I make no apology for returning to one of my all time favourite authors, the unassuming and hugely underrated Colin Watson. For a closer look at the man and his work, you can have a look at my two part study which is here. Whatever’s Been Going On In Mumblesby? was published in 1982, a year before Watson died and is the last of The Flaxborough Chronicles. This, then, is the final appearance of Detective Inspector Walter Purbright, and his earnest assistant Detective Sergeant Sydney. Love. The fun begins with this announcement in the local newspaper.

Mr Loughbury had since remarried, as they used to say, a much younger model, the undoubtedly attractive but ostensibly rather vulgar Zoe. Purbright becomes involved when, after the funeral of her husband, Zoe Loughbury, née Claypole, is discovered locked in the bathroom of The Manor House while someone seems to have set fire to the building. The fire is soon put out, but Purbright becomes aware (with the help of Miss Lucy Teatime, a local antique dealer who may not be entirely honest, but is scrupulously observant) that the late solicitor had in the house a collection of very valuable artifacts and paintings, all of which seem to have been ‘acquired’ from former clients, without a single bill of sale involved. Most bizarre among this collection is a piece of wood supposed to be a remnant of the True Cross.

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

One of Colin Watson’s more unusual achievements is that he is supposed to be one of the few people to have successfully sued Private Eye. He took exception to their writer describing his work as ‘Wodehouse without the jokes.’ He took them to court, and was awarded £750 in damages. Watson was no Wodehouse nor, I am sure, would he have claimed to be, but his jokes are not bad at all. Here. he reacts to a report from Sergeant Love:

“Love’s accounts were robbed of dramatic point somehow by his customary obliging, pleased with life expression. He would have described a public execution or a jam-making demonstration with equal cheerfulness.”

Purbright has a good but wary relationship with his boss, Chief Constable Chubb. They are discussing the vagaries in the behaviour of one of the females in the case:

“Mr Chubb waved his hand vaguely. ‘Who can say? Nervous trouble? Change of life?’ Menopause loomed as large in the chief constable’s mind as central heating and socialism.”

The owner of Mumblesby’s main restaurant has a wife who is not in the first flush of youth, but maximises her charms:

“She wore a dress of such deep cleavage that it resembled a long pair of partly drawn curtains, with a glimpse of navel at the bottom of the V, like the eye of an inquisitive neighbour, peeping out.”

As ever, Purbright’s mild manner and courtesy are totally underestimated by the criminals and schemers in and around Flaxborough. He has a steely perception which is more than a match for the rich but vulgar farmers who are up to their necks in the death of Bernadette Croll and, to show that he is no respecter of persons, he is equally merciless with the impoverished gentry. The jokes and comedy aside, for Walter Purbright justice is, indeed, blind – at least to class divisions and the county social hierarchy.

