While nothing beats a good book, detectives on TV come a close second. At the age of 72 I have seen a fair few of these small screen sleuths, and I’ve made a purely subjective list of the best twenty five. My shortlist ran to well over sixty, and if some who didn’t make the cut are your personal favourites, then please accept my commiserations. It’s also worth saying that of my twenty five, the majority are adaptations of books.

First, my criteria for inclusion. My choices are all British productions featuring British actors and, with two exceptions, mostly British settings. I’ve excluded ensemble police procedurals such as Z Cars, The Bill and Waking The Dead. I have, regretfully, left out my all time classic TV crime drama Callan, because dear old David wasn’t so much a detective as an enforcer or a cleaner-up of the messes created by his shadowy employers. Each of my choices has a readily identifiable – and sometimes eponymous – leading character, to the extent that were the man or woman on the proverbial omnibus shown a photograph of, for example, George Baker, they would say, “Ah yes – Wexford!” Please feel free to vent your outrage at omissions or inclusions via the usual social media networks, but here goes:

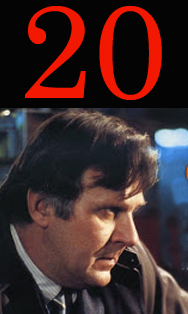

Victorian coppers were not new to TV when this Sergeant Cribb, based on the excellent Peter Lovesey novels, first aired. There had already been several attempts at the Holmes canon, and way back in 1963 John Barrie starred as Sergeant Cork. Although a serial, rather than a series, the 1959 version of The Moonstone featured the great Patrick Cargill as Sergeant Cuff, possibly the first fictional detective. Where Sergeant Cribb came to life was through the superbly dry and acerbic characterisation of Alan Dobie, aided and abetted by the ever-dependable William Simons. Neither did it hurt that most of the episodes were written by Peter Lovesey himself. (1980 – 1981)

Victorian coppers were not new to TV when this Sergeant Cribb, based on the excellent Peter Lovesey novels, first aired. There had already been several attempts at the Holmes canon, and way back in 1963 John Barrie starred as Sergeant Cork. Although a serial, rather than a series, the 1959 version of The Moonstone featured the great Patrick Cargill as Sergeant Cuff, possibly the first fictional detective. Where Sergeant Cribb came to life was through the superbly dry and acerbic characterisation of Alan Dobie, aided and abetted by the ever-dependable William Simons. Neither did it hurt that most of the episodes were written by Peter Lovesey himself. (1980 – 1981)

I am sure the loss is all mine, but of the Golden Age female crime writers I have found Agatha Christie the least interesting, despite her ingenious plotting and ability to create atmosphere. Mea Culpa, I suppose, but it would be reckless not to include Miss Marple in this list. Geraldine McEwan and Julia McKenzie have their admirers, but Joan Hickson is, surely, the Miss Marple? Her series (1984 – 1992) was certainly the most canonical and, if the anecdote is to be believed, Agatha Christie herself once sent a note to the younger Hickson hoping that she would, one day, play the Divine Miss M.

I am sure the loss is all mine, but of the Golden Age female crime writers I have found Agatha Christie the least interesting, despite her ingenious plotting and ability to create atmosphere. Mea Culpa, I suppose, but it would be reckless not to include Miss Marple in this list. Geraldine McEwan and Julia McKenzie have their admirers, but Joan Hickson is, surely, the Miss Marple? Her series (1984 – 1992) was certainly the most canonical and, if the anecdote is to be believed, Agatha Christie herself once sent a note to the younger Hickson hoping that she would, one day, play the Divine Miss M.

Small, aggressive, punchy and with hard earned bags under his eyes, Mark McManus was Taggart. Before he drank himself to death, McManus drove the Glasgow cop show, repaired its engine and polished its bodywork to perfection. It was Scottish Noir before the term had come into common parlance. Bleak, abrasive, unforgiving and with a killer theme song, Taggart was a one-off. The series limped on after McManus died but it was never the same again. (1983 – 1995)

Small, aggressive, punchy and with hard earned bags under his eyes, Mark McManus was Taggart. Before he drank himself to death, McManus drove the Glasgow cop show, repaired its engine and polished its bodywork to perfection. It was Scottish Noir before the term had come into common parlance. Bleak, abrasive, unforgiving and with a killer theme song, Taggart was a one-off. The series limped on after McManus died but it was never the same again. (1983 – 1995)

Who knows what the lady herself would have made of David Suchet’s Poirot? Her family are said to have approved, and for sheer over-the-top bravura, Suchet’s mincing and mannered portrayal has to be admired. The production values were always immense from day one in 1989 and by the time the series finished in 2013, every major work by Agatha Christie which featured Poirot had made its way onto the screen. The supporting cast was every bit as good, with Hugh Fraser as Hastings and Philip Jackson as the permanently one-step-behind Inspector Japp.

Who knows what the lady herself would have made of David Suchet’s Poirot? Her family are said to have approved, and for sheer over-the-top bravura, Suchet’s mincing and mannered portrayal has to be admired. The production values were always immense from day one in 1989 and by the time the series finished in 2013, every major work by Agatha Christie which featured Poirot had made its way onto the screen. The supporting cast was every bit as good, with Hugh Fraser as Hastings and Philip Jackson as the permanently one-step-behind Inspector Japp.

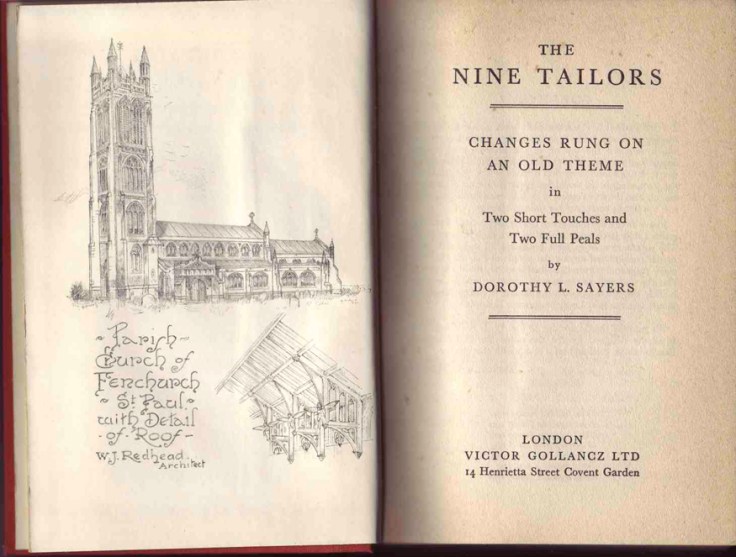

For me, the Golden Age Queen was Dorothy L Sayers and my permanent Best Ever Crime Novel is The Nine Tailors, so it is a relatively brief series (1972 – 1975) featuring Lord Peter Wimsey that makes its way into this list. Some DLS buffs refer the slightly more cerebral Edward Petherbridge version, but my vote goes to Ian Carmichael. He played up the more foppish and scatty side of Wimsey’s nature, but he also managed to convey, underneath the gaiety, the fact that Wimsey was something of a war hero, and his recovery from wounds and shell shock was due in no small part to his relationship with his former Sergeant, Mervyn Bunter.

For me, the Golden Age Queen was Dorothy L Sayers and my permanent Best Ever Crime Novel is The Nine Tailors, so it is a relatively brief series (1972 – 1975) featuring Lord Peter Wimsey that makes its way into this list. Some DLS buffs refer the slightly more cerebral Edward Petherbridge version, but my vote goes to Ian Carmichael. He played up the more foppish and scatty side of Wimsey’s nature, but he also managed to convey, underneath the gaiety, the fact that Wimsey was something of a war hero, and his recovery from wounds and shell shock was due in no small part to his relationship with his former Sergeant, Mervyn Bunter.

Just as on the printed page, TV crime series have more Detective Inspectors than you can shake a retractable police baton at. The first to make it into my selection is, perhaps, not so well known to the general reading public, but a firm favourite with those of us who kid ourselves that we are connoisseurs. Charlie Resnick is a creation of that most cerebral of crime novelists, John Harvey. He is distinctly downbeat and his ‘patch’ is the resolutely unfashionable midlands town of Nottingham. There were eleven novels featuring the jazz loving detective, but only two of them were televised. Lonely Hearts screened in three parts in 1992, while Rough Treatment had two parts, and was broadcast a year later. Both screenplays were written by John Harvey himelf, and Tom Wilkinson brought a lonely and troubled complexity to the main role.

