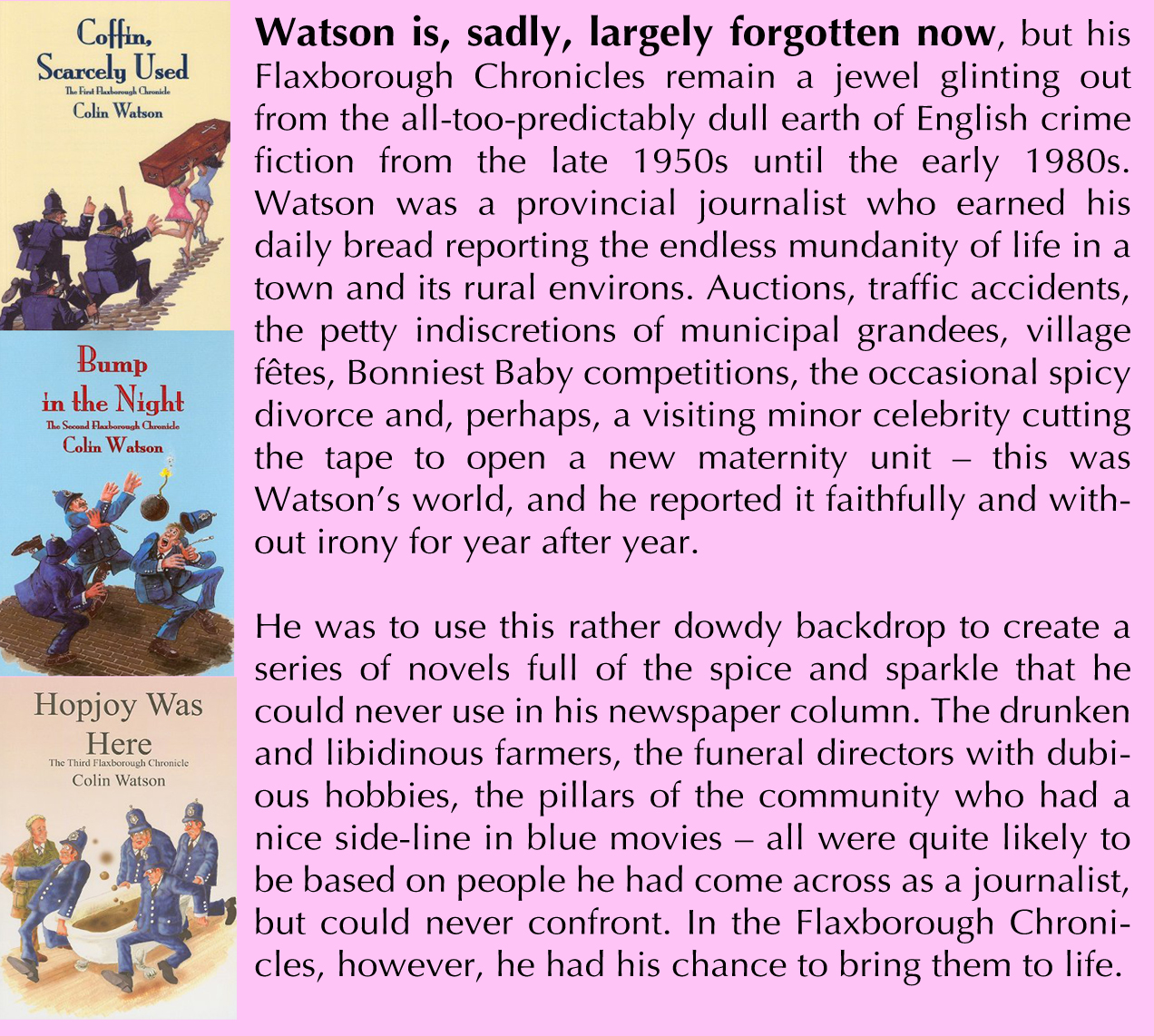

It is a sad reflection on modern tastes in crime fiction – and marketing – that, although his books are still in print, if you click on the author bio bit of the Amazon page for Colin Watson’s Blue Murder, there is nothing there. Truth is, by the time the book was published, in 1979, Watson had all but given up writing as a bad job. There were just two books in his Flaxborough series to come before his death in 1983. After a lifetime in provincial journalism, he had retired to he “the Lincolnshire village of Folkingham, where he spent most of his time engrossed in his hobby as a silversmith. You can read more about his career as a writer here.

