Bernie Gunther is the anti-hero of fourteen novels by the late Philip Kerr. Berlin cop, turned private investigator, sometime employee of Goebbels and Heydrich, and finally an international pariah, Gunther’s exploits span post Great War Germany to international intrigue in the 1950s. John Russell is an Anglo American journalist who begins the series of seven books by David Downing based in Germany. The books are all named after railway stations and span the years 1938 – 1948.

BERNIE GUNTHER

Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir series was published between 1989 and 1991, and introduced the world to Bernie Gunther. Strangely, it wasn’t until 2006 that the books March Violets, The Pale Criminal and A German Requiem were followed up with The One from the Other, and until his death the Edinburgh-born author brought us regular episodes from the life of his tough, resourceful and compassionate hero. The final novel in the series, Metropolis, was published in 2019 after Kerr’s death and, ironically, is set in the earliest part of Gunther’s career.

Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir series was published between 1989 and 1991, and introduced the world to Bernie Gunther. Strangely, it wasn’t until 2006 that the books March Violets, The Pale Criminal and A German Requiem were followed up with The One from the Other, and until his death the Edinburgh-born author brought us regular episodes from the life of his tough, resourceful and compassionate hero. The final novel in the series, Metropolis, was published in 2019 after Kerr’s death and, ironically, is set in the earliest part of Gunther’s career.

To begin with, Gunther has survived two world wars and seen death in all its forms. However, what makes the series fascinating is the challenge he faces, which is to keep his moral compass steady. Uniquely amongst fictional detectives, Bernie has to operate during the dark and savage days of the Third Reich.

Having returned from the trenches of The Great War, Gunther becomes a member of Kripo (Kriminalpolizei), the investigative branch of the Berlin police. During the turbulent years of the 1930s, he tries to steer an even and honest course between the rival political thuggery of the Nazis and the Communists, and when Hitler seizes power he eventually finds himself forced to join the SD (Sicherheistdienst), the intelligence division of the SS. Sent to Ukraine as part of an extermination group but having no stomach for this, he is shunted into the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front, and is captured by the Russians. After the War, his ambiguous record makes him a person of interest to the Americans, the Russians and the leadership of the GDR, and he leads a dangerous existence among Nazi refugees in Cuba and South America.

Like John Lawton and George Macdonald Frazer, with their respective Freddie Troy and Flashman series, Kerr places fictional characters within real events and alongside celebrated or notorious historical figures. And, he manages to do so in a fascinating and totally plausible way. Assuming that Gunther was born in the mid-to-late 1890s, he can still be at work in the mid 1950s, albeit a heavier, slower and more breathless version of his former self – a latter day Ulysses.

“Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will to strive, to seek, to find and not to yield,” writes Kerr of his hero.

The author’s style, particularly his use of dialogue, set him apart from most contemporary writers. His books were genuine literature, although I suspect written without literary pretension. In Prague Fatale, he described Gunther meeting an American war correspondent in a Berlin blackout:

The author’s style, particularly his use of dialogue, set him apart from most contemporary writers. His books were genuine literature, although I suspect written without literary pretension. In Prague Fatale, he described Gunther meeting an American war correspondent in a Berlin blackout:

“His Old Spice and Virginia tobacco came ahead of him like a motorcycle outrider with a pennant on his mudguard. Solid footsteps bespoke sturdy wing-tip shoes that could have ferried him across the Delaware….his sweet and minty breath smelled of real toothpaste and testified to his having access to a dentist with teeth in his head who was still a decade off retirement.”

In his toughness, moral strength and cynical view of the world, Gunther is very much the heir of Philip Marlowe. His descriptions, sarcasm and one-line put-downs can be very funny. This is a line from A Quiet Flame, which came out in 2008:

“The isosceles of muscles between her chin and her collar-bone had stiffened, like something metallic. If I’d had a little wand I could have used it to tap out the part for triangle in the Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin.”

For more on Bernie Gunther, click the link below

https://fullybooked2017.com/tag/bernie-gunther/

JOHN RUSSELL

Russell is an English journalist with an American mother. Until 1927 he was a member of the Communist Party but, like many others, he fell out of love with the kind of socialism being espoused by Stalin and his acolytes. After serving with the British army in The Great War, he moved to Berlin, married Ilse, and they had a son – Paul. The marriage didn’t last.