Just as on the printed page, TV crime series have more Detective Inspectors than you can shake a retractable police baton at. The first to make it into my selection is, perhaps, not so well known to the general reading public, but a firm favourite with those of us who kid ourselves that we are connoisseurs. Charlie Resnick is a creation of that most cerebral of crime novelists, John Harvey. He is distinctly downbeat and his ‘patch’ is the resolutely unfashionable midlands town of Nottingham. There were eleven novels featuring the jazz loving detective, but only two of them were televised. Lonely Hearts screened in three parts in 1992, while Rough Treatment had two parts, and was broadcast a year later. Both screenplays were written by John Harvey himelf, and Tom Wilkinson brought a lonely and troubled complexity to the main role.

Van der Valk took us to Amsterdam for an impressive five series, based on the novels by Nicolas Freeling. Freeling tired of his creation, and killed him off after eleven novels. He resisted the clamour to resurrect him, but did write two more books featuring the late cop’s widow. The TV series was, by way of contrast, milked for all it was worth, and Barry Foster played Commissaris Piet van der Valk against authentic Dutch settings. Amsterdam’s reputation for sleaze, sex and substances did the series no harm at all in the eyes of British sofa-dwellers. Theme tunes are an integral part of any successful series and Eye Level took on a life of its own, improbably reaching No. 1 in the British pop charts in 1973. Noel Edmunds’ barnet is irresistible, is it not?https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvesdlGe-EI

Van der Valk took us to Amsterdam for an impressive five series, based on the novels by Nicolas Freeling. Freeling tired of his creation, and killed him off after eleven novels. He resisted the clamour to resurrect him, but did write two more books featuring the late cop’s widow. The TV series was, by way of contrast, milked for all it was worth, and Barry Foster played Commissaris Piet van der Valk against authentic Dutch settings. Amsterdam’s reputation for sleaze, sex and substances did the series no harm at all in the eyes of British sofa-dwellers. Theme tunes are an integral part of any successful series and Eye Level took on a life of its own, improbably reaching No. 1 in the British pop charts in 1973. Noel Edmunds’ barnet is irresistible, is it not?https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvesdlGe-EI

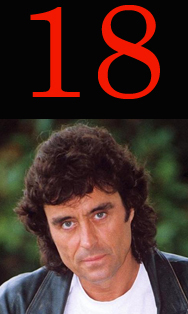

Most of my TV detectives are upright beings, not to say moral and public spirited. The East Anglian antique dealer Lovejoy was, by contrast, one of life’s chancers and, to borrow a phrase much used by local newspapers when some petty criminal has met a bad end, ‘a lovable rogue.’ Ian McShane and his impeccable mullet brought much joy to British homes on many a Sunday evening between 1986 and 1994. Lovejoy was always out for a quick quid, but like an Arthur Daley with a conscience, he always had an eye out for ‘the little guy’. McShane was excellent, but he had brilliant back-up in the persons of Phyllis Logan as the ‘did-they-didn’t-they’ posh totty Lady Jane Felsham, and the incomparable and much missed Dudley Sutton as Tinker Dill.

Most of my TV detectives are upright beings, not to say moral and public spirited. The East Anglian antique dealer Lovejoy was, by contrast, one of life’s chancers and, to borrow a phrase much used by local newspapers when some petty criminal has met a bad end, ‘a lovable rogue.’ Ian McShane and his impeccable mullet brought much joy to British homes on many a Sunday evening between 1986 and 1994. Lovejoy was always out for a quick quid, but like an Arthur Daley with a conscience, he always had an eye out for ‘the little guy’. McShane was excellent, but he had brilliant back-up in the persons of Phyllis Logan as the ‘did-they-didn’t-they’ posh totty Lady Jane Felsham, and the incomparable and much missed Dudley Sutton as Tinker Dill.

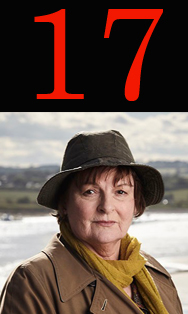

The TV version of the Vera books by Ann Cleeves is now into its quite astonishing tenth series and the demand for stories has long since outstripped the original novels. Close-to-retirement Northumbrian copper Vera Stanhope is still played by Brenda Blethyn, but her fictional police colleagues – as well as the screenwriters – have seen wholesale changes since it first aired in 2011. Why does the series do so well? Speaking cynically, there are several important contemporary boxes that it ticks. Principally, its star is a woman and it is set in the paradoxically fashionable North of England.The potential for scenic atmosphere is limitless, of course, but the core reason for its enduring popularity is the superb acting of Blethyn, and the fact that Cleeves has put together a toolkit of very clever and marketable elements. Vera will probably outlast me, and a new series is already commissioned for 2021.