The book opens with a long – but wonderful – paragraph describing the fictional town of Flaxborough. It has little to do with the plot of Blue Murder, but it is a shining an example of Watson’s skill as a writer, and I make no apologies for quoting it in its entirety.

“Friday was market day in Flaxborough. It was a somewhat tenuous survival, perhaps, but not yet an anachronism. Long departed, certainly, were the little wheeled huts – not unlike Victorian bathing machines – in which corn and seed chandlers shook samples from small canvas bags into the palms of farmers, each the size of a malt shovel, and invited them to “give it a nose:, whereupon the farmer would inaugurate the long and infinitely casual process of making a deal by observing unrancorously that he’d seen better wheat dug out of middens. Nor were animals any longer part of the market day scene. The iron railings and corridors; the weighbridge;, the show ring, pooled with the pungent staling of bullocks and stained here and bear with dried-off urine that looked like lemonade powder; the raised, half round, open pavilion with a clock tower on top, where the auctioneers impassively interpreted twitches, nods and glances from the stone faced butchers and dealers: all these had disappeared from the market place. So, too, had the drovers, those wondrously misshapen but agile men, who hopped, loped and darted among the sweating beasts and intimidated them with wrathful cries and stick waving. In the long black coat, roped around the middle, that they wore in all conditions of weather, the drovers of Flaxborough had looked like demented mediaeval clerics, bent on Benedictine and buggery.”

Watson (pictured) spent years working for provincial newspapers, writing up endless articles on civic functions, what passed for ‘society’ weddings, bickering councillors, glimpses of local scandals, and petty offenders appearing before bibulous local magistrates. This gave him a unique insight into what made small-town England tick. He could be acerbic, but never vicious. he usually found space to write about fictional versions of himself – local journalists. In this case, a Mr Kebble, editor of the local rag.

Watson (pictured) spent years working for provincial newspapers, writing up endless articles on civic functions, what passed for ‘society’ weddings, bickering councillors, glimpses of local scandals, and petty offenders appearing before bibulous local magistrates. This gave him a unique insight into what made small-town England tick. He could be acerbic, but never vicious. he usually found space to write about fictional versions of himself – local journalists. In this case, a Mr Kebble, editor of the local rag.

“Mr Kebble rode a cycle with as much panache as a squire might ride his hunter. Instead of field gear, though, he wore his unvarying costume of leather elbowed tweed jacket, trousers like twin bags of oatmeal and the editorial waistcoat whose host of pockets accommodated useful equipment that ranged from a portable balance for weighing fish to a goldsmiths touchstone. His hat, a carefully preserved relic of journalism in the twenties, was stiff, creamy–grey felt, high-crowned and broad of brim, which perched far back on his head to give full display to the round, pink, mischievously amiable face.”

In a strange way, the plot of Blue Murder is neither here nor there, as it is merely a vehicle for Watson’s beguiling way with words. It features – as do all the Flaxborough novels – the imperturbable Inspector Walter Purbright, a man benign in appearance and manner, but possessed of a sharp intelligence and an ability to spot deception and dissembling at a hundred yards distance. Long story short, a red-top national newspaper, The Herald, has been tipped off that the redoubtable burghers of Flaxborough are implicated in a blue movie, what used to be known as a stag film. On arriving in Flaxborough, the investigating team, headed by muck-raker in chief Clive Grail, assisted by his delightful PA, Miss Birdie Clemenceaux. manage to fall foul of the combative town Mayor, Charlie Hocksley. Hocksley has his finger in more local pies than the town baker can turn out, for example:

