This occasional series of retrospective reviews seeks to ask and – hopefully – answer a few simple questions about crime novels from the past. Those questions include:

How was the book received at the time?

How does it read now, decades after publication?

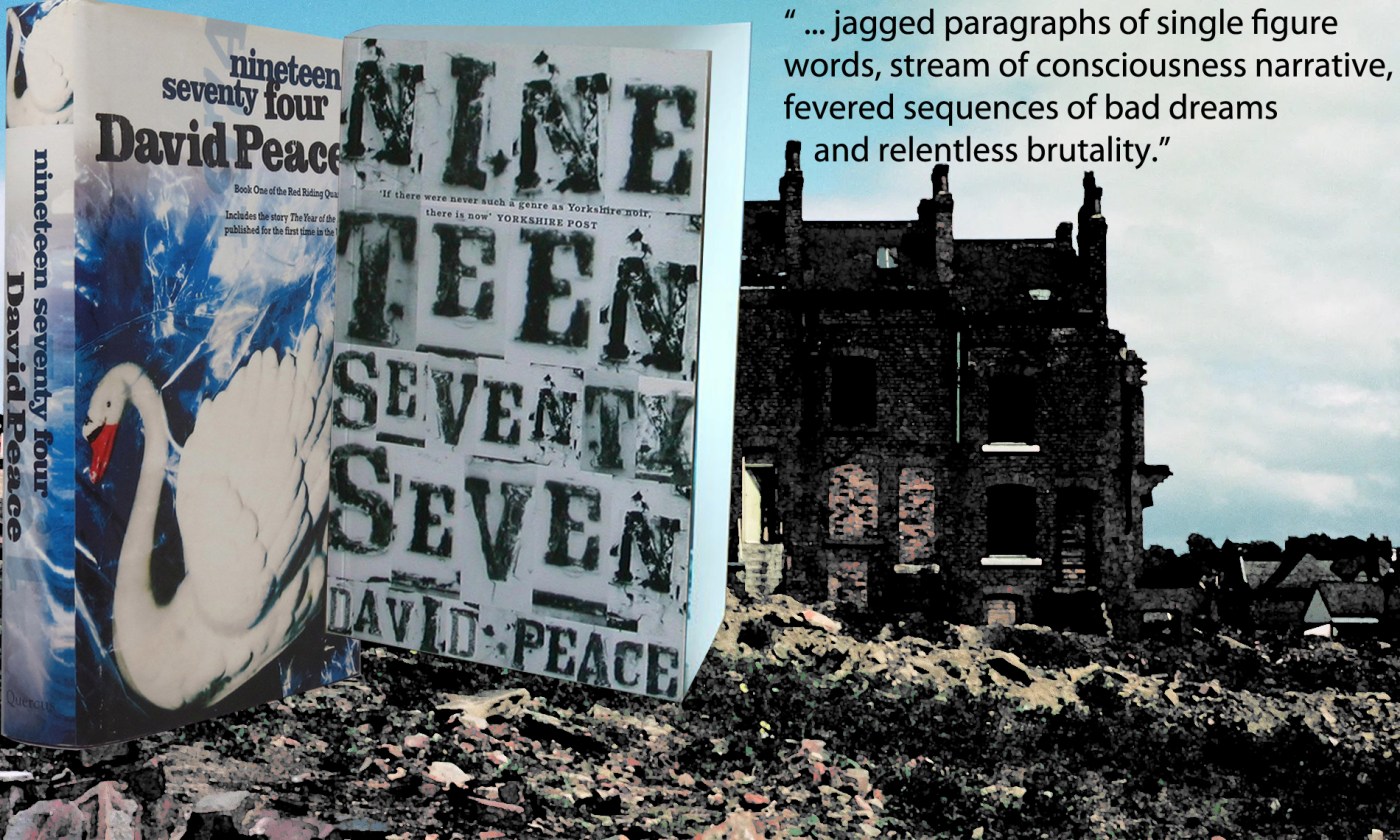

I have departed from the usual format by examining two books, published in 1999 and 2000 by Serpents Tail. They were the first two in a quartet of novels by David Peace (left), which have come to be known as the Red Riding Quartet. The books are set in West Yorkshire, and each references real criminal events of the time

1974 is set in a bleak December in Leeds. Edward Dunford is the crime correspondent for a local paper which publishes daily morning and evening editions. He is keen to make his mark, but is overshadowed by his more experienced predecessor, Jack Whitehead. Mourning the recent death of his father, Dunford covers the abduction of a schoolgirl, Clare Kemplay, whose body is later found sexually assaulted and horrifically mutilated. Wings, torn from a swan in a local park, have been been crudely stitched to the little girl’s back. Dunford is convinced that the killing is connected to earlier missing children, but then his search for answers becomes tangled up with crooked property dealers, blackmail, corrupt politicians and a dystopian police force. Dunford receives several graphically described beatings, there is violent, joyless sex and, in almost constant rain, the neon-lit motorways and carriageways around Leeds and Wakefield take on a baleful presence of their own.