In terms of the actual time setting, Wedding Station (2021) gives us the earliest glimpse of John Russell.It is just months after Hitler’s rise to power, and Russell watches the Reichstag burn. Four weeks after Hitler’s accession, brownshirt mobs stalk the streets and the press prints what the Party tells it to.

In terms of the actual time setting, Wedding Station (2021) gives us the earliest glimpse of John Russell.It is just months after Hitler’s rise to power, and Russell watches the Reichstag burn. Four weeks after Hitler’s accession, brownshirt mobs stalk the streets and the press prints what the Party tells it to.

In the first book (in publication terms) in the series, Zoo Station (2007) we are are introduced to Russell. It is 1939, Berlin, and Russell is an accredited American journalist, safe (for now) from the excesses of Hitler’s government. He has a glamorous girlfriend in Effie Koenen, who is a rising star in German cinema, but he still has a relatively civilised relationship with Ilse – and her new husband – and has regular access to Paul.

His communist background, American passport and fluency in both Russian and German make John Russell a unique target for the intelligence services of all the major powers and, almost like a serial bigamist he becomes wedded to the Sicherheitsdienst, the NKVD, the Abwehr, and the OSS. He plays each one off against the other, more or less successfully and, along with Effie and son Paul, survives the war, but finds ‘the peace’ post 1945 just as traumatic. In Masaryk Station (2013) set in 1948, Russell is told by a Soviet stooge that there is still a war, but that it is different:

“That war is over. It’s time you realised that another struggle – one every bit as crucial – is now underway.”

One of the main anxieties in Russell’s complex life is his son Paul. As the boy reaches his teens he becomes – like millions of other German lads – a member of the Hitlerjugend, and this threatens to drive a wedge between father and so. In Stettin Station (2009) we are in November/December 1941, and a famed German air ace of WW1, Ernst Udet is dead. In fact, he shot himself, disillusioned with Luftwaffe chief Goering, and the general conduct of the war, but for the purposes of national solidarity the official story is that he died in a plane crash. As his elaborate funeral cortege passes their viewing point, Paul chides his father for not making the Seig Heil salute with enough reverence. Russell dreads the day when Paul is conscripted to the army and sent to fight on the Eastern Front.

One of the main anxieties in Russell’s complex life is his son Paul. As the boy reaches his teens he becomes – like millions of other German lads – a member of the Hitlerjugend, and this threatens to drive a wedge between father and so. In Stettin Station (2009) we are in November/December 1941, and a famed German air ace of WW1, Ernst Udet is dead. In fact, he shot himself, disillusioned with Luftwaffe chief Goering, and the general conduct of the war, but for the purposes of national solidarity the official story is that he died in a plane crash. As his elaborate funeral cortege passes their viewing point, Paul chides his father for not making the Seig Heil salute with enough reverence. Russell dreads the day when Paul is conscripted to the army and sent to fight on the Eastern Front.

John Russell’s contact with senior Nazi officials is limited, but he does occasionally come face to face with Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the Abwehr, the intelligence service of the German army. One of Russell’s many uneasy allegiances is to the Abwehr which, in fiction if not in fact, has been seen as the acceptable face of the Third Reich. This is perhaps born out by the fact that Canaris was executed for treason on 9th April 1945, in the dying days of Hitler’s regime.

Russell’s connection with Joseph Goebbels is more distant, and it is through Effi Koenen. She is probably the most ‘box office’ star of German cinema, and Goebbels – as propaganda minister – has absolute control over what films can be made, and what message they send out. As such, Effi is much sought after. Again in Stettin Station David Downing presents us with the bitter irony that Effi – pale, dark haired and sexually vibrant – is required to play a Jewish woman in a film with a vehemently anti-Jewish screenplay. For full reviews of Silesian Station and Wedding Station click the link below.

https://fullybooked2017.com/tag/david-downing/

IN PART TWO OF THIS FEATURE

I will examine the differences – and similarities between Bernie Gunther and John Russell.

Gunther is on nodding terms with such Nazi luminaries as Joseph Goebbels, Rheinhardt Heydrich and Arthur Nebe. In contrast, John Russell operates well below this elevated level of the Nazi heirarchy, although he references such monsters as Beria and Himmler, and does have face to face meetings with Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr (left).