In a strange way, the plot of Blue Murder is neither here nor there, as it is merely a vehicle for Watson’s beguiling way with words. It features – as do all the Flaxborough novels – the imperturbable Inspector Walter Purbright, a man benign in appearance and manner, but possessed of a sharp intelligence and an ability to spot deception and dissembling at a hundred yards distance. Long story short, a red-top national newspaper, The Herald, has been tipped off that the redoubtable burghers of Flaxborough are implicated in a blue movie, what used to be known as a stag film. On arriving in Flaxborough, the investigating team, headed by muck-raker in chief Clive Grail, assisted by his delightful PA, Miss Birdie Clemenceaux. manage to fall foul of the combative town Mayor, Charlie Hocksley. Hocksley has his finger in more local pies than the town baker can turn out, for example:

“He was also a leading member of one of those bands of emigré Scotsman who gather once a year in every English town to mourn, in whisky, sheep-gut and oatmeal, their sufferance of prosperity in exile.”

The blue movie is screened to the visiting journalists, projected onto the obligatory bed sheet pinned to the wall. Bizarrely, the soundtrack is in Arabic but, fear not, a translator called Mr Suffri is at hand, and he enlivens the visuals with his work:

“The gentleman says he intends to pulverise the lady in the pistol and the mortar of his lusting and she gives answer which please I wish to be excused.”

Grail and his team discover that the link between the stag film (a grotesque re-imaging of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly} and local worthies is flimsy and so, to create a story, they stage a fake kidnapping of Grail, after which the fake kidnappers demand a ransom Herald’s Australian owners have little option but to pay. Unfortunately, one of the news gatherers has a long standing wrong to avenge, and Grail is found dead. Purbright unpicks the knotted bundle of threads to expose the killer but, as I said earlier, this is all subsidiary to the main enjoyment to be taken from this little book – just 160 pages – that being Watson’s wonderful sense of the absurd, his pin sharp observations about English society, and his felicity with our language.