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence. In a nod to a real life case David Peace has a man called Michael Myshkin, clearly with mental difficulties, arrested for the Clare’s murder. It is obvious that this refers to the ordeal of Stefan Kiszko (right) – arrested, tried and convicted for the murder of Lesley Molseed in 1975. He remained in prison until 1992, but was then acquitted and released after the case was re-examined.

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence. In a nod to a real life case David Peace has a man called Michael Myshkin, clearly with mental difficulties, arrested for the Clare’s murder. It is obvious that this refers to the ordeal of Stefan Kiszko (right) – arrested, tried and convicted for the murder of Lesley Molseed in 1975. He remained in prison until 1992, but was then acquitted and released after the case was re-examined.

1977 is a re-imagining of the how the Yorkshire Ripper murders began to imprint themselves on the public’s imagination, and baffle police for many years. It is the early summer and we are reunited with many characters from 1974, including Jack Whitehead, DS Bob Fraser and several of the senior police officers who made Eddie Dunford’s life a misery. Apart from the obvious mark of Peace’s style – jagged paragraphs of single figure words, stream of consciousness narrative, fevered sequences of bad dreams and relentless brutality, there are other thematic links. Eddie Dunford’s father has just died, shriveled to a husk by cancer; Bob Fraser’s father in law is just days away from death from the same disease. Both Whitehead and Frazer have their sexual demons, and in Fraser’s case it is a prostitute called Janice who he first arrested, and then became transfixed by. She is murdered, and he is arrested.

When straightforward narrative clarity is abandoned in favour of literary special effects, the downside is that it is sometimes hard work to know who is imaging what. Someone in 1977 is referencing the Whitechapel murders of 1888 and, in particular, the destruction of Mary Jane Kelly in Millers Court. Likewise, someone is using the slightly artificial jollity of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee as a sour counterpoint to the carnage being inflicted on the back streets of Leeds. The novel ends inconclusively, but it seems that both Whitehead and Fraser become the victims of their obsessions.

It is worth looking at the chronology of what I call ‘brutalist’ crime fiction (aka British Noir). The grand-daddy of them all is probably Jack’s Return Home, (1970) later re-imagined as Get Carter, and featuring corrupt businessmen, although there is little or nopolice involvement. This was Ted Lewis’s breakthrough novel, but aficionados will argue that his GBH – a decade later – is even better. 1974 and 1977 are explicit, bleak and visceral, but we would do well to remember that I Was Dora Suarez, the most horrific of Derek Raymond’s Factory novels, was published in 1990, and featured a similar leitmotif to 1974 – that of wounds, pain and suffering. To revisit IWDS click the link below.

https://fullybooked2017.com/tag/i-was-dora-suarez/

As compelling as these two novels are, David Peace wasn’t exploring ground unvisited by earlier writers. Tastes and descriptions in crime fiction are all relative. Val McDermid’s excellent Tony Hill/Carol Jordan novels were lauded as visiting dark places where other writers had feared to tread, but they were relatively mild, at least in terms of gore and viscera. Great stories, yes, from a fine writer, but not exactly pushing boundaries. Given the free use of vernacular words to describe ethnicity and sexual preferences, had Peace’s novels been submitted by an unknown writer in 2023, it is improbable that the books would see the light of day, given the cultural eggshells on which mainstream publishers seem to tiptoe.

Final verdict? I’ll answer the two questions I posed at the top of this piece. Firstly, the contemporary reactions were pretty enthusiastic, and included, from Time Out (remember that?):

“The finest work of literature I’ve read this year – extraordinary and original”

The Independent on Sunday enthused:

“Vinnie Jones should buy the film rights fast!”

The Guardian offered:

“A compelling fiction – Jacobean in its intensity.”

