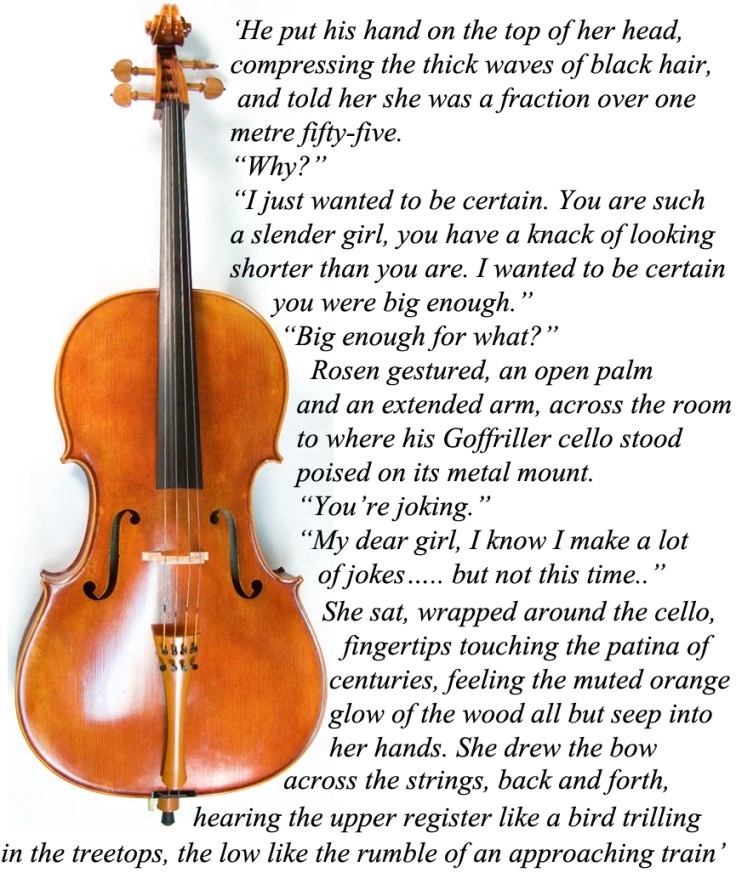

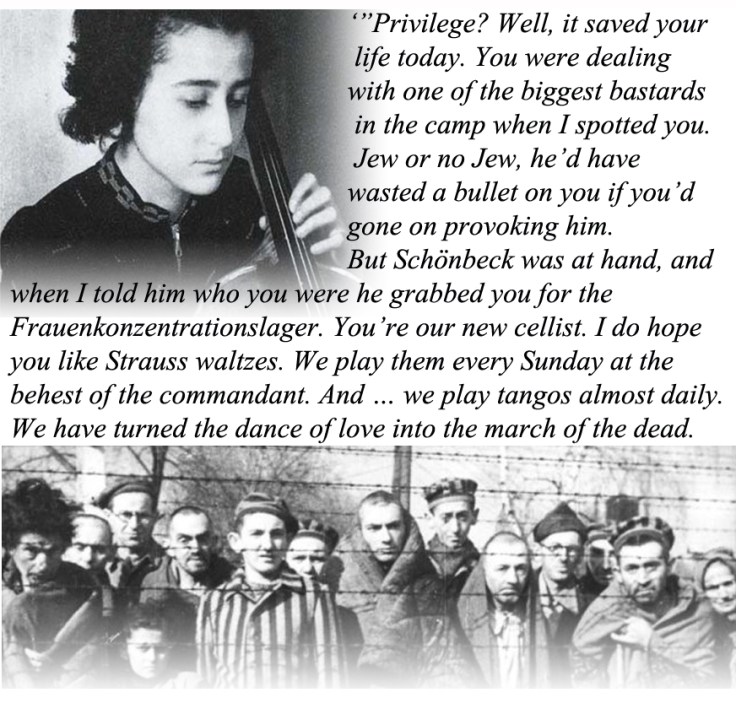

Some writers who have authored different series occasionally allow the main characters to meet each other, provided that they are contemporaries, of course. I’m pretty sure that Michael Connolly has allowed Micky Haller to bump into Harry Bosch, while Sunny Randall and Jesse Stone certainly knew each other in their respective series by Robert J Parker. Did Spenser ever join them in a (chaste) threesome? I don’t remember. John Lawton’s magnificent Fred Troy series ended with Friends and Traitors (2017), and since then he has been writing the Joe Wilderness books, of which this is the fourth. I can report, with some delight, that in the first few pages we not only meet Fred, but also Meret Voytek, the tragic heroine of A Lily of the Field, and her saviour – Fred’s sometime lover and former wife, Larissa Tosca. As an aside, for me A Lily of the Field is not only the best book John Lawton has ever written, but the most harrowing and heartbreaking account of Auschwitz ever penned. Click the link below to read more.

Some writers who have authored different series occasionally allow the main characters to meet each other, provided that they are contemporaries, of course. I’m pretty sure that Michael Connolly has allowed Micky Haller to bump into Harry Bosch, while Sunny Randall and Jesse Stone certainly knew each other in their respective series by Robert J Parker. Did Spenser ever join them in a (chaste) threesome? I don’t remember. John Lawton’s magnificent Fred Troy series ended with Friends and Traitors (2017), and since then he has been writing the Joe Wilderness books, of which this is the fourth. I can report, with some delight, that in the first few pages we not only meet Fred, but also Meret Voytek, the tragic heroine of A Lily of the Field, and her saviour – Fred’s sometime lover and former wife, Larissa Tosca. As an aside, for me A Lily of the Field is not only the best book John Lawton has ever written, but the most harrowing and heartbreaking account of Auschwitz ever penned. Click the link below to read more.