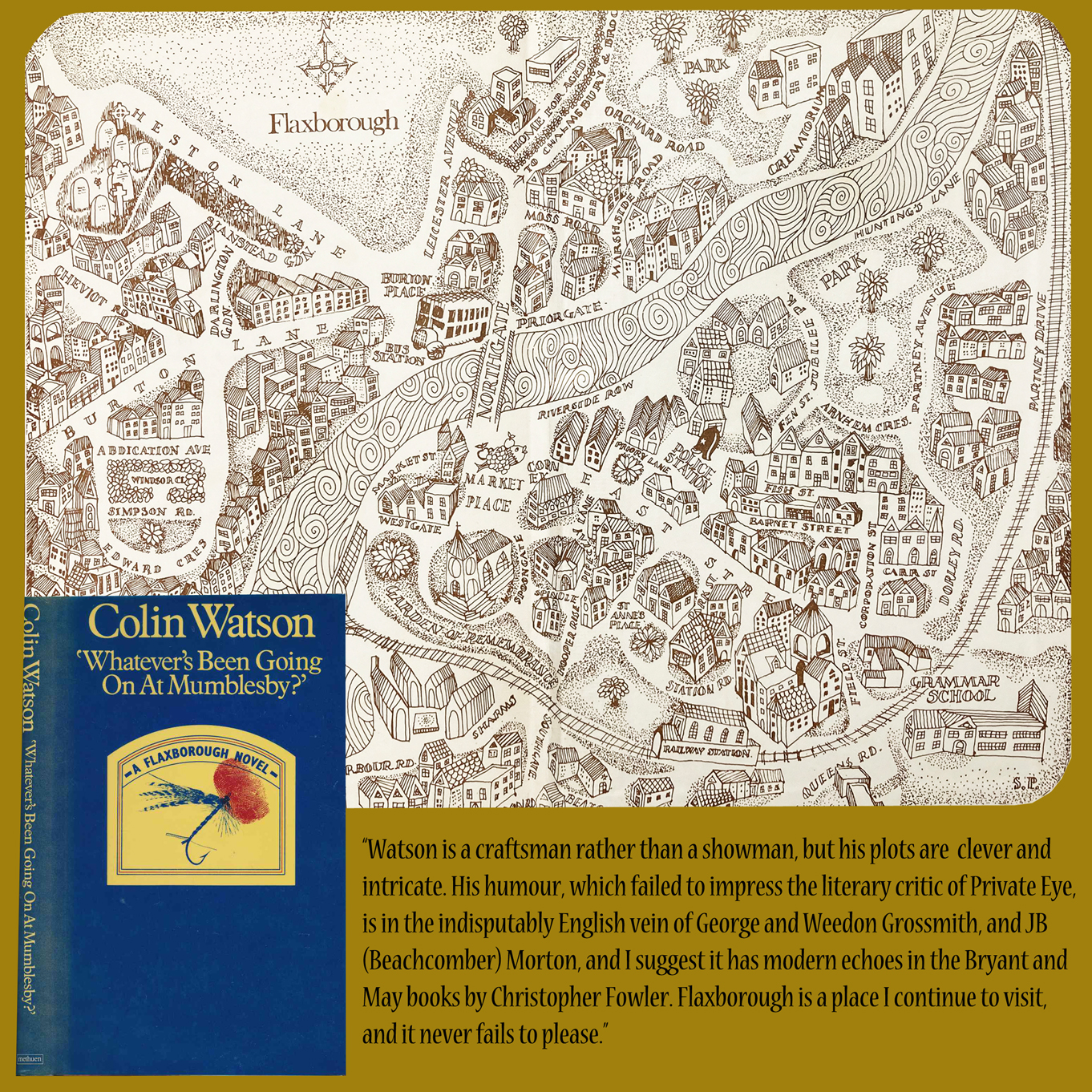

The next stage of our journey is to a town that doesn’t exist – at least on an Ordance Survey map. Writers have always created fictional towns based on real places – think Thomas Hardy’s Casterbridge, Trollope’s Barchester, Arnold Bennett’s Bursley, Herriot’s Darrowby, and Dylan Thomas’s Llareggub – but remember that each was based on a real life place well known to the writer. Thus we drive along a road that skirts the windswept and muddy shores of The Wash until we arrive in Boston, Lincolnshire. It was here that the journalist and writer Colin Watson lived and worked for many years, and it was in Boston’s image that he created Flaxborough – the home and jurisdiction of Inspector Walter Purbright.

The next stage of our journey is to a town that doesn’t exist – at least on an Ordance Survey map. Writers have always created fictional towns based on real places – think Thomas Hardy’s Casterbridge, Trollope’s Barchester, Arnold Bennett’s Bursley, Herriot’s Darrowby, and Dylan Thomas’s Llareggub – but remember that each was based on a real life place well known to the writer. Thus we drive along a road that skirts the windswept and muddy shores of The Wash until we arrive in Boston, Lincolnshire. It was here that the journalist and writer Colin Watson lived and worked for many years, and it was in Boston’s image that he created Flaxborough – the home and jurisdiction of Inspector Walter Purbright.