They are not wrong about the books, but I suspect that the soundbites were from reviewers who perhaps did not have a very great overview of what had gone before. As for how they read these days, I came to them new, via a Christmas present from my son, and they certainly grab you by the throat. I read both books in two days but did I care very much about what happened to Eddie Dunford, Jack Whitehead or Bob Fraser? Not much, to be honest. The Aeschylean/Shakespearean view of a tragic figure is that he/she is someone who is basically a decent person brought low by a combination of fate and accident. For me, Eddie, Jack and Bob might have appeared to tick the first box, but actually didn’t. The two later books in the quartet were published in 2001(1980) and 2002 (1983) so they fall outside this remit. As for Vinnie Jones buying the film rights, the books were filmed as a trilogy, more or less omitting 1977 altogether. They were broadcast in March 2009.

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence.

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence.

Keith Dixon’s Porthaven is a fictional town on England’s south coast. It doesn’t seem woke or disfunctional enough to be Brighton, maybe neither big nor rough enough to be Portsmouth or Southampton, so it’s maybe a mix of all three, seasoned with a dash of Newhaven and Peacehaven. Inspector Walter Watts is a Porthaven copper. He is middle-aged, deeply cynical, overweight, and a man certainly not at ease with himself – or many others – but a very good policeman. When a young woman, later identified as Cheryl Harris, is found murdered on a piece of waste ground, the only thing Watts accomplishes on his visit to the scene is that his sarcastic exchanges with a female CSI officer result in in an official complaint, and him being moved off the case. From the sidelines, Watts knows that whoever killed the young woman was definitely trying to pass on a message. The woman’s face has been obliterated by a concrete slab, with her mobile ‘phone jammed into what was left of her mouth.

Keith Dixon’s Porthaven is a fictional town on England’s south coast. It doesn’t seem woke or disfunctional enough to be Brighton, maybe neither big nor rough enough to be Portsmouth or Southampton, so it’s maybe a mix of all three, seasoned with a dash of Newhaven and Peacehaven. Inspector Walter Watts is a Porthaven copper. He is middle-aged, deeply cynical, overweight, and a man certainly not at ease with himself – or many others – but a very good policeman. When a young woman, later identified as Cheryl Harris, is found murdered on a piece of waste ground, the only thing Watts accomplishes on his visit to the scene is that his sarcastic exchanges with a female CSI officer result in in an official complaint, and him being moved off the case. From the sidelines, Watts knows that whoever killed the young woman was definitely trying to pass on a message. The woman’s face has been obliterated by a concrete slab, with her mobile ‘phone jammed into what was left of her mouth. Watts was brought up by his father – and in boarding schools – after his mother left the home. There has been no contact with her from that day to this, until he receives a message from the desk sergeant at Porthaven ‘nick’ simply saying that his mother had ‘phoned, and would he call her back on the number provided. This thread provides an interesting and complex counterpoint to the police investigation into the killing of Cheryl Harris. It also allows Keith Dixon (right) to better define Watts as a person; on the one hand he is aloof, selfish, socially abrasive and enjoys showing his mental superiority; on the other, he is vulnerable, unsure, and shaped by a childhood lacking conventional affection.

Watts was brought up by his father – and in boarding schools – after his mother left the home. There has been no contact with her from that day to this, until he receives a message from the desk sergeant at Porthaven ‘nick’ simply saying that his mother had ‘phoned, and would he call her back on the number provided. This thread provides an interesting and complex counterpoint to the police investigation into the killing of Cheryl Harris. It also allows Keith Dixon (right) to better define Watts as a person; on the one hand he is aloof, selfish, socially abrasive and enjoys showing his mental superiority; on the other, he is vulnerable, unsure, and shaped by a childhood lacking conventional affection.

Without giving the game away, it is in Brother Dominic’s previous life where the clues are to be found, but answers don’t come easy for Cross and Ottey. Although there was a very clever plot twist involving the identity of the killer, I was far more involved with George Cross as a person than wondering who murdered Brother Dominic.The relationship between Cross and his father, the discombobulating effect of the re-emergence of his mother – lost to him since she left the family home when he was five – and his attraction to the unambiguous world of order, silence and simplicity of Dominic’s fellow monks, all contribute to the power of this compelling read.

Without giving the game away, it is in Brother Dominic’s previous life where the clues are to be found, but answers don’t come easy for Cross and Ottey. Although there was a very clever plot twist involving the identity of the killer, I was far more involved with George Cross as a person than wondering who murdered Brother Dominic.The relationship between Cross and his father, the discombobulating effect of the re-emergence of his mother – lost to him since she left the family home when he was five – and his attraction to the unambiguous world of order, silence and simplicity of Dominic’s fellow monks, all contribute to the power of this compelling read.