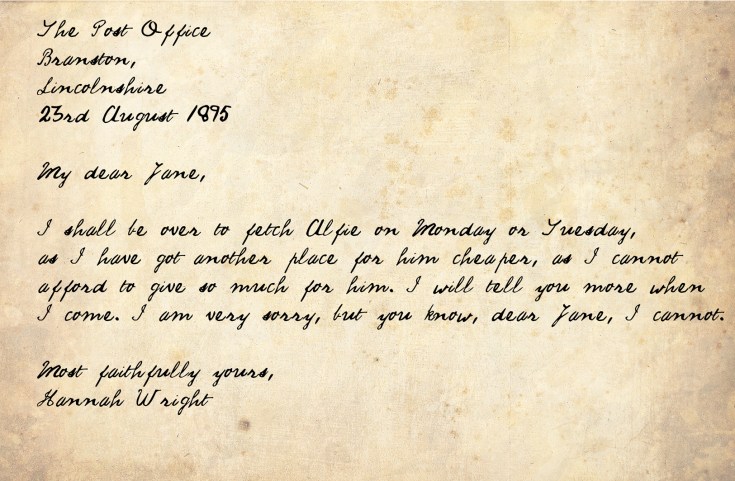

SO FAR: August 1895. Hannah Elizabeth Wright, 23, gave birth to a little boy, Alfred Edward, in November 1893. The boy’s father has disappeared, leaving Hannah to deal with the situation. Alfie has been in the care of a Miss Flear, who lives near Newark, but Hannah can no longer afford to give Miss Flear the money she requires, and has collected the little boy, and returned to Lincoln on the evening of 26th August. The following day, having not returned to their home in Alexandra Terrace the previous evening, she tells her brother and his wife that the boy is still in Newark, and is being put up for adoption.

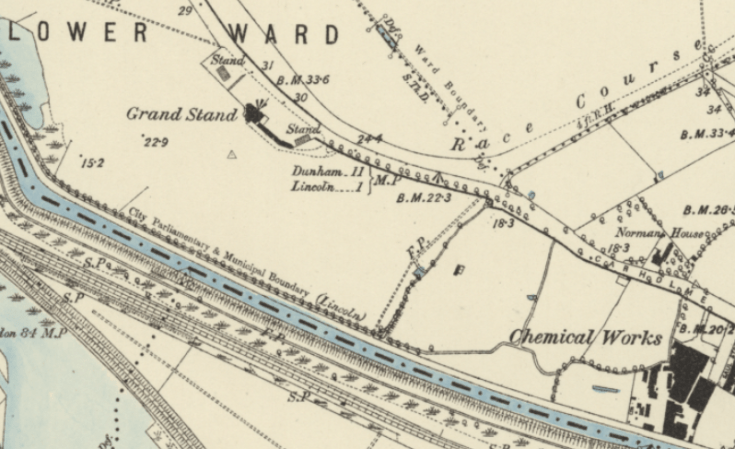

Foss Dyke is a canal that links Lincoln with the River Trent at Torksey. Some historians insist that it was built by the Romans, while others believe that it dates back to the 12th century. It was along the bank of this ancient waterway, between Jekyll’s Chemical chemical works and the back of the racecourse grandstand, that on the evening of Monday 26th August our story continues. A young man called James Fenton was sitting on a bench with a lady friend, when a woman passed them, walking in the direction of Pyewipe. She was carrying a bundle, but they heard a whimpering sound, and they realised that she was holding a child. It was, by this time almost dark, but when the woman passed them again, this time heading back towards the city, she was empty handed. Thinking this strange, Fenton followed the woman at a distance, but lost her somewhere in the vicinity of Alexandra Terrace. The following morning, Tuesday, a man on his way to work had an unpleasant surprise. He was later to tell the court:

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

Whatever the state of Hannah Wright’s mind when she drowned her son, and during her long months before she came to trial, when she finally appeared before Mr Justice Day at the end of November she must have had a cold awakening as to what possibly lay ahead of her. Since September, there had been various intimations in the press that Hannah was, to use the vernacular, “not quite all there” but there was no medical evidence that she was weak minded or mentally deficient. Her defence barrister made a rather odd case, as was reported in The Lincolnshire Echo on Tuesday 26th November 1895:

“The Judge pointed out that the defence was rather an unusual one, namely of a two-fold character, one contention being that the prisoner never committed the crime all, and it she did do so that her mind was unhinged at the time. As to the plea of insanity he did not see that there was the slightest evidence to show that her mind was diseased. The jury retired to consider their verdict at 5.20, and returned into Court after an absence of twenty-seven minutes. They found the prisoner guilty, with a strong recommendation mercy. Prisoner made no reply to the question put to her by the Clerk whether she wished to say anything before sentence was passed. The Judge, who appeared be deeply affected, said the jury had simply discharged their duty, painful though undoubtedly was. With regard to the recommendation to mercy his Lordship said he would wish and beg her not to place undue reliance upon that recommendation. His Lordship then passed sentence of death in the usual manner. Prisoner fainted as she was being led down the dock steps.”

The general public in Lincoln and round about had become very involved in this tragic case, and even before Hannah collapsed on the steps of the dock, a petition was created and with thousands of names on it, presented to the Home Secretary, Sir Matthew White Ridley KCB. Within days, the threat of the hangman’s noose was lifted.

Peter Spence, a distant relative of Hannah, and to whom I am indebted for sharing his research, suggests that this story has something of Thomas Hardy about it, but we would do well to remember that poor Tess (of the D’Urbervilles) is hanged for her crime. Not only did Hannah survive, but she was released from prison in Aylsbury, apparently going straight to London to work as a servant.

Strangely, that is where the story ends. Peter Spence, and that eminent compiler of Lincolnshire crime stories Mick Lake, like me, have found no trace of what became of Hannah. This is unusual, given the amount of information available on modern genealogy websites, but it it is what it is. There are a couple of inconclusive mentions in the 1939 register, but no evidence that these people are ‘our’ Hannah. There is this, but is it feasible that a servant girl could have eventually returned to Lincolnshire and died at the age of 89, leaving the sum of £2552 10s – nearly £47,000 in today’s money? Perhaps that is a mystery for another day.

I have been researching and writing about historic Lincolnshire murders for some years,and those wishing to find out more about our county’s macabre past should click this link

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.