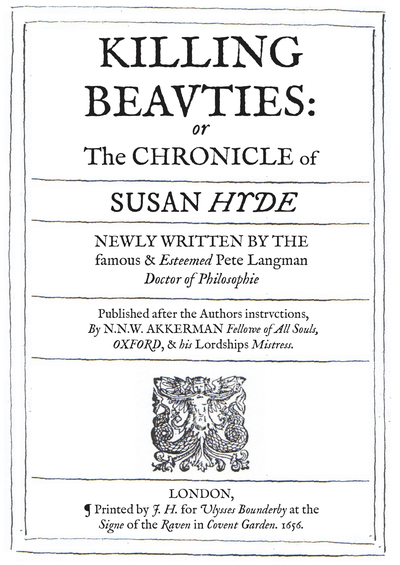

The idea of the female spy has attracted writers and dramatists over the years with its unbeatable combination of danger and sexual allure. Pete Langman comes to the party with his enjoyable new novel, Killing Beauties set in the England of 1655. Remember those old historical movies that began with a dramatic piece of text scrolling over the opening titles, giving us a lurid and enticing potted background to whatever we were about to watch? The blurb for Killing Beauties might say something like, “England’s King Charles is six years dead and the brutal tyrant Oliver Cromwell rules the land with an iron fist, aided by his evil spymaster John Thurloe. While the dead King’s son waits impatiently across the English Channel, a beautiful woman plots the downfall of Cromwell’s savage regime.”

The idea of the female spy has attracted writers and dramatists over the years with its unbeatable combination of danger and sexual allure. Pete Langman comes to the party with his enjoyable new novel, Killing Beauties set in the England of 1655. Remember those old historical movies that began with a dramatic piece of text scrolling over the opening titles, giving us a lurid and enticing potted background to whatever we were about to watch? The blurb for Killing Beauties might say something like, “England’s King Charles is six years dead and the brutal tyrant Oliver Cromwell rules the land with an iron fist, aided by his evil spymaster John Thurloe. While the dead King’s son waits impatiently across the English Channel, a beautiful woman plots the downfall of Cromwell’s savage regime.”

he beautiful woman is Susan Hyde, whose brother Sir Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon is principle advisor to the King in exile. With the aid of another young woman, Diane Jennings, Susan – and other members of the secret society known as Les Filles d’Ophelie – work with The Sealed Knot, coordinating underground Royalist activity in England and preparing for a general uprising against the Protectorate. Readers may be aware that the modern version of The Sealed Knot is a popular organisation of English Civil War re-enactors, but their historical namesakes were in deadly earnest, and organised two major rebellions before Charles II was finally crowned in 1661.

he beautiful woman is Susan Hyde, whose brother Sir Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon is principle advisor to the King in exile. With the aid of another young woman, Diane Jennings, Susan – and other members of the secret society known as Les Filles d’Ophelie – work with The Sealed Knot, coordinating underground Royalist activity in England and preparing for a general uprising against the Protectorate. Readers may be aware that the modern version of The Sealed Knot is a popular organisation of English Civil War re-enactors, but their historical namesakes were in deadly earnest, and organised two major rebellions before Charles II was finally crowned in 1661.

