olitical disagreement in modern mainland Britain is largely non-violent, with the dishonorable exceptions of Islamic extremists and – further back – Irish Republican terror. For sure, tempers fray, abuse is hurled and fists are shaken. Just occasionally an egg, or maybe a milkshake, is thrown. You mightn’t think it, given the paroxysms of fury displayed on social media, but sticks and stones are rarely seen. Scottish writer SG MacLean in her series featuring the Cromwellian enforcer Damian Seeker reminds us that we have a violent history.

olitical disagreement in modern mainland Britain is largely non-violent, with the dishonorable exceptions of Islamic extremists and – further back – Irish Republican terror. For sure, tempers fray, abuse is hurled and fists are shaken. Just occasionally an egg, or maybe a milkshake, is thrown. You mightn’t think it, given the paroxysms of fury displayed on social media, but sticks and stones are rarely seen. Scottish writer SG MacLean in her series featuring the Cromwellian enforcer Damian Seeker reminds us that we have a violent history.

In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector.

In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector.

In London, Damian Seeker is a formidable foe to those who yearn for the return of the monarchy. He is physically intimidating, has a fearsome reputation for violence but, like many more modern heroes, Seeker has a fragile personal life. To put Seeker into a modern fictional context, he is Jack Reacher and Harry Callaghan in breeches, stockings and with leather gauntlets on his hands. He has a primed and cocked flintlock pistol by his side, but doesn’t trust modern technology. His weapons of choice are his own fists and a brutal medieval mace.

The story begins with the chance discovery of a mutilated corpse in an outhouse south of the river, in Lambeth – the seventeenth century version of 1970s Soho. The dead man was chained and appears to have been savaged by a dog, except that dogs don’t have five razor sharp claws on each paw. Seeker has to accept the impossible truth. The man has been mauled by a bear. But hasn’t bear-baiting been banned, and haven’t the remaining beasts been removed and killed? Like other practices banned by the zealous moral guardians of Cromwell’s government, bear-baiting and dog-fighting have simply – to use a totally anachronistic metaphor – slipped beneath the radar.

hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history

hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history  tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

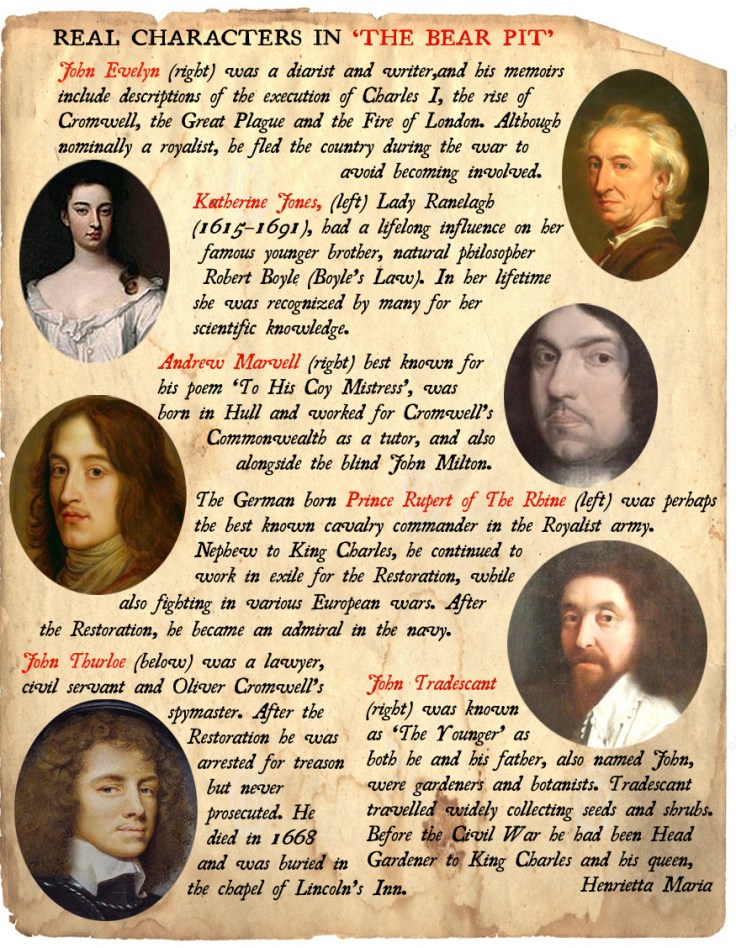

McLean’s research is impeccable. She provides us with a clutch of recognisable real-life characters, and even the desperadoes who do their best to kill Cromwell are actual historical figures. She allows herself the luxury of a little what-iffery with the identity of the mysterious Boyes, ringleader of the plot, but this is all great fun and you would have to be a dull old thing not to be carried along with this excellent historical adventure.

The Bear Pit is published by Quercus and is out now. The Fully Booked review of the precious Damien Seeker novel, The Black Friar, is here.

Shona MacLean opens the door of her time machine and takes us to the city of London in the third year of Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate, 1655. It is almost exactly six years since the severed head of King Charles was shown to the crowd around the scaffold in Whitehall, but Cromwell’s England is still a troubled place. There are still pockets of secret Royalist sympathy up and down the land, and the dead king’s son is in exile, waiting his moment to return.

Shona MacLean opens the door of her time machine and takes us to the city of London in the third year of Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate, 1655. It is almost exactly six years since the severed head of King Charles was shown to the crowd around the scaffold in Whitehall, but Cromwell’s England is still a troubled place. There are still pockets of secret Royalist sympathy up and down the land, and the dead king’s son is in exile, waiting his moment to return. MacLean (right) has great fun with prominent real-life characters who would certainly have been involved in affairs of state at the time. We have a nicely imagined Andrew Marvell, the poet best known for his erotic supplication To His Coy Mistress, and a walk on part for Samuel Pepys. The great diarist is merely a clerk at The Exchequer, but his later reputation as a serial seducer of young women is hinted at. We see the spymaster John Thurloe apparently at death’s door with some unspecified illness, but in real life he was to survive the restoration of the monarchy, and died peacefully in his bed in 1668.

MacLean (right) has great fun with prominent real-life characters who would certainly have been involved in affairs of state at the time. We have a nicely imagined Andrew Marvell, the poet best known for his erotic supplication To His Coy Mistress, and a walk on part for Samuel Pepys. The great diarist is merely a clerk at The Exchequer, but his later reputation as a serial seducer of young women is hinted at. We see the spymaster John Thurloe apparently at death’s door with some unspecified illness, but in real life he was to survive the restoration of the monarchy, and died peacefully in his bed in 1668.