Gunther is on nodding terms with such Nazi luminaries as Joseph Goebbels, Rheinhardt Heydrich and Arthur Nebe. In contrast, John Russell operates well below this elevated level of the Nazi heirarchy, although he references such monsters as Beria and Himmler, and does have face to face meetings with Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr (left). Gunther, in contrast, has known nothing but trauma in family terms. His wife dies in tragic circumstance and then his girlfriend – whi s regnant with his child – dies in one of the most infamous acts of WW2 – the sinking (by a Russian submarine) of the Wilhelm Gustloff in 1945. This account, detailed in The Other Side of Silence (2016) is, for me, the most compelling part of any of the Gunther novels:

Gunther, in contrast, has known nothing but trauma in family terms. His wife dies in tragic circumstance and then his girlfriend – whi s regnant with his child – dies in one of the most infamous acts of WW2 – the sinking (by a Russian submarine) of the Wilhelm Gustloff in 1945. This account, detailed in The Other Side of Silence (2016) is, for me, the most compelling part of any of the Gunther novels: Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir series was published between 1989 and 1991, and introduced the world to Bernie Gunther. Strangely, it wasn’t until 2006 that the books March Violets, The Pale Criminal and A German Requiem were followed up with The One from the Other, and until his death the Edinburgh-born author brought us regular episodes from the life of his tough, resourceful and compassionate hero. The final novel in the series, Metropolis, was published in 2019 after Kerr’s death and, ironically, is set in the earliest part of Gunther’s career.

Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir series was published between 1989 and 1991, and introduced the world to Bernie Gunther. Strangely, it wasn’t until 2006 that the books March Violets, The Pale Criminal and A German Requiem were followed up with The One from the Other, and until his death the Edinburgh-born author brought us regular episodes from the life of his tough, resourceful and compassionate hero. The final novel in the series, Metropolis, was published in 2019 after Kerr’s death and, ironically, is set in the earliest part of Gunther’s career. The author’s style

The author’s style In terms of the actual time setting, Wedding Station (2021) gives us the earliest glimpse of John Russell.It is just months after Hitler’s rise to power, and Russell watches the Reichstag burn. Four weeks after Hitler’s accession, brownshirt mobs stalk the streets and the press prints what the Party tells it to.

In terms of the actual time setting, Wedding Station (2021) gives us the earliest glimpse of John Russell.It is just months after Hitler’s rise to power, and Russell watches the Reichstag burn. Four weeks after Hitler’s accession, brownshirt mobs stalk the streets and the press prints what the Party tells it to. One of the main anxieties

One of the main anxieties

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth?

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth? Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

“One of the greatest anti-heroes ever written,” says Lee Child of Bernie Gunther, the world weary, wise-cracking former German cop, and sometime acquaintance of such diverse historical characters as Reinhard Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Eva Peron and William Somerset Maugham. I was several chapters into this, the latest episode in Gunther’s career, when I heard the dreadful news of the death of his creator, Philip Kerr (left) at the age of 62. “No age at all,” as the saying goes.

“One of the greatest anti-heroes ever written,” says Lee Child of Bernie Gunther, the world weary, wise-cracking former German cop, and sometime acquaintance of such diverse historical characters as Reinhard Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Eva Peron and William Somerset Maugham. I was several chapters into this, the latest episode in Gunther’s career, when I heard the dreadful news of the death of his creator, Philip Kerr (left) at the age of 62. “No age at all,” as the saying goes.

Hitler could certainly have taken a lesson from the Old Man (Adenauer, left) It was not the men with guns who were going to rule the world but businessmen …. with their slide rules and actuarial tables, and thick books of obscure new laws in three different languages.”

Hitler could certainly have taken a lesson from the Old Man (Adenauer, left) It was not the men with guns who were going to rule the world but businessmen …. with their slide rules and actuarial tables, and thick books of obscure new laws in three different languages.”

I met Joseph Knox (left) at a publisher’s showcase event in London, where he presented his debut novel,

I met Joseph Knox (left) at a publisher’s showcase event in London, where he presented his debut novel,  Just as George MacDonald Fraser had his magnificent bounder Harry Flashman working his way through all the major political and military events of the the second half of the 19th century, so Philip Kerr (right) has positioned his wearily honest – but cynical – German cop Bernie Gunther in the 20th. We know Gunther fought in The Great War, but his service there is only, thus far, alluded to. We have seen him interact with most of the significant players in the decades spanning the rise of the Nazis through to their defeat and escape into post-war boltholes such as Argentina and Cuba. In the 13th book of this brilliant series, Gunther, joints creaking with advancing old age, is now working for an insurance company who want him to investigate a possible scam involving a sunken ship. His work takes him to Athens, where he discovers an unpleasantly familiar link to evil deeds committed under the baleful gaze of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen. Some of Bernie Gunther’s earlier exploits are covered

