Was there ever such a yawning gulf between a man and his words as with AE Housman? By all accounts he was prissy, pedantic and and vindictive towards Cambridge undergraduate pupils who failed to meet his expectations in their studies of the classics. He was memorably described as “descended for a long line of maiden aunts”. He never knew reciprocated love. His homosexual yearning for one or two men of his acquaintance was never returned, given the grim frown society bestowed on such things at the time. And yet he wrote some of the most passionate, evocative and memorable poems in the English language, poems which spoke of love, death and grief – all set against a haunted – and haunting – English landscape.

Was there ever such a yawning gulf between a man and his words as with AE Housman? By all accounts he was prissy, pedantic and and vindictive towards Cambridge undergraduate pupils who failed to meet his expectations in their studies of the classics. He was memorably described as “descended for a long line of maiden aunts”. He never knew reciprocated love. His homosexual yearning for one or two men of his acquaintance was never returned, given the grim frown society bestowed on such things at the time. And yet he wrote some of the most passionate, evocative and memorable poems in the English language, poems which spoke of love, death and grief – all set against a haunted – and haunting – English landscape.

I speak, of course, about A Shropshire Lad, a collection of sixty three poems published, initially at his own expense, in 1896. If we are looking for irony and contradictions here, perhaps the most startling is that the poems were written in his house in Highgate, London – some 150 miles from the hills and valleys where the poems were set. There is little evidence that Housman even knew – first hand – Shropshire well at all. He was born in a village near Bromsgrove, and although Worcestershire shares a border with Shropshire, there is no line of sight between the two locations. Bredon Hill, however – which he immortalised in one of his most celebrated poems – is in Worcestershire, and is perhaps one of his “blue remembered hills.”

Housman was a classical scholar, and his day job was that of a university lecturer, first in London and then in Cambridge. Although his ashes (he died in 1936) are buried in Ludlow churchyard, there is little to connect – physically – Housman with Shropshire. So what prompted him to immortalise such places as Bredon, Clun, Ludlow and Wenlock Edge? Better scholars than I have discussed this without providing a definitive answer, but for what it’s worth, I think the answer may be that the poems are an extended metaphor involving Housman’s homosexuality.

It is a matter of record that the love of Housman’s life was a fellow Oxford student, Moses John Jackson (right). The passion was in one direction only, and Jackson later placed some geographical distance between himself and Housman. So what has this to do with the poetry? The pervading theme in A Shropshire Lad is a longing, a yearning for something that can never come again, places and people irretrievably lost, a memory of earlier years. Housman never courted a lass In Summertime On Bredon, and although Jackson died at a respectable old age, just months before Housman, there is a palpable sense of longing in the words “by brooks too broad for leaping, the light-foot lads are laid”. It is hard to ignore that the central characters in many of the poems are young men who died early. Take the two young men who speak in “Is My Team Ploughing?” One is dead and buried, but longs for information about his old life. The other speaks to him kindly, but is sleeping with the dead man’s former girlfriend.

It is a matter of record that the love of Housman’s life was a fellow Oxford student, Moses John Jackson (right). The passion was in one direction only, and Jackson later placed some geographical distance between himself and Housman. So what has this to do with the poetry? The pervading theme in A Shropshire Lad is a longing, a yearning for something that can never come again, places and people irretrievably lost, a memory of earlier years. Housman never courted a lass In Summertime On Bredon, and although Jackson died at a respectable old age, just months before Housman, there is a palpable sense of longing in the words “by brooks too broad for leaping, the light-foot lads are laid”. It is hard to ignore that the central characters in many of the poems are young men who died early. Take the two young men who speak in “Is My Team Ploughing?” One is dead and buried, but longs for information about his old life. The other speaks to him kindly, but is sleeping with the dead man’s former girlfriend.

“Is my friend hearty,

Now I am thin and pine?

And has he found to sleep in

A better bed than mine?”

“Yes lad I lie easy,

I lie as lads would choose.

I cheer a dead man’s sweetheart,

Never ask me whose.”

Moses John Jackson didn’t die early, but he may as well have done in terms of his relationship with Housman. The love that Housman felt was inexpressible in those days, at least in public. Instead, he constructed a beautiful metaphor (best summed up in his words below) which has entranced readers – while they may not fully comprehend it – ever since.

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

One of the most striking things about the poems in A Shropshire Lad is how natural they are as musical lyrics. Rather in the same way the words of Goethe and Schiller captivated Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann, Housman’s poems proved irresistible to a generation of English composers. in the early twentieth century. Most of these were hardly names to rival the great Germans, but one was a giant. Perhaps the most English of composers, Ralph Vaughan Williams, set six of the poems in a song cycle called On Wenlock Edge. I will put a case for onother composer, George Butterworth. Had he survived The Great War, he would now stand alongside Purcell, Elgar and RVW as giants of English music. His setting of Is My Team Ploughing? is as poignant and heartbreaking as anything penned by Schubert. You can listen to the song by clicking the video below.

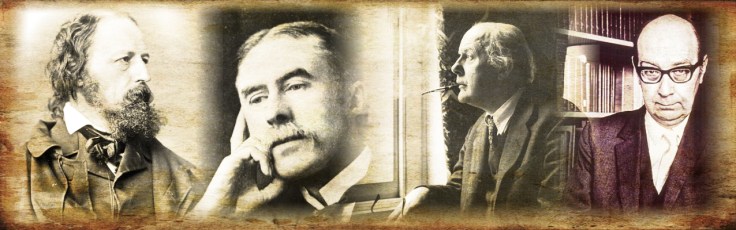

IN PART THREE

A MEDIOCRE POET WITH A GIFT FOR TV,

OR SOMEONE MORE PROFOUND?

I’ll start with Tennyson, but offer a word of caution. Look hard at his poetry and you may not see obvious indicators of his Lincolnshire roots. But let me turn it on its head. Visit the village of Somersby, an isolated and lonely hamlet deep in the Wolds of Lincolnshire, the place where he spent his boyhood. His father was rector of the church (above), and he would have wandered the isolated lanes thereabouts as a boy. The streams, the rustic bridges, the grand old houses still exist, and are little different from when he knew them. The walled garden in

I’ll start with Tennyson, but offer a word of caution. Look hard at his poetry and you may not see obvious indicators of his Lincolnshire roots. But let me turn it on its head. Visit the village of Somersby, an isolated and lonely hamlet deep in the Wolds of Lincolnshire, the place where he spent his boyhood. His father was rector of the church (above), and he would have wandered the isolated lanes thereabouts as a boy. The streams, the rustic bridges, the grand old houses still exist, and are little different from when he knew them. The walled garden in