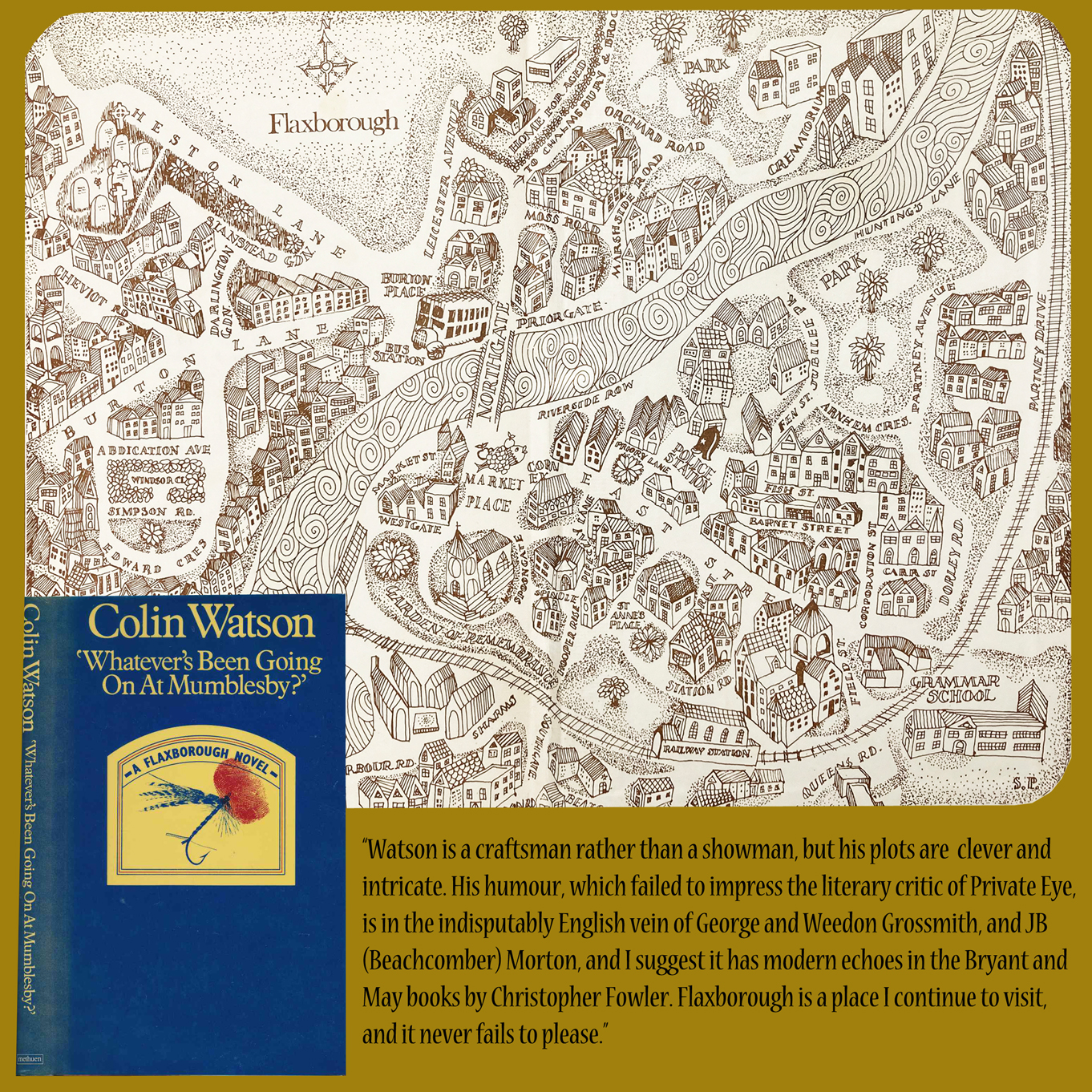

The Flaxborough novels are redolent of another time, certainly, and I suspect that they may well have been even when they were first published. Watson is a craftsman rather than a showman, but his plots are clever and intricate. His humour, which failed to impress the literary critic of Private Eye, is in the indisputably English vein of George and Weedon Grossmith, and JB (Beachcomber) Morton, and I suggest it has modern echoes in the Bryant and May books by Christopher Fowler. Flaxborough is a place I continue to visit, and it never fails to please. Finally, thanks to Peter Hannan and Stuart Radmore for the lovely map of Flaxborough used in the feature image, which was originally created by Salim Patel.

There is, perhaps, a legitimate debate to be had over what to call killings which are carried out in the name of a political cause. No-one in their right mind would label the millions of soldiers who died in the two world wars of the 20th century as murder victims. The wearing of a uniform, and the acceptance of the King’s shilling has always legitimised the act of pulling the trigger, firing the shell, or dropping the bomb.

There is, perhaps, a legitimate debate to be had over what to call killings which are carried out in the name of a political cause. No-one in their right mind would label the millions of soldiers who died in the two world wars of the 20th century as murder victims. The wearing of a uniform, and the acceptance of the King’s shilling has always legitimised the act of pulling the trigger, firing the shell, or dropping the bomb.

Just a couple of hours later, as emergency services struggled to deal with the mayhem in South Carriage Drive, the terrorists struck again. It seems barely credible that in another part of the city, life was going on as normal. Remember, though, that these were the days before mobile ‘phones and social media, the days when news was only transmitted in print, by word of mouth and on radio and television. The regimental band of The Royal Green Jackets was entertaining a small crowd clustered round the bandstand in Regent’s Park. They were playing distinctly un-martial music from the musical ‘Oliver!’ when, at 12.55 pm, a massive bomb went off beneath the bandstand. The blast was so powerful that one of the bodies was thrown onto an iron fence thirty yards away, and seven bandsmen were killed outright. They were: Warrant Officer Graham Barker, Serjeant Robert “Doc” Livingstone, Corporal Johnny McKnight, Bandsman John Heritage, Bandsman George Mesure, Bandsman Keith “Cozy” Powell, and Bandsman Larry Smith.

Just a couple of hours later, as emergency services struggled to deal with the mayhem in South Carriage Drive, the terrorists struck again. It seems barely credible that in another part of the city, life was going on as normal. Remember, though, that these were the days before mobile ‘phones and social media, the days when news was only transmitted in print, by word of mouth and on radio and television. The regimental band of The Royal Green Jackets was entertaining a small crowd clustered round the bandstand in Regent’s Park. They were playing distinctly un-martial music from the musical ‘Oliver!’ when, at 12.55 pm, a massive bomb went off beneath the bandstand. The blast was so powerful that one of the bodies was thrown onto an iron fence thirty yards away, and seven bandsmen were killed outright. They were: Warrant Officer Graham Barker, Serjeant Robert “Doc” Livingstone, Corporal Johnny McKnight, Bandsman John Heritage, Bandsman George Mesure, Bandsman Keith “Cozy” Powell, and Bandsman Larry Smith. Downey (right) may or may not have been implicated in the Hyde Park murders. Only he knows for certain. At least he had the decency to cancel a party planned in his honour when he was released. He said:

Downey (right) may or may not have been implicated in the Hyde Park murders. Only he knows for certain. At least he had the decency to cancel a party planned in his honour when he was released. He said: