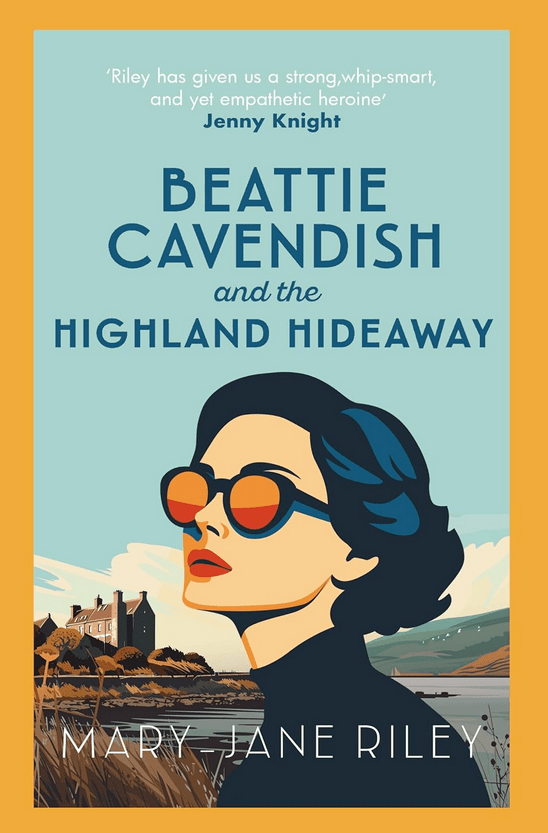

The book is set in the Britain of 1949. A strange place and no mistake. Strange? We had won the war, hadn’t we? To the victor the spoils? The reality is very different. The country is spent. Exhausted. Food and comfort are as scarce as they were six years earlier. Clement Attlee’s Labour government is trying to rebuild a country brought to its knees by five years of bombs, rationing, death and destruction. International politics and diplomacy are chaotic. America is, on the one hand, busy rounding up the less egregious former Nazi scientists and intelligence agents to work for them while, on the other, fiercely fighting the growing influence of the not-so-avuncular ‘Uncle Joe’ Stalin.

Caught up in this is British intelligence agent Beattie Cavendish. She works for the embryonic ‘listening agency’ GCHQ, and is sent up to Kilbray in the Scottish Highlands, posing as a secretarial instructor, to investigate a suspected leaking of information to the Russians. Readers new to the series will be unaware of Beattie’s recent history, of her time with the resistance in Occupied France, of her older brother, missing presumed dead, and her relationship with the battle-scarred Irish private investigator Corrigan. Rest assured, the author inserts these ‘catch-ups’ into the story smoothly and without disrupting the drive of the narrative.

When she arrives at Kilbray, Beattie expects to be reunited with her paternal uncle Howard, something of a family black sheep, but not unconnected with the intelligence community and international subterfuge. When she arrives at his loch-side cottage, he is not there. It is, however, something of a Marie Celeste situation. Whisky glasses are on the table, and food is in the cupboards. Also AWOL is Commander Henry Swaffer, the officer in charge of Kilbray. Local rumour has it that the thrice-married gentleman has gone on a fling with his latest girlfriend, a young German woman called Klara. That theory is severely tested when a dog-walker (where would crime fiction be without them?) finds Swaffer’s body washed up on the beach. It appears he has been strangled and his body cast into the waves.

Swaffer’s German friend Klara makes herself known to Beattie, but is then fatally stabbed in broad daylight in what appears to be a professional hit, and there is still no sign of uncle Howard. Beattie senses that the answers may lie in a mysterious establishment at Balgowrie, a place known as ‘the cooler’. During the war it was a sinister mix of refuge and prison, a place where agents who had lost their nerve, or escaped from failed missions, were confined. Beattie and Corrigan finally break into Balgowrie, and their invasion precipitates a violent and exciting dénouement.

Ann-Marie Riley also hints at the eternally fraught relationship between Britain and the Irish Republic. Thousands of men from southern Ireland gave their lives for Britain in The Great War, but by 1939, Ireland was resolutely neutral. Or was it? In the real world, men like Corrigan who had fought against the Nazis would be subsequently marginalised and denied pensions. Post 1945, committed Nazis like Célestin Lainé and Otto Skorzeny would be welcomed by the Irish state, and sheltered from the retribution facing fellow former Nazis. Riley isn’t trying to right ancient wrongs. She is merely setting out the sometimes unpleasant aspects of history and they actually happened.

You would be wrong to assume from the alliterative title and the cover graphics that this is a cosy crime story. Yes, Beattie is a perfect ladies’ book-reading-circle heroine. Certainly, there are occasional ‘Boys’ Own’ elements to the story, and perhaps the damaged PI Corrigan – who won his medals and his scares in the sheer hell of Monte Casino – can sometimes be too gung-ho for his own good, but Mary-Jane Riley takes a long hard look at a Britain struggling for identity, self-preservation, and searching for old certainties that have been blown away by the strong winds of a brutal post-war world. Beattie Cavendish and the Highland Hideaway will be published by Allison & Busby on 19th February.