The TV version of the Vera books by Ann Cleeves is now into its quite astonishing tenth series and the demand for stories has long since outstripped the original novels. Close-to-retirement Northumbrian copper Vera Stanhope is still played by Brenda Blethyn, but her fictional police colleagues – as well as the screenwriters – have seen wholesale changes since it first aired in 2011. Why does the series do so well? Speaking cynically, there are several important contemporary boxes that it ticks. Principally, its star is a woman and it is set in the paradoxically fashionable North of England.The potential for scenic atmosphere is limitless, of course, but the core reason for its enduring popularity is the superb acting of Blethyn, and the fact that Cleeves has put together a toolkit of very clever and marketable elements. Vera will probably outlast me, and a new series is already commissioned for 2021.

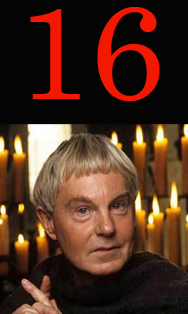

The creation of Cadfael was an act of pure genius by scholar and linguist Edith Pargetter, better known as Ellis Peters. Not only was the 12th century sleuth a devout Benedictine monk, but he had come to the cloisters only after a career as a soldier, sailor and – with a brilliant twist – a lover, as we learned that he has a son, conceived while he was fighting as a Crusader in Antioch. In the TV series which ran from 1994 until 1998, Derek Jacobi brought to the screen a superb blend of inquisitiveness, saintliness and a worldly wisdom which his fellow monks lacked, due to their entering the monastery before they had lived any kind of life. Modern times prevented the productions from being filmed in Cadfael’s native Shropshire, and they opted instead for Hungary!

The creation of Cadfael was an act of pure genius by scholar and linguist Edith Pargetter, better known as Ellis Peters. Not only was the 12th century sleuth a devout Benedictine monk, but he had come to the cloisters only after a career as a soldier, sailor and – with a brilliant twist – a lover, as we learned that he has a son, conceived while he was fighting as a Crusader in Antioch. In the TV series which ran from 1994 until 1998, Derek Jacobi brought to the screen a superb blend of inquisitiveness, saintliness and a worldly wisdom which his fellow monks lacked, due to their entering the monastery before they had lived any kind of life. Modern times prevented the productions from being filmed in Cadfael’s native Shropshire, and they opted instead for Hungary!

When my next series choice was aired in 1977, the producers had no confidence that either the name of its author, or that of its central character, would be a crowd puller, and so they called it Murder Most English. The four-part series consisted of adaptations of novels written by Colin Watson, and in print they were part of his Flaxborough Chronicles, twelve novels in total. Inspector Purbright, played by Anton Rodgers, is an apparently placid small town policeman, but a man who sees more than he says, and someone who has a sharp eye for the corruption and scheming endemic among the councillors and prominent citizens of Flaxborough – a fictional town loosely based on Boston, Lincolnshire, where Watson worked as a journalist for many years. The TV Purbright was perhaps rather more Holmesian – with his pipe and tweeds – than Watson had intended, but the original novels Hopjoy Was Here, Lonelyheart 4122, The Flaxborough Crab and Coffin Scarcely Used, were lovingly treated. Unusually, for a TV production, the filming was done in a location not too far from the fictional Flaxborough – the Lincolnshire market town of Alford, just 25 miles from Watson’s Boston workplace. Click this link to learn more about Colin Watson and his books.

When my next series choice was aired in 1977, the producers had no confidence that either the name of its author, or that of its central character, would be a crowd puller, and so they called it Murder Most English. The four-part series consisted of adaptations of novels written by Colin Watson, and in print they were part of his Flaxborough Chronicles, twelve novels in total. Inspector Purbright, played by Anton Rodgers, is an apparently placid small town policeman, but a man who sees more than he says, and someone who has a sharp eye for the corruption and scheming endemic among the councillors and prominent citizens of Flaxborough – a fictional town loosely based on Boston, Lincolnshire, where Watson worked as a journalist for many years. The TV Purbright was perhaps rather more Holmesian – with his pipe and tweeds – than Watson had intended, but the original novels Hopjoy Was Here, Lonelyheart 4122, The Flaxborough Crab and Coffin Scarcely Used, were lovingly treated. Unusually, for a TV production, the filming was done in a location not too far from the fictional Flaxborough – the Lincolnshire market town of Alford, just 25 miles from Watson’s Boston workplace. Click this link to learn more about Colin Watson and his books.

