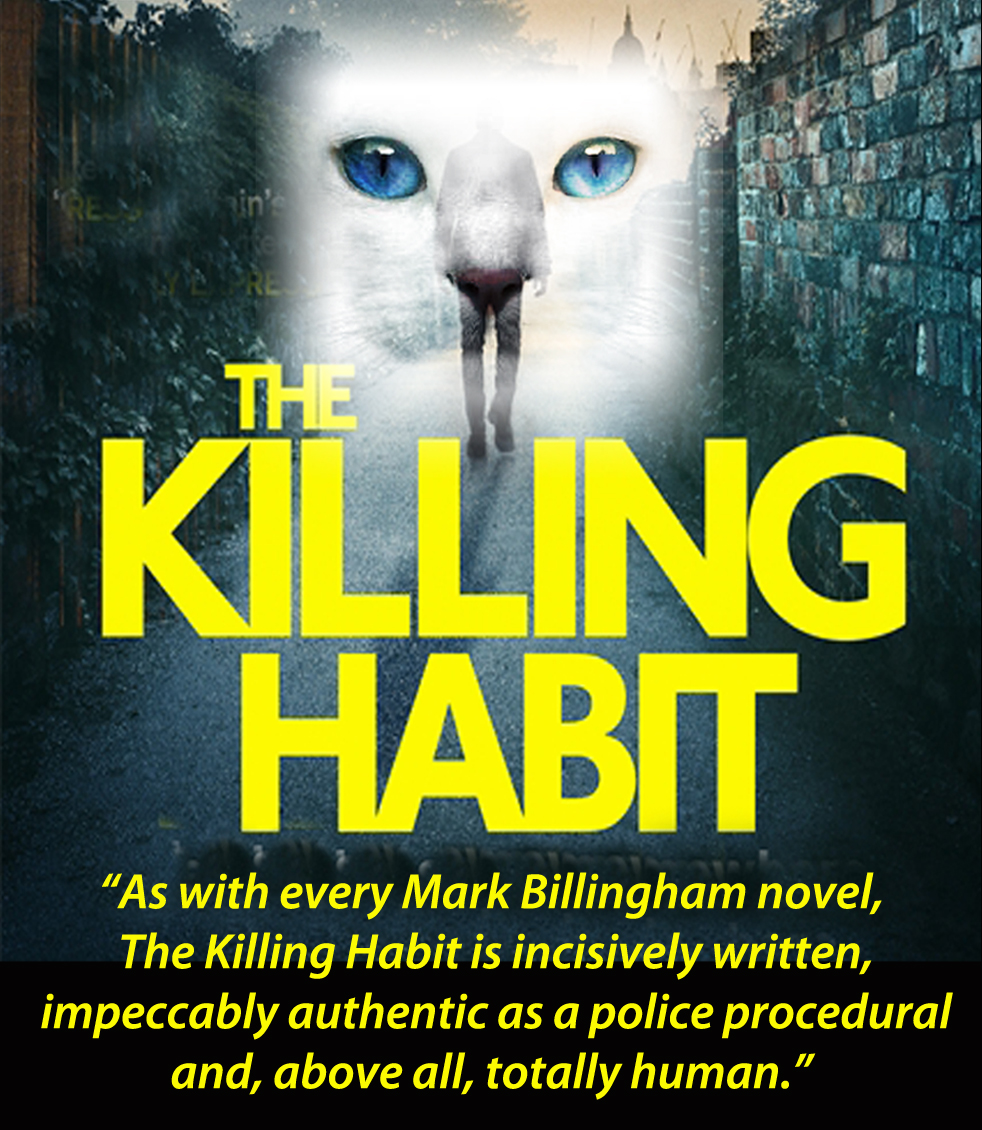

Mark Billingham’s perpetually disgruntled and discomforted London copper DI Tom Thorne returns in The Killing Habit for another three way battle. Three way? Yes, of course, because Thorne and his resolute allies sit on their stools in one corner of the triangular boxing ring, while in the blue corner are his politically correct bosses. In the red corner, of course, are the various chancers, petty and not-so-petty crooks who challenge the law on a daily basis.

The Thorne novels have a recurring cast list. As Salvatore Albert Lombino, aka Ed McBain said, quoting a 1917 popular song, “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here!” Indeed they are. Its members include Helen, Tom Thorne’s long suffering partner plus little boy Alfie, and the bizarrely tattooed and pierced Mancunian pathologist Phil Hendricks. We have Nicola Tanner the police officer scarred by the murder of her alcoholic partner, Susan, and the perpetually cautious DCI Russell Brigstocke. Between them, they pursue two killers; one who murders losers-in-the-Game-of-Life on the periphery of a drugs gang, and another who seems to be targeting lonely women via a match-making service.