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

Victorian coppers were not new to TV when this Sergeant Cribb, based on the excellent Peter Lovesey novels, first aired. There had already been several attempts at the Holmes canon, and way back in 1963 John Barrie starred as Sergeant Cork. Although a serial, rather than a series, the 1959 version of The Moonstone featured the great Patrick Cargill as Sergeant Cuff, possibly the first fictional detective. Where Sergeant Cribb came to life was through the superbly dry and acerbic characterisation of Alan Dobie, aided and abetted by the ever-dependable William Simons. Neither did it hurt that most of the episodes were written by Peter Lovesey himself. (1980 – 1981)

Victorian coppers were not new to TV when this Sergeant Cribb, based on the excellent Peter Lovesey novels, first aired. There had already been several attempts at the Holmes canon, and way back in 1963 John Barrie starred as Sergeant Cork. Although a serial, rather than a series, the 1959 version of The Moonstone featured the great Patrick Cargill as Sergeant Cuff, possibly the first fictional detective. Where Sergeant Cribb came to life was through the superbly dry and acerbic characterisation of Alan Dobie, aided and abetted by the ever-dependable William Simons. Neither did it hurt that most of the episodes were written by Peter Lovesey himself. (1980 – 1981)

Small, aggressive, punchy and with hard earned bags under his eyes, Mark McManus was Taggart. Before he drank himself to death, McManus drove the Glasgow cop show, repaired its engine and polished its bodywork to perfection. It was Scottish Noir before the term had come into common parlance. Bleak, abrasive, unforgiving and with a killer theme song, Taggart was a one-off. The series limped on after McManus died but it was never the same again. (1983 – 1995)

Small, aggressive, punchy and with hard earned bags under his eyes, Mark McManus was Taggart. Before he drank himself to death, McManus drove the Glasgow cop show, repaired its engine and polished its bodywork to perfection. It was Scottish Noir before the term had come into common parlance. Bleak, abrasive, unforgiving and with a killer theme song, Taggart was a one-off. The series limped on after McManus died but it was never the same again. (1983 – 1995)

Most of my TV detectives are upright beings, not to say moral and public spirited. The East Anglian antique dealer Lovejoy was, by contrast, one of life’s chancers and, to borrow a phrase much used by local newspapers when some petty criminal has met a bad end, ‘a lovable rogue.’ Ian McShane and his impeccable mullet brought much joy to British homes on many a Sunday evening between 1986 and 1994. Lovejoy was always out for a quick quid, but like an Arthur Daley with a conscience, he always had an eye out for ‘the little guy’. McShane was excellent, but he had brilliant back-up in the persons of Phyllis Logan as the ‘did-they-didn’t-they’ posh totty Lady Jane Felsham, and the incomparable and much missed Dudley Sutton as Tinker Dill.

Most of my TV detectives are upright beings, not to say moral and public spirited. The East Anglian antique dealer Lovejoy was, by contrast, one of life’s chancers and, to borrow a phrase much used by local newspapers when some petty criminal has met a bad end, ‘a lovable rogue.’ Ian McShane and his impeccable mullet brought much joy to British homes on many a Sunday evening between 1986 and 1994. Lovejoy was always out for a quick quid, but like an Arthur Daley with a conscience, he always had an eye out for ‘the little guy’. McShane was excellent, but he had brilliant back-up in the persons of Phyllis Logan as the ‘did-they-didn’t-they’ posh totty Lady Jane Felsham, and the incomparable and much missed Dudley Sutton as Tinker Dill. The TV version of the Vera books by Ann Cleeves is now into its quite astonishing tenth series and the demand for stories has long since outstripped the original novels. Close-to-retirement Northumbrian copper Vera Stanhope is still played by Brenda Blethyn, but her fictional police colleagues – as well as the screenwriters – have seen wholesale changes since it first aired in 2011. Why does the series do so well? Speaking cynically, there are several important contemporary boxes that it ticks. Principally, its star is a woman and it is set in the paradoxically fashionable North of England.The potential for scenic atmosphere is limitless, of course, but the core reason for its enduring popularity is the superb acting of Blethyn, and the fact that Cleeves has put together a toolkit of very clever and marketable elements. Vera will probably outlast me, and a new series is already commissioned for 2021.