Just as George MacDonald Fraser had his magnificent bounder Harry Flashman working his way through all the major political and military events of the the second half of the 19th century, so Philip Kerr (right) has positioned his wearily honest – but cynical – German cop Bernie Gunther in the 20th. We know Gunther fought in The Great War, but his service there is only, thus far, alluded to. We have seen him interact with most of the significant players in the decades spanning the rise of the Nazis through to their defeat and escape into post-war boltholes such as Argentina and Cuba. In the 13th book of this brilliant series, Gunther, joints creaking with advancing old age, is now working for an insurance company who want him to investigate a possible scam involving a sunken ship. His work takes him to Athens, where he discovers an unpleasantly familiar link to evil deeds committed under the baleful gaze of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen. Some of Bernie Gunther’s earlier exploits are covered

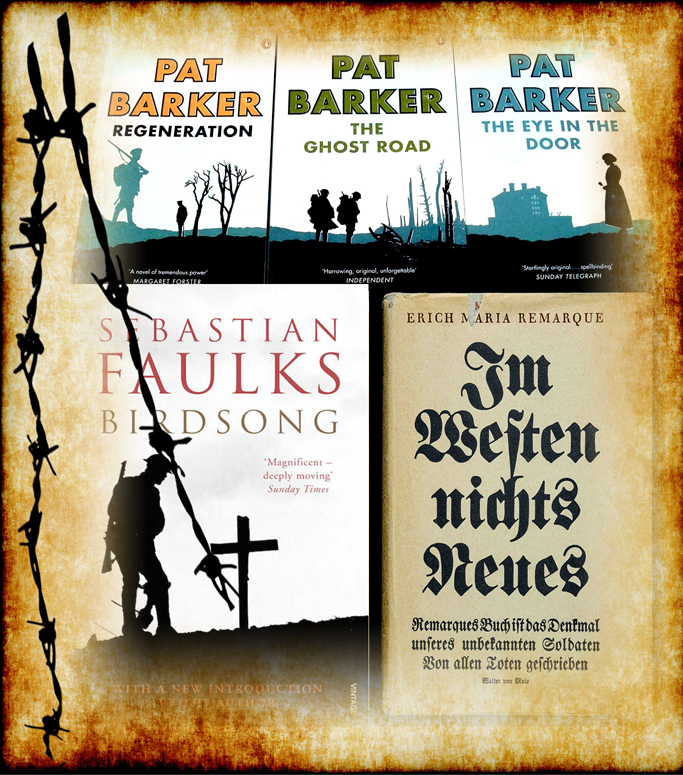

What needs to be held up like a bright lantern in our search for good WWI crime fiction, is the fact that those six years are like no other in British history. They have produced a mythology which is unique in modern memory, and with it a collection of tropes, images, phrases and conventions, all of which find their way into the consciousness of writers and readers. Military historians tell only part of the story: the Alan Clark theory of The Donkeys and the anti-war polemic of the the 1960s and 70s has one version of events; more recent accounts of the war by revisionist historians such as John Terrain and Gary Sheffield tell another tale altogether. In considering books and writers for this feature I have used two criteria. Firstly, there must be crime involved that is distinct from the licensed slaughter of wartime and, secondly, the events of the war must cast their shadows over the narrative either in a contemporary sense or in the form of a social or political legacy.

What needs to be held up like a bright lantern in our search for good WWI crime fiction, is the fact that those six years are like no other in British history. They have produced a mythology which is unique in modern memory, and with it a collection of tropes, images, phrases and conventions, all of which find their way into the consciousness of writers and readers. Military historians tell only part of the story: the Alan Clark theory of The Donkeys and the anti-war polemic of the the 1960s and 70s has one version of events; more recent accounts of the war by revisionist historians such as John Terrain and Gary Sheffield tell another tale altogether. In considering books and writers for this feature I have used two criteria. Firstly, there must be crime involved that is distinct from the licensed slaughter of wartime and, secondly, the events of the war must cast their shadows over the narrative either in a contemporary sense or in the form of a social or political legacy.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann. A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS.

A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS. the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.

the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.