He is no James Bond figure, however. His dark arts are practised in corners, and with as little overt violence as possible. Hammer To Fall begins with a flashback scene,establishing Joe’s credentials as someone who would have felt at home in the company of Harry Lime, but we move then to the 1960s, and Joe is in a spot of bother. He is thought to have mishandled one of those classic prisoner exchanges which are the staple of spy thrillers, and he is sent by his bosses to weather the storm as a cultural attaché in Finland. His ‘mission’ is to promote British culture by traveling around the frozen north promoting visiting artists, or showing British films. His accommodation is spartan, to say the least. In his apartment:

He is no James Bond figure, however. His dark arts are practised in corners, and with as little overt violence as possible. Hammer To Fall begins with a flashback scene,establishing Joe’s credentials as someone who would have felt at home in the company of Harry Lime, but we move then to the 1960s, and Joe is in a spot of bother. He is thought to have mishandled one of those classic prisoner exchanges which are the staple of spy thrillers, and he is sent by his bosses to weather the storm as a cultural attaché in Finland. His ‘mission’ is to promote British culture by traveling around the frozen north promoting visiting artists, or showing British films. His accommodation is spartan, to say the least. In his apartment: So far, so funny – and Lawton (right) is in full-on Evelyn Waugh mode as he sends up pretty much everything and anyone. The final act of farce in Finland is when Joe earns his keep by sending back to London, via the diplomatic bag, several plane loads of …. well, state secrets, as one of Joe’s Russian contacts explains:

So far, so funny – and Lawton (right) is in full-on Evelyn Waugh mode as he sends up pretty much everything and anyone. The final act of farce in Finland is when Joe earns his keep by sending back to London, via the diplomatic bag, several plane loads of …. well, state secrets, as one of Joe’s Russian contacts explains:

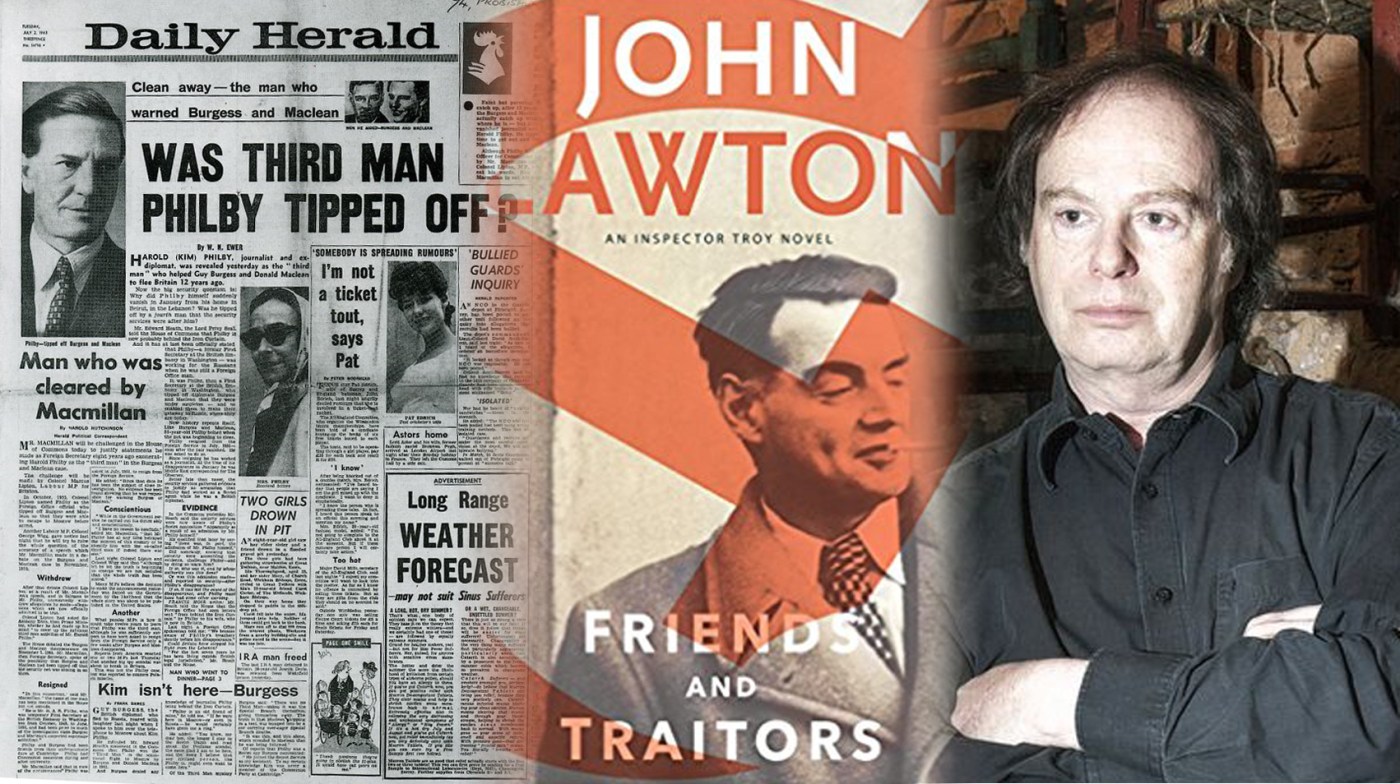

Friends and Traitors focuses mostly on the 1951 defection – and its aftermath – of intelligence officer Guy Burgess, to the Soviet Union. A huge embarrassment to the British government at the time, it was also about personalities, Britain’s place in the New World Order – and its attitudes to homosexuality. Burgess’s usefulness to the Soviets was largely symbolic, but the crux of the story is the events surrounding Burgess’s regrets, and heartfelt wish to come home. Troy interviews him in a Vienna hotel.

Friends and Traitors focuses mostly on the 1951 defection – and its aftermath – of intelligence officer Guy Burgess, to the Soviet Union. A huge embarrassment to the British government at the time, it was also about personalities, Britain’s place in the New World Order – and its attitudes to homosexuality. Burgess’s usefulness to the Soviets was largely symbolic, but the crux of the story is the events surrounding Burgess’s regrets, and heartfelt wish to come home. Troy interviews him in a Vienna hotel.

Lawton (right) was born in 1949, so would have only the vaguest memories of growing up in an austere and fragile post-war Britain, but he is a master of describing the contradictions and social stresses of the middle years of the century. Here, he describes Westcott, a notoriously persistent MI5 interrogator, sent to quiz Troy on the events in Vienna:

Lawton (right) was born in 1949, so would have only the vaguest memories of growing up in an austere and fragile post-war Britain, but he is a master of describing the contradictions and social stresses of the middle years of the century. Here, he describes Westcott, a notoriously persistent MI5 interrogator, sent to quiz Troy on the events in Vienna:

John Lawton is a master of historical fiction set in and around World War II. His central character is Fred Troy, a policeman of Russian descent. His emigré father is what used to be called a ‘Press Baron’. Fred’s brother Rod will go on to become a Labour Party MP in the 1960s, but is interned during the war. His sisters are bit players, but memorable for their sexual voracity. Neither man nor woman is safe from their advances.