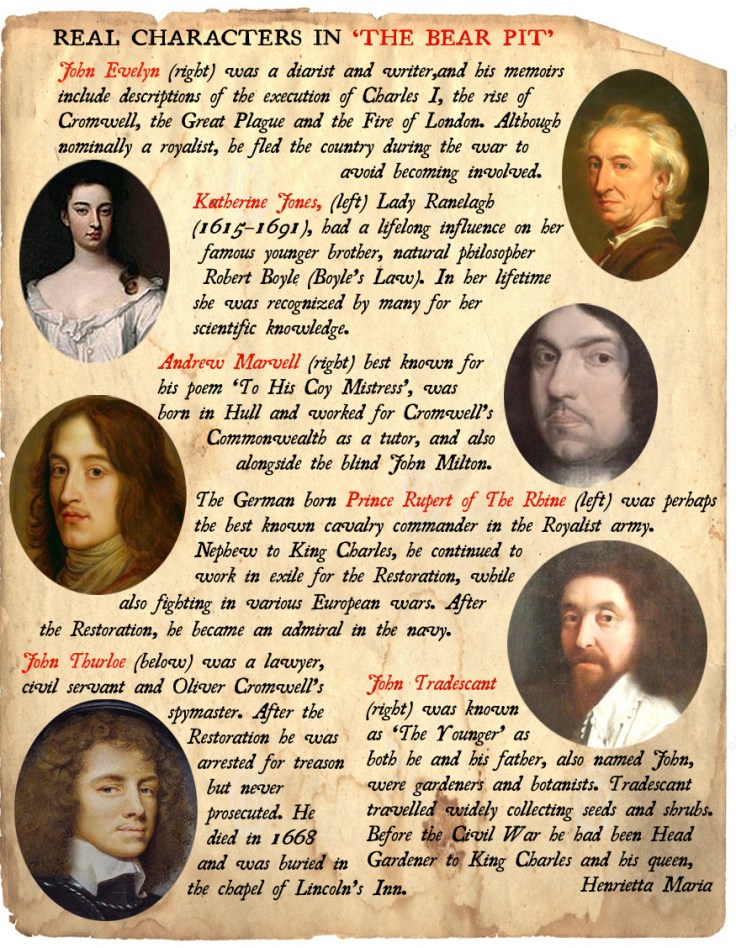

In order to succeed in her mission, Susan must use the deadliest weapon at her disposal – her sexuality. The beneficiary of her attention is none other than John Thurloe himself. Thurloe is a fascinating historical figure, and has featured in several other novels, most notably in the Thomas Challoner series by Susanna Gregory, and in the SG MacLean’s Seeker stories. I reviewed MacLean’s The Bear Pit and The Black Friar, and you can click the links to go to the reviews.

In order to succeed in her mission, Susan must use the deadliest weapon at her disposal – her sexuality. The beneficiary of her attention is none other than John Thurloe himself. Thurloe is a fascinating historical figure, and has featured in several other novels, most notably in the Thomas Challoner series by Susanna Gregory, and in the SG MacLean’s Seeker stories. I reviewed MacLean’s The Bear Pit and The Black Friar, and you can click the links to go to the reviews.

Killing Beauties, as you might expect, gives us much general skullduggery, swordplay, concealing messages in all kinds of unlikely places, fatal potions (one swallowed, memorably, by an unfortunate goat) and hearts beating with passion beneath many a female bodice. Langman writes with great energy, and his style reminds me rather of a long forgotten historical novelist whose books I still read from time to time – Jeffery Farnol. Farnol, however was much too delicate – or perhaps his readers were – to revel in the stink and squalor of the time. Langman has no such qualms:

“Walking through the filthy streets of London was always a hazardous proposition for a lone woman. If she wasn’t slipping in piles of animal dung or sliding in puddles of their stale, she was avoiding the buckets of human waste that appeared from every angle …. and once this was negotiated, there was the matter of the animal life. The kicking, braying, pissing, shitting, trotting, running, flying and fleeing animal life that abounded.”

ne of the problems facing writers of historical fiction is how to handle dialogue. We know how they wrote to each other in letters, but what were conversations like? Despite one or two of his characters occasionally lapsing into more recent vernacular, Langman negotiates this particular minefield successfully. Killing Beauties is an engaging and well researched piece of costume drama acted out on a turbulent and dangerous stage. It is published by Unbound and is out now.

ne of the problems facing writers of historical fiction is how to handle dialogue. We know how they wrote to each other in letters, but what were conversations like? Despite one or two of his characters occasionally lapsing into more recent vernacular, Langman negotiates this particular minefield successfully. Killing Beauties is an engaging and well researched piece of costume drama acted out on a turbulent and dangerous stage. It is published by Unbound and is out now.

olitical disagreement in modern mainland Britain is largely non-violent, with the dishonorable exceptions of Islamic extremists and – further back – Irish Republican terror. For sure, tempers fray, abuse is hurled and fists are shaken. Just occasionally an egg, or maybe a milkshake, is thrown. You mightn’t think it, given the paroxysms of fury displayed on social media, but sticks and stones are rarely seen. Scottish writer SG MacLean in her series featuring the Cromwellian enforcer Damian Seeker reminds us that we have a violent history.

olitical disagreement in modern mainland Britain is largely non-violent, with the dishonorable exceptions of Islamic extremists and – further back – Irish Republican terror. For sure, tempers fray, abuse is hurled and fists are shaken. Just occasionally an egg, or maybe a milkshake, is thrown. You mightn’t think it, given the paroxysms of fury displayed on social media, but sticks and stones are rarely seen. Scottish writer SG MacLean in her series featuring the Cromwellian enforcer Damian Seeker reminds us that we have a violent history. In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector.

In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector. hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history

hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history  tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.