The TV version of the Vera books by Ann Cleeves is now into its quite astonishing tenth series and the demand for stories has long since outstripped the original novels. Close-to-retirement Northumbrian copper Vera Stanhope is still played by Brenda Blethyn, but her fictional police colleagues – as well as the screenwriters – have seen wholesale changes since it first aired in 2011. Why does the series do so well? Speaking cynically, there are several important contemporary boxes that it ticks. Principally, its star is a woman and it is set in the paradoxically fashionable North of England.The potential for scenic atmosphere is limitless, of course, but the core reason for its enduring popularity is the superb acting of Blethyn, and the fact that Cleeves has put together a toolkit of very clever and marketable elements. Vera will probably outlast me, and a new series is already commissioned for 2021. The creation of Cadfael was an act of pure genius by scholar and linguist Edith Pargetter, better known as Ellis Peters. Not only was the 12th century sleuth a devout Benedictine monk, but he had come to the cloisters only after a career as a soldier, sailor and – with a brilliant twist – a lover, as we learned that he has a son, conceived while he was fighting as a Crusader in Antioch. In the TV series which ran from 1994 until 1998, Derek Jacobi brought to the screen a superb blend of inquisitiveness, saintliness and a worldly wisdom which his fellow monks lacked, due to their entering the monastery before they had lived any kind of life. Modern times prevented the productions from being filmed in Cadfael’s native Shropshire, and they opted instead for Hungary!

The creation of Cadfael was an act of pure genius by scholar and linguist Edith Pargetter, better known as Ellis Peters. Not only was the 12th century sleuth a devout Benedictine monk, but he had come to the cloisters only after a career as a soldier, sailor and – with a brilliant twist – a lover, as we learned that he has a son, conceived while he was fighting as a Crusader in Antioch. In the TV series which ran from 1994 until 1998, Derek Jacobi brought to the screen a superb blend of inquisitiveness, saintliness and a worldly wisdom which his fellow monks lacked, due to their entering the monastery before they had lived any kind of life. Modern times prevented the productions from being filmed in Cadfael’s native Shropshire, and they opted instead for Hungary! When my next series choice was aired in 1977, the producers had no confidence that either the name of its author, or that of its central character, would be a crowd puller, and so they called it Murder Most English. The four-part series consisted of adaptations of novels written by Colin Watson, and in print they were part of his Flaxborough Chronicles, twelve novels in total. Inspector Purbright, played by Anton Rodgers, is an apparently placid small town policeman, but a man who sees more than he says, and someone who has a sharp eye for the corruption and scheming endemic among the councillors and prominent citizens of Flaxborough – a fictional town loosely based on Boston, Lincolnshire, where Watson worked as a journalist for many years. The TV Purbright was perhaps rather more Holmesian – with his pipe and tweeds – than Watson had intended, but the original novels Hopjoy Was Here, Lonelyheart 4122, The Flaxborough Crab and Coffin Scarcely Used, were lovingly treated. Unusually, for a TV production, the filming was done in a location not too far from the fictional Flaxborough – the Lincolnshire market town of Alford, just 25 miles from Watson’s Boston workplace. Click

When my next series choice was aired in 1977, the producers had no confidence that either the name of its author, or that of its central character, would be a crowd puller, and so they called it Murder Most English. The four-part series consisted of adaptations of novels written by Colin Watson, and in print they were part of his Flaxborough Chronicles, twelve novels in total. Inspector Purbright, played by Anton Rodgers, is an apparently placid small town policeman, but a man who sees more than he says, and someone who has a sharp eye for the corruption and scheming endemic among the councillors and prominent citizens of Flaxborough – a fictional town loosely based on Boston, Lincolnshire, where Watson worked as a journalist for many years. The TV Purbright was perhaps rather more Holmesian – with his pipe and tweeds – than Watson had intended, but the original novels Hopjoy Was Here, Lonelyheart 4122, The Flaxborough Crab and Coffin Scarcely Used, were lovingly treated. Unusually, for a TV production, the filming was done in a location not too far from the fictional Flaxborough – the Lincolnshire market town of Alford, just 25 miles from Watson’s Boston workplace. Click

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked.

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked. In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote