In Helen Steadman’s Solstice (click to read the review) she showed us the astonishing capacity for malice that lurked in the hearts of some Puritan Christians. In The Running Wolf, set slightly later in time, sectarian divisions are more in the background as she draws us into a Britain in the late years of the 17th century and the first decades of the 18th century. In 1688, when the Catholic King James II was replaced by the hastily imported Protestant William of Orange, the sectarian divide was not healed, but merely temporarily bridged.

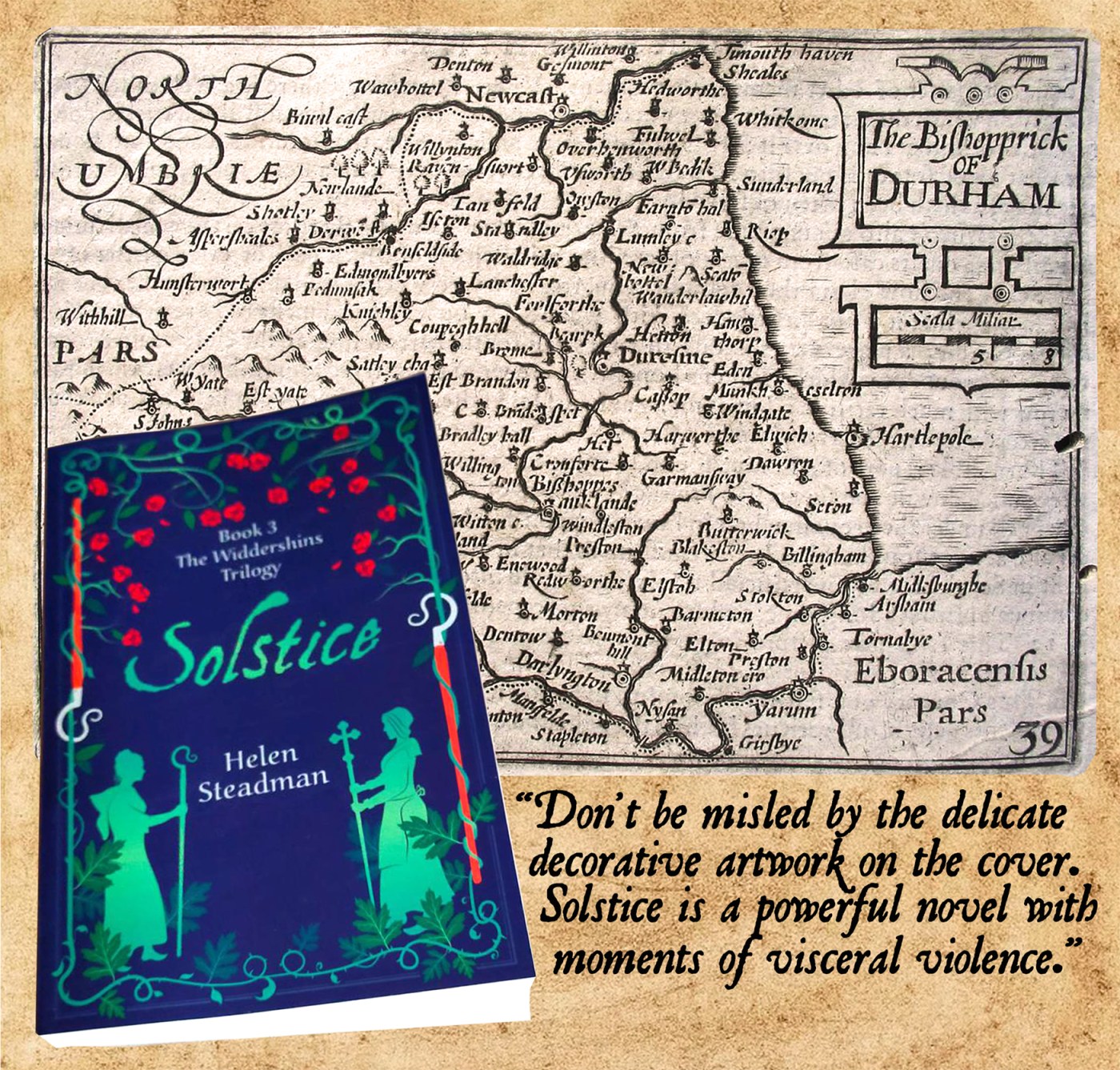

Central to the story is an unusual migration – that of sword makers, based in the German town of Solingen who, in 1688, moved, lock stock and barrel, to the tiny settlement of Shotley Bridge in County Durham. The reason for their move was basically economic. Solingen was almost literally bursting at the seams with sword makers, and work was becoming increasingly hard to come by. The departing craftsmen and their families, however, faced the wrath of the exclusive town guilds – to whom they had sworn an oath never to reveal the crucial secret techniques which made a Solingen sword one of the best in the world.

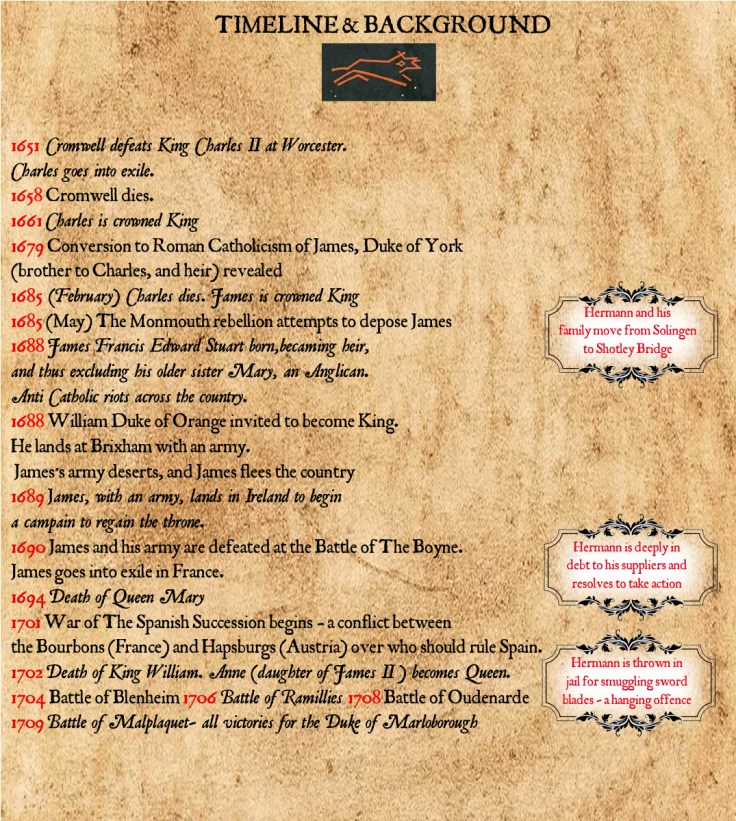

Hermann Molle (who actually existed) makes the journey, with his family, to Shotley Bridge, and slowly builds his business again. As Lutherans they are, to an extent, on the right side of the ‘Protestant Angels’, but the supporters – the Jacobites – of the exiled King James are growing in strength and, particularly across the English Channel, their numbers begin to pose a significant threat. Check this historical timeline:

We watch as Hermann, his family – and the other German exiles – gradually rebuild their lives in Shotley Bridge, integrating as necessary, but preserving their own culture and customs. Their swords are, initially much sought after, but as the century draws to a close the craftsmen begin to feel the winds of change. While some men of wealth are still prepared to pay for a well made sword, the blades are beginning to be valued more for ornamental use than as lethal weapons, and the smiths of the future will have to turn their hands to fashioning gun barrels rather than cutting edges.

The men of Shotley Bridge have another problem – what we would nowadays call cash flow. Customers are not paying their bills, but the dealers who provide the raw material insist on being paid in full and on time. Hermann takes a risk, returns to Solingen and attempts to smuggle a consignment of German blades back into England. He is caught, and thrown into Morpeth gaol, with every expectation that he will be hanged for his pains.

Helen Steadman tells a gripping story, using the twin timelines of the Germans establishing their craft alongside the River Derwent and, using a corrupt gaoler as narrator, Hermann’s time of misery as he languishes in the squalor of his prison cell. There is fascinating detail about the craft of sword making, set against the rumbling of military and political events far away, but equally mesmerising is the way Helen Steadman captures the minutiae of the daily lives of Hermann and his family. This is historical fiction of the first order. The Running Wolf is published by Impress Books and is available now.

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as