The Thorne novels have a recurring cast list. As Salvatore Albert Lombino, aka Ed McBain said, quoting a 1917 popular song, “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here!” Indeed they are. Its members include Helen, Tom Thorne’s long suffering partner plus little boy Alfie, and the bizarrely tattooed and pierced Mancunian pathologist Phil Hendricks. We have Nicola Tanner the police officer scarred by the murder of her alcoholic partner, Susan, and the perpetually cautious DCI Russell Brigstocke. Between them, they pursue two killers; one who murders losers-in-the-Game-of-Life on the periphery of a drugs gang, and another who seems to be targeting lonely women via a match-making service.

It’s a staple of serial killer crime fiction that the bad guy starts out as a youngster by pulling wings off flies or torturing hamsters before graduating to ever darker deeds. Either that, or he is the victim of some terrible childhood trauma which poisons his view of humanity. I say ‘he’ and realise that I may be risking the wrath of the Equal Opportunities Police here, but I don’t recall reading a novel about female mass murderers. They may be out there. Numbered among their ranks may be homicidal Two Spirit Persons or Gender Fluid Otherkins. I do not know. If I have offended any potential killers by using the wrong pronoun, please accept my (almost) sincere apologies.

But I digress. Billingham puts Thorne on the trail of a serial killer – of cats. Why on earth? Two reasons. One is that nothing inflames the fury of Middle England like the killing of domestic animals. The debate that compares this crime with that of the murder of humans is for another day, but Billingham recognises that we are more likely to become incandescent over the death of a domestic pet than the death of a child. The second reason I have already suggested. If someone is waging a covert war on cats, is this just a prelude to something far, far worse? Indeed, it seems so. A succession of women meet their deaths at the hands of a killer who has hacked into the database of Made In Heaven, a low-rent match-making website.

Billingham gives us a parallel plot which eventually converges with the main story. A shadowy but powerful criminal organisation smuggles addictive synthetic drugs into British prisons. The recipients, grateful at the time, are eventually released into the wider world owing the gang an impossible amount of money, repayable only by becoming foot soldiers of the gang itself. An elderly woman, known only as “The Duchess” plays Postman Patricia in this deadly cycle of addiction and dependence and, when her role as amiable ‘auntie’ visiting prisoners is exposed, the connection between the drug scam and the dating killer is made.

As with every Mark Billingham novel, The Killing Habit is incisively written, impeccably authentic as a police procedural and, above all, totally human. No character walks onto the stage without their weaknesses and their frailties becoming exposed in the icy blue of the spotlight. We are not reading about cardboard cut-out people here: they are real, fallible and convincing. They may even be living a couple of doors down from you.

Just when you think that he has provided all the answers to the complex plot, and the characters are, to quote the only bit of Milton I can remember from ‘A’ Level, “calm of mind and all passion spent,” Billingham (right) provides a breathtaking epilogue which, in addition to turning my preconception on its head, (feel free to add your own metaphor) bites you on the bum, punches you in the gut, hits you over the head with a piece of four by two, takes the wind out of your sails and grabs you by the short-and-curlies. Hopefully recovering from this multiple assault, you will be hard pushed to disagree with me that this is a brilliant crime thriller written by a master storyteller at the very top of his game.

Just when you think that he has provided all the answers to the complex plot, and the characters are, to quote the only bit of Milton I can remember from ‘A’ Level, “calm of mind and all passion spent,” Billingham (right) provides a breathtaking epilogue which, in addition to turning my preconception on its head, (feel free to add your own metaphor) bites you on the bum, punches you in the gut, hits you over the head with a piece of four by two, takes the wind out of your sails and grabs you by the short-and-curlies. Hopefully recovering from this multiple assault, you will be hard pushed to disagree with me that this is a brilliant crime thriller written by a master storyteller at the very top of his game.

The Killing Habit is published by Litte, Brown and will be available on 14th June. For a review of the previous Tom Thorne novel, click the link to Love Like Blood.

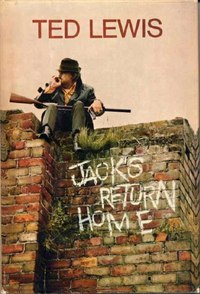

In 1965, All the Way Home and All the Night Through was published. It is a thinly disguised autobiographical novel, but Lewis’s breakthrough came in 1970 with the publication of Jack’s Return Home. The title was, bizarrely, taken from a spoof melodrama acted out by Tony Hancock, Hattie Jacques, Sid James and Bill Kerr as an episode of Hancock’s Half Hour. The novel, however, has few laughs. It describes the revenge mission of a London-based enforcer, Jack Carter, as he returns to his northern home town to investigate the death of his brother. The novel was adapted and filmed as Get Carter, and the rest, as they say, is history. Fame – and money – did not sit comfortably on Lewis’s shoulders, however. A mixture of drink and personal demons led to the break-up of his marriage, and a solitary return to Barton to live with his widowed mother. He died there, of heart failure connected to his ruinous drinking, in 1982.

In 1965, All the Way Home and All the Night Through was published. It is a thinly disguised autobiographical novel, but Lewis’s breakthrough came in 1970 with the publication of Jack’s Return Home. The title was, bizarrely, taken from a spoof melodrama acted out by Tony Hancock, Hattie Jacques, Sid James and Bill Kerr as an episode of Hancock’s Half Hour. The novel, however, has few laughs. It describes the revenge mission of a London-based enforcer, Jack Carter, as he returns to his northern home town to investigate the death of his brother. The novel was adapted and filmed as Get Carter, and the rest, as they say, is history. Fame – and money – did not sit comfortably on Lewis’s shoulders, however. A mixture of drink and personal demons led to the break-up of his marriage, and a solitary return to Barton to live with his widowed mother. He died there, of heart failure connected to his ruinous drinking, in 1982.

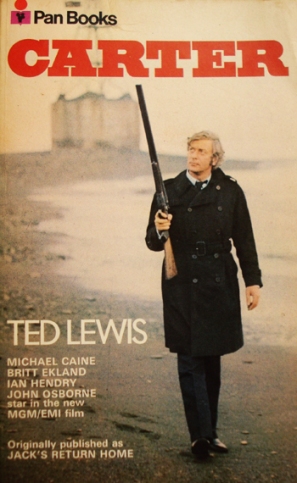

The centrepiece of Triplow’s book is, quite rightly, concerned with the novel itself, and its journey from a brutally honest and ground-breaking novel through to a partial re-imagining as one of the finest crime films ever made. Of Jack Carter, Triplow stresses that, despite the iconic image created by Michael Caine and director Mike Hodges

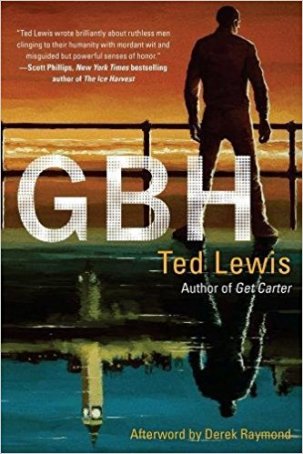

The centrepiece of Triplow’s book is, quite rightly, concerned with the novel itself, and its journey from a brutally honest and ground-breaking novel through to a partial re-imagining as one of the finest crime films ever made. Of Jack Carter, Triplow stresses that, despite the iconic image created by Michael Caine and director Mike Hodges Aside from describing what must have been harrowing conversations with Lewis’s widow and children, Triplow employs both the depth and breadth of his knowledge of British crime fiction to convince us just how good Ted Lewis was. It is intriguing that Triplow, supported by no less an authority than the magisterial Derek Raymond, makes a fascinating case for GBH being the apotheosis of Lewis’s talent, despite the groundbreaking style and success of Jack’s Return Home. Getting Carter is a sober and sombre account of the life of a man whose talent both defined and destroyed him, and Triplow makes no attempt to sanitise his subject. Lewis was clearly a man of huge personal charm when not in the grip of drink, but from the early days of illegally bought pints of beer in the 1950s through to the grim years of decline and death, alcohol had him firmly by the throat.

Aside from describing what must have been harrowing conversations with Lewis’s widow and children, Triplow employs both the depth and breadth of his knowledge of British crime fiction to convince us just how good Ted Lewis was. It is intriguing that Triplow, supported by no less an authority than the magisterial Derek Raymond, makes a fascinating case for GBH being the apotheosis of Lewis’s talent, despite the groundbreaking style and success of Jack’s Return Home. Getting Carter is a sober and sombre account of the life of a man whose talent both defined and destroyed him, and Triplow makes no attempt to sanitise his subject. Lewis was clearly a man of huge personal charm when not in the grip of drink, but from the early days of illegally bought pints of beer in the 1950s through to the grim years of decline and death, alcohol had him firmly by the throat.

The van skids to a halt on the lonely hill top lane. Occasional distant lights from isolated farms and cottages are all that pierce the darkness. The young men inside the van giggle as they open the rear doors and throw the girl from the dirty mattress on which she has been sprawled. She hits the roadside with a body-jarring crunch.

The van skids to a halt on the lonely hill top lane. Occasional distant lights from isolated farms and cottages are all that pierce the darkness. The young men inside the van giggle as they open the rear doors and throw the girl from the dirty mattress on which she has been sprawled. She hits the roadside with a body-jarring crunch.