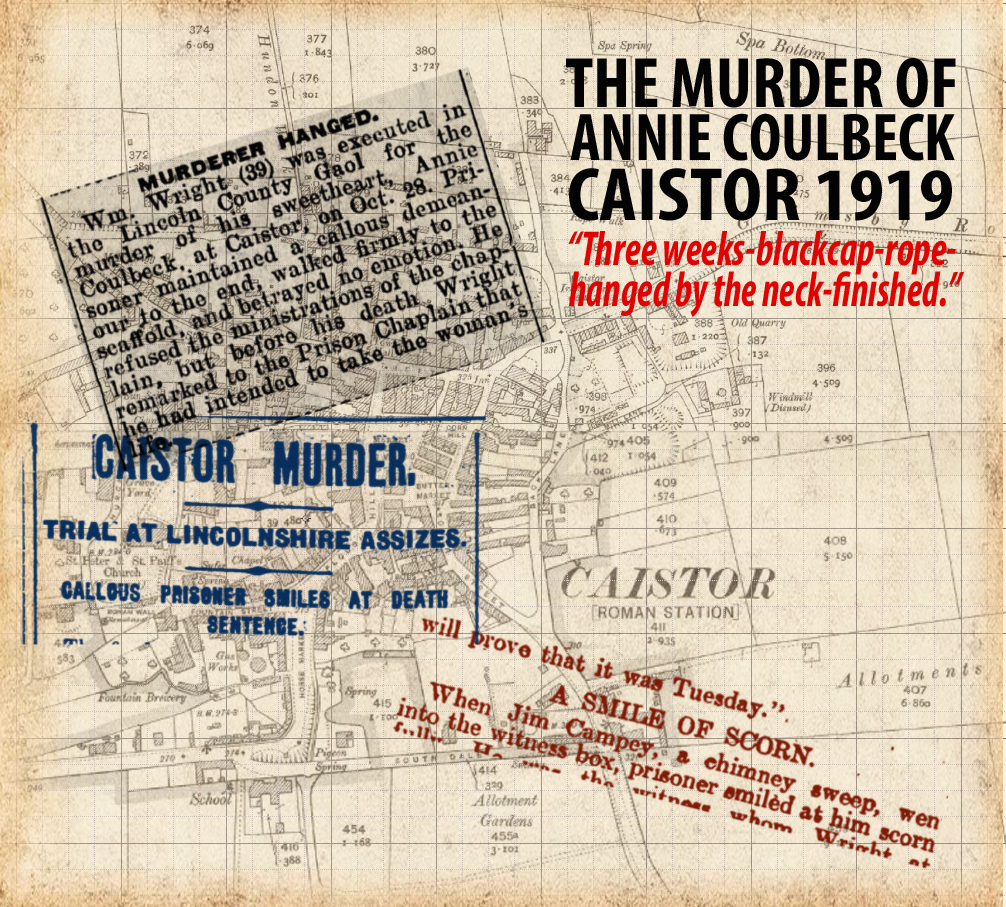

SO FAR: Caistor, North Lincolnshire, October 1919. William Wright (39), a former soldier, is now working in a sawmill in nearby Moortown. He has a reputation as a ne’er-do-well and sometime vagrant, with a long criminal record. He has been in a relationship with Annie Coulbeck, (34). She is carrying his child.

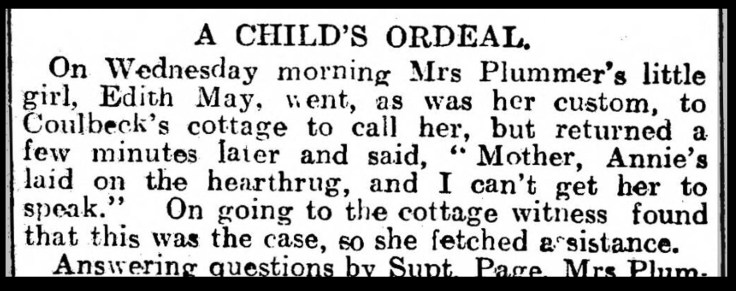

Annie, who lives in a cottage at Pigeon Spring on Horsemarket. has been working as a nanny, looking after the children of Mrs Plummer. On the morning of Wednesday 29th October, Annie has not turned up for work, so Mrs Plummer sends one of her children to Annie’s cottage to see if she was unwell.

Annie Coulbeck had been strangled, and had been dead for some hours, and it goes without saying that her unborn child – some seven months in her womb – had shared its mother’s fate. At the coroner’s inquest, the doctor gave his report:

It was no secret that Annie Coulbeck and William Wright were lovers, and when police visited him at his home in South Dale, Caistor, his admission was astonishingly matter-of-fact:

“Last night, a little after 10 o’clock, I left the Talbot public house. I had a lot of drink and went down to Annie Coulbecks house. I asked her where she had got the brooch from which she was wearing. She said it was her mothers. I told her I did not think it was. I told her I thought it was one of her fancy men’s. She said, “I’m sure it is not, Bill.” I told her I would finish her if she did not tell me whose it was. I strangled her with my hands and left her dead. I put the lamp out and went home.”

The Talbot in Caistor (above) is no longer a pub, but if its walls could talk, they might bear witness to a chilling conversation William Wright had with a fellow drinker, a local chimney sweep.

The umbilical cord is often used as a metaphor for two things being inextricably joined, but it also has a presence in the British legal system, particularly in the case of murdered babies. Criminal history, particularly back in the day, is full of young women being tried for murder after they have killed an unwanted new-born baby. For it to be murder, it has to be established that the infant had an independent existence, and it is clear that the child Annie Coulbeck was carrying had no such thing. However, in my book, William Wright was as guilty of murdering that child – his child – as he was of killing its mother.

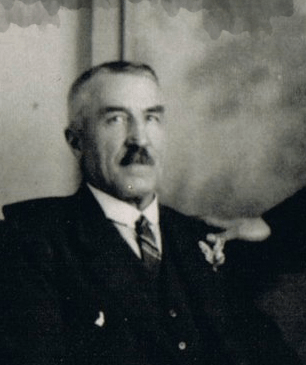

Wright, in his drunken estimation that it would take just three weeks from the death of Annie Coulbeck to his appointment on the gallows, was as ignorant of the legal system as he was of the way decent human beings should behave. The law took its rather ponderous course, and after the Coroner’s Inquest and then Magistrate Court, William Wright finally appeared at Lincoln Assizes, before Mr Justice Horridge (left) on Monday 2nd February 1920. It was a perfunctory affair. Wright’s defence lawyers, as they were bound to do, came up with the only possible plea – that Wright was insane. They cited his war experience, and the fact that members of his family had been committed to institutions. Neither judge nor jury were impressed and, as Wright had predicted, hunched over his beer in The Talbot, the judge donned the Black Cap. An appeal was lodged, but failed.

Throughout the legal process, Wright had shown not one iota of remorse, nor did he betray any concern about what awaited him.

Wright was executed at Lincoln Castle on 10th March 1920. He had refused the ministrations of the prison chaplain, and the last face he would have focused on before the hood was placed over his head and he dropped to his death was the grim visage of executioner Thomas Pierrepoint (right), uncle of the more celebrated hangman Albert Pierrepoint, subject of the excellent film (2005) featuring Timothy Spall as the man who hanged, among others, Ruth Ellis and dozens of Nazi war criminals. The corpses of executed criminals at Lincoln Castle were interred in a little graveyard situated on the Lucy Tower. If ever a soul deserved to rot in hell, it is that of William Wright.

FOR MORE HISTORIC MURDERS IN LINCOLNSHIRE

CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW