The book begins with a terrific passage:

“The child looked like a porcelain doll. Dark eyelashes resting on pale cheeks, softly pouting lips, sandy hair swept neatly under a flat brown cap. Delicate hands folded across a miniature cotton shirt and waistcoat. A figure of peace, placed in repose on the bracken as if simply lying down to rest next to a pyramid of rocks. Even the bluish tinge to the skin could have explained away by the moonlight.“

Sarah Sultoon is not the first writer to exploit the dank mysteries of the Essex marshes. In Bleak House, Dickens used the perennial swirling mist and sense of despair as a metaphor for the obfuscations and terminal lack of transparency which enmesh Jarndyce v Jarndyce. The River Blackwater exists. It rises in rural Essex and expands into a considerable estuary, but the island in this novel is pure fiction.

On starting the novel I wondered how someone could sustain a thriller billed to be about the fabled Millennium Bug – something that never actually happened. I should have had more faith. The discovery of a dead child on Blackwater Island is only briefly mentioned on the news as the world waits for computer systems to shut down, and passenger jets to tumble from the sky, but journalist Jonny Murphy is sent down to Essex to investigate. What he finds is truly astonishing.

Deeply embedded in the mystery is Murphy, aided and abetted by his American ‘not quite’ girlfriend Paloma. He is certainly fearless, but I was reminded of those female characters in Hammer horror films, who decide to go and investigate the ruined church at midnight, dressed in a negligee, and armed only with a flickering candle. Despite our cries of ‘Don’t go there!’ she does, as does Johnny.

This is indeed a weird and wonderful fantasy. The closest comparison I can come up with may only chime with readers who share my my advanced years, but Blackwater is rather reminiscent of the African tales of H Rider Haggard. I suspect no-one reads him these days, but back in the day his fantastical tales of adventure were very popular. Essex is a long way from darkest Africa, but Sarah Sultoon emulates Haggard by creating a cast of intriguingly odd characters. Instead of Gagool, the malevolent witch in King Solomon’s Mines, we have Judith, the strange landlady of The Saxon: Haggard gave us the imposing Ayesha in She, (as in She Who Must Be Obeyed) but here we have ‘Jane’, the Amazonian former special forces trooper who lurks on the island. Sultoon then decides to go for broke and throw into the mix triplets, a grief-stricken recluse and an emaciated druid.

Aside from the goings-on in the riverside hamlet of Eastwood, where Judith’s pub serves only plates of local oysters and glasses of a locally concocted spirit consisting mainly of ethanol, there is a serious background which revolves round biological warfare and the way governments across the world will lie to the people who elected it, all in the name of ‘national interest’. Despite the improbable storyline, Blackwater is immensely entertaining, and I read it over a couple of enjoyable evenings. It is published by Orenda Books and is available now.

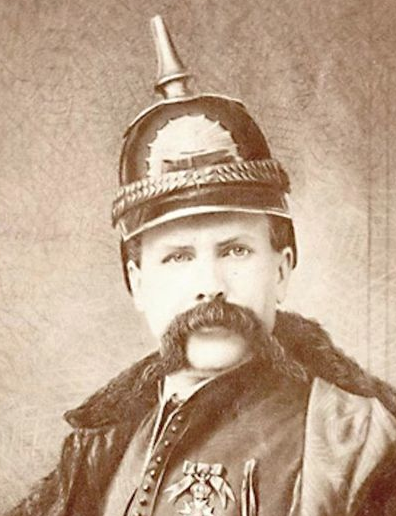

Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence.

Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence. Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

That, then, is the Aliens moment. Events move with terrifying speed. Mackenzie is airlifted back to England and isolation and the wheels of government and the intelligence agencies begin to whirr. Given that there is a large Russian presence in Svalbard, ostensibly for mining operations, the fingers of guilt begin to point towards Moscow, particularly when the virus is found to be man-made.

That, then, is the Aliens moment. Events move with terrifying speed. Mackenzie is airlifted back to England and isolation and the wheels of government and the intelligence agencies begin to whirr. Given that there is a large Russian presence in Svalbard, ostensibly for mining operations, the fingers of guilt begin to point towards Moscow, particularly when the virus is found to be man-made.