The next ten choices in my survey of the best TV detectives

follows soon – keep an eye out on TWITTER

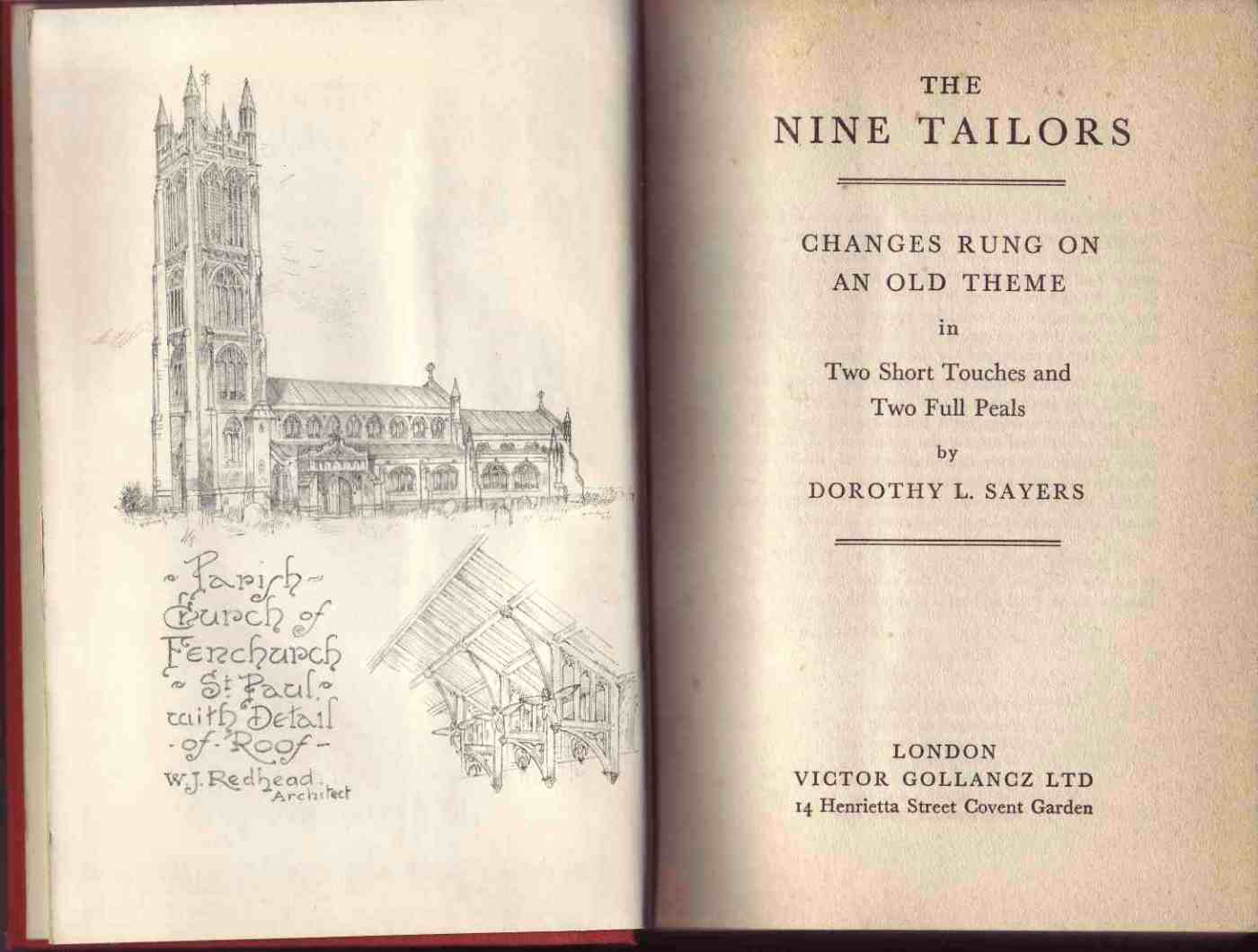

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

and a recurring – and malign – character named The Peacemaker looms over proceedings. The books work very well as detective stories, and Perry has years of experience at blending crime with period settings. She has been careful to put each plotline in the context of the big events of each year; No Graves As Yet, for example, sets us down in the elegaic final summer of peace, in an England which was still Edwardian in spirit despite the old King being four years gone; in Shoulder The Sky Reavley searches for the killer of a war correspondent whose honesty made him a marked man, and his quest for answers takes him from one military debacle to another, in this case from Ypres to Gallipoli. Perry writes with great conviction and, as with her other books, mixes intrigue, adventure, high drama and impeccable period detail.

and a recurring – and malign – character named The Peacemaker looms over proceedings. The books work very well as detective stories, and Perry has years of experience at blending crime with period settings. She has been careful to put each plotline in the context of the big events of each year; No Graves As Yet, for example, sets us down in the elegaic final summer of peace, in an England which was still Edwardian in spirit despite the old King being four years gone; in Shoulder The Sky Reavley searches for the killer of a war correspondent whose honesty made him a marked man, and his quest for answers takes him from one military debacle to another, in this case from Ypres to Gallipoli. Perry writes with great conviction and, as with her other books, mixes intrigue, adventure, high drama and impeccable period detail. The First Casualty (2005), saw stand-up comedian Ben Elton continuing a not-altogether-successful foray into the world of serious fiction. He is to be commended for placing a largely unsympathetic character at the centre of his story, but the misadventures of Douglas Kingsley, a career policeman but now a conscientious objector, tend to involve issues such as homosexuality, feminism, pacifism and the Irish Question, which were more on people’s lips at the time of Elton’s TV fame than during the period of WWI itself. Kingsley is thrown in jail because of his stance on the war, and is then abused by criminals who attribute their incarceration to his devotion to duty as a copper. The apparent murder of a rebellious soldier poet (a thinly disguised Siegfried Sassoon) and the sexual misdeeds of his wife Agnes give Kingsley plenty to think about.

The First Casualty (2005), saw stand-up comedian Ben Elton continuing a not-altogether-successful foray into the world of serious fiction. He is to be commended for placing a largely unsympathetic character at the centre of his story, but the misadventures of Douglas Kingsley, a career policeman but now a conscientious objector, tend to involve issues such as homosexuality, feminism, pacifism and the Irish Question, which were more on people’s lips at the time of Elton’s TV fame than during the period of WWI itself. Kingsley is thrown in jail because of his stance on the war, and is then abused by criminals who attribute their incarceration to his devotion to duty as a copper. The apparent murder of a rebellious soldier poet (a thinly disguised Siegfried Sassoon) and the sexual misdeeds of his wife Agnes give Kingsley plenty to think about. Rennie Airth has written a series of novels featuring a retired policeman and WWI veteran, John Madden. I am giving these an honorary mention, as Madden’s whole approach to life, his attitude towards detection, and his views on criminality are all profoundly influenced by his experience in the trenches, and when Manning is centre stage, his musings frequently recall his wartime experiences. The first of the series is River of Darkness (1999), and the events take place in 1921, when men were still dying of war wounds, and many of the country’s war memorials had still to be dedicated. Madden has returned from the war and is now a top detective with Scotland Yard. He is called down to investigate a savage multiple murder in rural Surrey, and he becomes convinced that the brutality of the killings is linked to events that happened during the war, and that the perpetrator, like Madden himself, has been left with scars that are both physical and mental. You might like to read the Fully Booked review of a later John Madden novel,

Rennie Airth has written a series of novels featuring a retired policeman and WWI veteran, John Madden. I am giving these an honorary mention, as Madden’s whole approach to life, his attitude towards detection, and his views on criminality are all profoundly influenced by his experience in the trenches, and when Manning is centre stage, his musings frequently recall his wartime experiences. The first of the series is River of Darkness (1999), and the events take place in 1921, when men were still dying of war wounds, and many of the country’s war memorials had still to be dedicated. Madden has returned from the war and is now a top detective with Scotland Yard. He is called down to investigate a savage multiple murder in rural Surrey, and he becomes convinced that the brutality of the killings is linked to events that happened during the war, and that the perpetrator, like Madden himself, has been left with scars that are both physical and mental. You might like to read the Fully Booked review of a later John Madden novel,  Bess Crawford, who manages to combine the grim task of being a nurse tending to the appalling violence inflicted upon the bodies of young men fighting in the trenches, with a determination to get to the bottom of various mysteries which have more to do with individual human failings than with the inexorable mincing machine of the war. Her investigations are sometimes within sound of German guns, but also nearer home, such as in An Unwilling Accomplice (2014), when she has to accompany a celebrity wounded soldier to Buckingham Palace to receive a gallantry award, only to have him escape his wheelchair and commit a savage murder. The Todds have also invested time and words to bring to life the character of Detective Inspector Ian Rutledge, a man who suspended his police career to fight for King and Country. He returns to the police force after the war, but finds that the blood-soaked years have left a bitter legacy, such as in A Lonely Death (2011), when he is called to investigate a series of killings in a Sussex village, and finds that the deaths are all connected with the wartime service of the victims.

Bess Crawford, who manages to combine the grim task of being a nurse tending to the appalling violence inflicted upon the bodies of young men fighting in the trenches, with a determination to get to the bottom of various mysteries which have more to do with individual human failings than with the inexorable mincing machine of the war. Her investigations are sometimes within sound of German guns, but also nearer home, such as in An Unwilling Accomplice (2014), when she has to accompany a celebrity wounded soldier to Buckingham Palace to receive a gallantry award, only to have him escape his wheelchair and commit a savage murder. The Todds have also invested time and words to bring to life the character of Detective Inspector Ian Rutledge, a man who suspended his police career to fight for King and Country. He returns to the police force after the war, but finds that the blood-soaked years have left a bitter legacy, such as in A Lonely Death (2011), when he is called to investigate a series of killings in a Sussex village, and finds that the deaths are all connected with the wartime service of the victims. I’ll conclude this first part of the feature with a quick glimpse at a trio of curiosities, where the novel gives a fleeting but significant nod to The Great War. In 1917, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published a collection of Holmes stories dating back across the first years of the century. In the concluding story His Last Bow: an epilogue of Sherlock Holmes, the great man disposes of a particularly dastardly German spy, and as the story finishes, he says,

I’ll conclude this first part of the feature with a quick glimpse at a trio of curiosities, where the novel gives a fleeting but significant nod to The Great War. In 1917, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published a collection of Holmes stories dating back across the first years of the century. In the concluding story His Last Bow: an epilogue of Sherlock Holmes, the great man disposes of a particularly dastardly German spy, and as the story finishes, he says,

Anthony Price has written many spy thrillers tinged with elements of military history, and in Other Paths To Glory (1974) he uses abandoned German fortifications deep beneath the French countryside as the central feature of the novel, most of which is set in the present day world of international realpolitik. As the bunkers in the novel are set in the Somme region, it is highly likely that they are modeled on the astonishing engineering of The Schwaben Redoubt, near Thiepval. The Redoubt was one of the most impregnable defences on The Western front, and it cost many thousands of lives before it was finally taken. The book is the fifth in the series featuring Dr David Audley and Colonel Jack Butler,

Anthony Price has written many spy thrillers tinged with elements of military history, and in Other Paths To Glory (1974) he uses abandoned German fortifications deep beneath the French countryside as the central feature of the novel, most of which is set in the present day world of international realpolitik. As the bunkers in the novel are set in the Somme region, it is highly likely that they are modeled on the astonishing engineering of The Schwaben Redoubt, near Thiepval. The Redoubt was one of the most impregnable defences on The Western front, and it cost many thousands of lives before it was finally taken. The book is the fifth in the series featuring Dr David Audley and Colonel Jack Butler,

JIM KELLY (above) grew up in the shadow of some of the worst criminal misdeeds the country had ever experienced and, as his childhood progressed, the evil that men do was seldom far away from the Kelly family. So, he had a brutal and disadvantaged upbringing? No, far from it – just the opposite. His father Brian was a top detective in the Metropolitan Police, and his maternal grandfather, too, had a background in keeping the peace as a special constable – he actually was there on the street, as it were, in 1911, when Home Secretary Winston Churchill and others managed to turn a hunt for anarchist criminals into the expensive and bungled farce that we know as the Siege of Sidney Street.

JIM KELLY (above) grew up in the shadow of some of the worst criminal misdeeds the country had ever experienced and, as his childhood progressed, the evil that men do was seldom far away from the Kelly family. So, he had a brutal and disadvantaged upbringing? No, far from it – just the opposite. His father Brian was a top detective in the Metropolitan Police, and his maternal grandfather, too, had a background in keeping the peace as a special constable – he actually was there on the street, as it were, in 1911, when Home Secretary Winston Churchill and others managed to turn a hunt for anarchist criminals into the expensive and bungled farce that we know as the Siege of Sidney Street.