John Lawton is a master of historical fiction set in and around World War II. His central character is Fred Troy, a policeman of Russian descent. His emigré father is what used to be called a ‘Press Baron’. Fred’s brother Rod will go on to become a Labour Party MP in the 1960s, but is interned during the war. His sisters are bit players, but memorable for their sexual voracity. Neither man nor woman is safe from their advances.

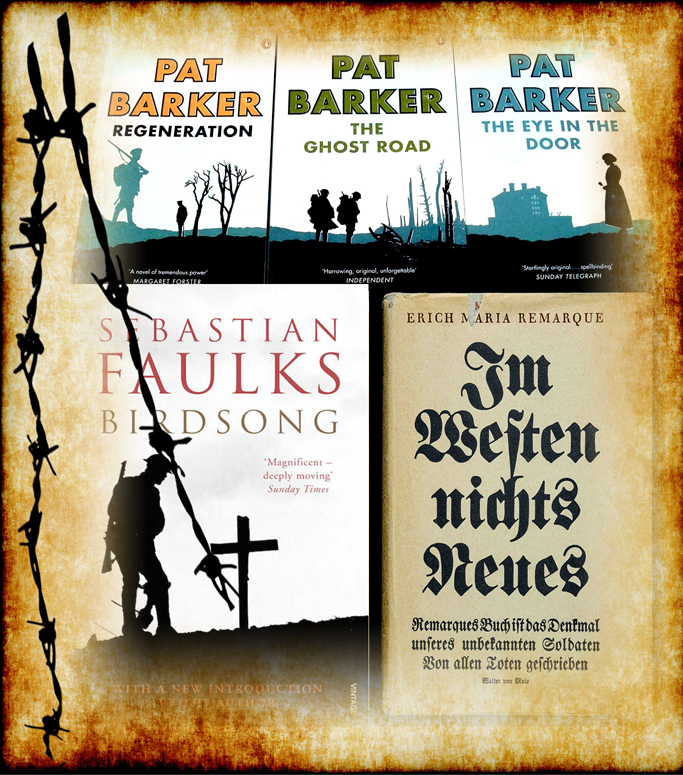

What needs to be held up like a bright lantern in our search for good WWI crime fiction, is the fact that those six years are like no other in British history. They have produced a mythology which is unique in modern memory, and with it a collection of tropes, images, phrases and conventions, all of which find their way into the consciousness of writers and readers. Military historians tell only part of the story: the Alan Clark theory of The Donkeys and the anti-war polemic of the the 1960s and 70s has one version of events; more recent accounts of the war by revisionist historians such as John Terrain and Gary Sheffield tell another tale altogether. In considering books and writers for this feature I have used two criteria. Firstly, there must be crime involved that is distinct from the licensed slaughter of wartime and, secondly, the events of the war must cast their shadows over the narrative either in a contemporary sense or in the form of a social or political legacy.

What needs to be held up like a bright lantern in our search for good WWI crime fiction, is the fact that those six years are like no other in British history. They have produced a mythology which is unique in modern memory, and with it a collection of tropes, images, phrases and conventions, all of which find their way into the consciousness of writers and readers. Military historians tell only part of the story: the Alan Clark theory of The Donkeys and the anti-war polemic of the the 1960s and 70s has one version of events; more recent accounts of the war by revisionist historians such as John Terrain and Gary Sheffield tell another tale altogether. In considering books and writers for this feature I have used two criteria. Firstly, there must be crime involved that is distinct from the licensed slaughter of wartime and, secondly, the events of the war must cast their shadows over the narrative either in a contemporary sense or in the form of a social or political legacy.

A LILY OF THE FIELD by John Lawton

A LILY OF THE FIELD by John Lawton