Fancy a mint hardback copy of this book? Make a note of this code, and follow me on social media to enter the competition. UK addresses only, closes 10.00pm 22nd February.

Gunther is on nodding terms with such Nazi luminaries as Joseph Goebbels, Rheinhardt Heydrich and Arthur Nebe. In contrast, John Russell operates well below this elevated level of the Nazi heirarchy, although he references such monsters as Beria and Himmler, and does have face to face meetings with Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr (left).

Gunther is on nodding terms with such Nazi luminaries as Joseph Goebbels, Rheinhardt Heydrich and Arthur Nebe. In contrast, John Russell operates well below this elevated level of the Nazi heirarchy, although he references such monsters as Beria and Himmler, and does have face to face meetings with Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr (left). Gunther, in contrast, has known nothing but trauma in family terms. His wife dies in tragic circumstance and then his girlfriend – whi s regnant with his child – dies in one of the most infamous acts of WW2 – the sinking (by a Russian submarine) of the Wilhelm Gustloff in 1945. This account, detailed in The Other Side of Silence (2016) is, for me, the most compelling part of any of the Gunther novels:

Gunther, in contrast, has known nothing but trauma in family terms. His wife dies in tragic circumstance and then his girlfriend – whi s regnant with his child – dies in one of the most infamous acts of WW2 – the sinking (by a Russian submarine) of the Wilhelm Gustloff in 1945. This account, detailed in The Other Side of Silence (2016) is, for me, the most compelling part of any of the Gunther novels:

Some writers who have authored different series occasionally allow the main characters to meet each other, provided that they are contemporaries, of course. I’m pretty sure that Michael Connolly has allowed Micky Haller to bump into Harry Bosch, while Sunny Randall and Jesse Stone certainly knew each other in their respective series by Robert J Parker. Did Spenser ever join them in a (chaste) threesome? I don’t remember. John Lawton’s magnificent Fred Troy series ended with Friends and Traitors (2017), and since then he has been writing the Joe Wilderness books, of which this is the fourth. I can report, with some delight, that in the first few pages we not only meet Fred, but also Meret Voytek, the tragic heroine of A Lily of the Field, and her saviour – Fred’s sometime lover and former wife, Larissa Tosca. As an aside, for me A Lily of the Field is not only the best book John Lawton has ever written, but the most harrowing and heartbreaking account of Auschwitz ever penned. Click the link below to read more.

Some writers who have authored different series occasionally allow the main characters to meet each other, provided that they are contemporaries, of course. I’m pretty sure that Michael Connolly has allowed Micky Haller to bump into Harry Bosch, while Sunny Randall and Jesse Stone certainly knew each other in their respective series by Robert J Parker. Did Spenser ever join them in a (chaste) threesome? I don’t remember. John Lawton’s magnificent Fred Troy series ended with Friends and Traitors (2017), and since then he has been writing the Joe Wilderness books, of which this is the fourth. I can report, with some delight, that in the first few pages we not only meet Fred, but also Meret Voytek, the tragic heroine of A Lily of the Field, and her saviour – Fred’s sometime lover and former wife, Larissa Tosca. As an aside, for me A Lily of the Field is not only the best book John Lawton has ever written, but the most harrowing and heartbreaking account of Auschwitz ever penned. Click the link below to read more.

He is no James Bond figure, however. His dark arts are practised in corners, and with as little overt violence as possible. Hammer To Fall begins with a flashback scene,establishing Joe’s credentials as someone who would have felt at home in the company of Harry Lime, but we move then to the 1960s, and Joe is in a spot of bother. He is thought to have mishandled one of those classic prisoner exchanges which are the staple of spy thrillers, and he is sent by his bosses to weather the storm as a cultural attaché in Finland. His ‘mission’ is to promote British culture by traveling around the frozen north promoting visiting artists, or showing British films. His accommodation is spartan, to say the least. In his apartment:

He is no James Bond figure, however. His dark arts are practised in corners, and with as little overt violence as possible. Hammer To Fall begins with a flashback scene,establishing Joe’s credentials as someone who would have felt at home in the company of Harry Lime, but we move then to the 1960s, and Joe is in a spot of bother. He is thought to have mishandled one of those classic prisoner exchanges which are the staple of spy thrillers, and he is sent by his bosses to weather the storm as a cultural attaché in Finland. His ‘mission’ is to promote British culture by traveling around the frozen north promoting visiting artists, or showing British films. His accommodation is spartan, to say the least. In his apartment: So far, so funny – and Lawton (right) is in full-on Evelyn Waugh mode as he sends up pretty much everything and anyone. The final act of farce in Finland is when Joe earns his keep by sending back to London, via the diplomatic bag, several plane loads of …. well, state secrets, as one of Joe’s Russian contacts explains:

So far, so funny – and Lawton (right) is in full-on Evelyn Waugh mode as he sends up pretty much everything and anyone. The final act of farce in Finland is when Joe earns his keep by sending back to London, via the diplomatic bag, several plane loads of …. well, state secrets, as one of Joe’s Russian contacts explains: