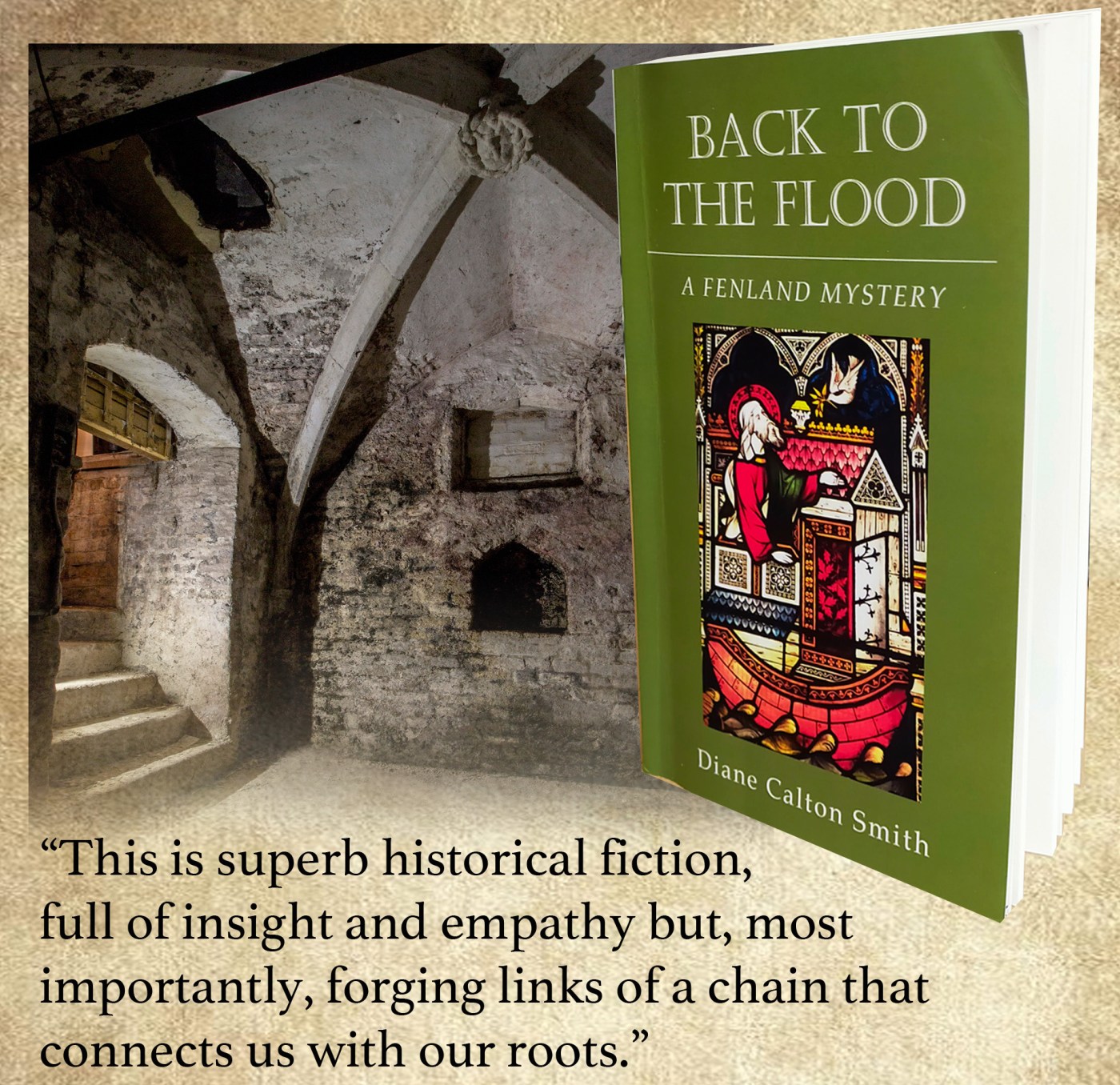

Fenland is, today, an area of Cambridgeshire and Norfolk that was once a primeval swamp, where people survived on tiny islands just high enough above the brackish water to provide shelter and sustenance. Now, the name survives as a District Council, but the waters have long since been drained and tamed. Three novelists have found the flatlands suitable for detective stories. The greatest remains Dorothy L Sayers, albeit through one book only. The Nine Tailors (1934) is a fiendishly complex murder mystery set after The Great War, although the thunderous power of barely restrained rivers is never far away. Jim Kelly’s Philip Dryden books tap in to a more sinister side of the landscape, typified by endless skies, church towers and unbroken horizons. He tells us of isolated communities, ancient jealousies and the heavy hand of history. I nominate Diane Calton Smith to complete the triumvirate. Her novels, set in Wisbech from the time of King John up to the 15th century, portray a landscape that changes little, but a social structure that has evolved.

The Principal Day, her latest,finds us in the town in 1423, with a rather splendid late medieval church (little changed today) but in a world that has changed much since the earlier novels. Local farm workers are no longer serfs and villeins, but – in the case of more skilled men – free agents who can seek employment with whoever is prepared to offer the best pay.

There is a school. Situated in a tiny room above the porch of the parish church, it is presided over by Dominus Peter Wysman, a decent enough man, but not greatly respected by one or two of his older pupils. One of the pupils, Rupert of Tilneye is a reluctant scholar, and is just days away from leaving school to go and help run his family manor at nearby Marshmeade. After several humiliations by by the teacher, he resolves to pay the man back by slipping a tiny quantity of ground up yew leaves into his drink. Yew is, of course, a deadly poison when consumed in quantity, but Rupert administers just enough to produce a violent laxative effect, much to the amusement of the scholars.

Much of the story centres on Wisbech’s Guild of The Holy Trinity, of which Peter Wysman is a member The Guilds have no modern equivalent save perhaps Freemasonry. To belong to the Guild, you had to be rich and influential, and its chief, the Alderman, was someone of great influence. They regularly dined on rich roasted meats washed down with wines imported from Europe. When, on The Principal Day (a significant day of celebration and ceremony, often centered around the feast day of the guild’s patron saint or a major religious holiday, in this case the Feast of The Holy Trinity) the Guild members gather for a lavish feast. Wysman is taken unwell, rushes outside into the Market Place, where he collapses and dies.

Rupert’s cruel prank on Wysman was widely known to the scholars. When they are questioned, Rupert is arrested for murder and thrown into the dungeons of Wisbech Castle. His mother, Lady Evelyn, is convinced that he is innocent, and travels to Ely, where she enlsists the help of Sir Henry Pelerin, the Bishop’s Seneschal. He agrees to investigate the case.

In one way, Diane Calton Smith has crafted an excellent medieval police procedural. Sir Henry Pelerin is, I suppose, the long suffering Detective Inspector, while the Constable’s Sergeant-at-arms is a bent copper worthy of modern novels. We even have a version of the stalwart of many a thriller, the brusque and abrupt police pathologist. In the end, we even have that Golden Age prerequisite, the denouement in the library. In this case, however, the principal suspects are assembled at a feast to celebrate St Thomas’s Day. If you will pardon the obvious comment, it is here that all doubt is removed from Pelerin’s mind as to who poisoned Magister Wysman.

Diane Calton Smith weaves her magic once again, and entrances us with a tale shot through with dark deeds, heartache, love and perseverance but – above all – an astonishing ability to roll away the centuries and bring the past to life. The Principal Day is published by New Generation Publishing and is available now. For more on Diane’s Wisbech books follow this link.

When Lady Frideswide is found dead beside the footpath between The Lazar House and the brewery, the Bishop’s Seneschal, Sir John Bosse is sent for and he begins his investigation. His first conclusion is that Frideswide was poisoned, by deadly hemlock being added to flask of ale, found empty and discarded on the nearby river bank. He has the method. Now he must discover means and motive. Bosse is a shrewd investigator, and he realises that Frideswide was not, by nature, a charitable woman, therefore was the valuable gift of ale a penance for a previous sin? Pondering what her crime may have been, he rules out acts of violence, as they would have been dealt with by the authorities. Robbery? Hardly, as the de Banlon family are wealthy. He has what we would call a ‘light-bulb moment’, although that metaphor is hardly appropriate for the 14th century. Frideswide, despite her unpleasant manner, was still extremely beautiful, so Bosse settles for the Seventh Commandment. But with whom did she commit adultery?

When Lady Frideswide is found dead beside the footpath between The Lazar House and the brewery, the Bishop’s Seneschal, Sir John Bosse is sent for and he begins his investigation. His first conclusion is that Frideswide was poisoned, by deadly hemlock being added to flask of ale, found empty and discarded on the nearby river bank. He has the method. Now he must discover means and motive. Bosse is a shrewd investigator, and he realises that Frideswide was not, by nature, a charitable woman, therefore was the valuable gift of ale a penance for a previous sin? Pondering what her crime may have been, he rules out acts of violence, as they would have been dealt with by the authorities. Robbery? Hardly, as the de Banlon family are wealthy. He has what we would call a ‘light-bulb moment’, although that metaphor is hardly appropriate for the 14th century. Frideswide, despite her unpleasant manner, was still extremely beautiful, so Bosse settles for the Seventh Commandment. But with whom did she commit adultery?