The first thing to say is that the title won’t make much sense if you just randomly saw it on a shelf, but pick it up and you will see it is the first part of a trilogy, the two following novels being Skins and Kills. We meet Arran Cunningham, a young Scot. He is a Metropolitan Police officer working in Hackney, East London. Not being a Londoner, I have no idea what Hackney is like these days. I suspect it may have become more gentrified than it was in the spring of 1988. What Cunningham sees when he is walking his beat is something of a warzone. There is a large black population, mostly of Jamaican origin, and the lid is only just holding its own on a pot of simmering racial tensions, turf wars between drug gangs and a general air of despair and degeneration.

The pivotal event in the novel is a mugging (for expensive trainers) that turns into rape. The victim is a black teenager called Nadia Carrick. The attackers are a trio of young white men, led by a boy nicknamed Spider. They are unemployed, drug addicted, and live in a squat. Nadia tries to conceal the attack from her father, Stanton, but eventually he learns the true extent of her nightmare, and he seeks retribution. Stanton Carrick is an accountant, but a rather special one. His sole employer is Eldine Campbell, ostensibly a club and café owner, but actually the main drugs boss in the borough, and someone who needs his obscene profits legitimised.

Carrick is also a great friend of Arran Cunningham, who learns what has happened to Nadia. Purely by luck he saw Spider and his two chums on the night of the incident, but was unaware at the time of what had happened. Rather than use his own men to avenge Nadia’s rape, Eldine Campbell has a rather interesting solution. He has what could be called a “special relationship’ with a group of police officers, led by Detective Chief Inspector Vince Girvan, and he assigns them the task of dealing with with the perpetrators.

Meanwhile, Girvan has taken a special interest in Arran Cunningham, and assigns him to plain clothes duties, the first of which is to be a part of the crew eliminating Spider and his cronies. In at the deep end, he is not involved with their abduction, but is brought in as the trio are executed in a particularly grisly – but some might say appropriate – fashion. There is problem, though, and it is a big one. He recognises Spider’s two accomplices, but the third man is just someone random, and totally innocent of anything involving Nadia.

The three bodies are disposed of in the traditional fashion via a scrapyard crushing machine, but Cunningham is in a corner. His dilemma is intensified when his immediate boss, DI Kat Skeldon, aware that there is a police force within a police force operating, enrols him to be ‘on the side of the angels.’ As if things couldn’t become more complex, Cunningham learns that Stanton Carrick is dying of cancer.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

The author (left) was a long-serving officer in the Met, and so we can take it as read that his descriptions of their day-to-day procedures are authentic. In Arran Cunningham, he has created a perfectly credible anti-hero. I am not entirely sure that he is someone I would trust with my life, but I eagerly await the next instalment of his career. Hunts is published by Caprington Press and will be available on 8th January.

On his trail is a grotesque cartoon of a copper – DCI Dave Hicks. He lives at home with his dear old mum, has a prodigious appetite for her home-cooked food, is something of a media whore (he does love his press conferences) and has a shaky grasp of English usage, mangling idioms like a 1980s version of Mrs Malaprop.

On his trail is a grotesque cartoon of a copper – DCI Dave Hicks. He lives at home with his dear old mum, has a prodigious appetite for her home-cooked food, is something of a media whore (he does love his press conferences) and has a shaky grasp of English usage, mangling idioms like a 1980s version of Mrs Malaprop. “A fuchsia -pink shirt with outsize wing collar, over-tight lime green denim jeans, a brand new squeaky-clean leather jacket and, just for good measure, a black beret with white trim.”

“A fuchsia -pink shirt with outsize wing collar, over-tight lime green denim jeans, a brand new squeaky-clean leather jacket and, just for good measure, a black beret with white trim.”

This has the most seriously sinister beginning of any crime novel I have read in years. DI Henry Hobbes (of whom more presently) is summoned by his Sergeant to Bridlemere, a rambling Edwardian house in suburban London, where an elderly man has apparently committed suicide. Corpse – tick. Nearly empty bottle of vodka – tick. Sleeping pills on the nearby table – tick. Hobbes is not best pleased at his time being wasted, but the observant Meg Latimer has a couple of rabbits in her hat. One rabbit rolls up the dead man’s shirt to reveal some rather nasty knife cuts, and the other leads Hobbes on a tour round the house, where he discovers identical sets of women’s clothing, all laid out formally, and each with gashes in the midriff area, stained red. Sometimes the stains are actual blood, but others are as banal as paint and tomato sauce.

This has the most seriously sinister beginning of any crime novel I have read in years. DI Henry Hobbes (of whom more presently) is summoned by his Sergeant to Bridlemere, a rambling Edwardian house in suburban London, where an elderly man has apparently committed suicide. Corpse – tick. Nearly empty bottle of vodka – tick. Sleeping pills on the nearby table – tick. Hobbes is not best pleased at his time being wasted, but the observant Meg Latimer has a couple of rabbits in her hat. One rabbit rolls up the dead man’s shirt to reveal some rather nasty knife cuts, and the other leads Hobbes on a tour round the house, where he discovers identical sets of women’s clothing, all laid out formally, and each with gashes in the midriff area, stained red. Sometimes the stains are actual blood, but others are as banal as paint and tomato sauce.

My verdict on House With No Doors? In a nutshell, brilliant – a tour de force. Jeff Noon (right) has taken the humble police procedural, blended in a genuinely frightening psychological element, added a layer of human corruption and, finally, seasoned the dish with a piquant dash of insanity. On a purely narrative level, he also includes one of the most daring and astonishing final plot twists I have read in many a long year.

My verdict on House With No Doors? In a nutshell, brilliant – a tour de force. Jeff Noon (right) has taken the humble police procedural, blended in a genuinely frightening psychological element, added a layer of human corruption and, finally, seasoned the dish with a piquant dash of insanity. On a purely narrative level, he also includes one of the most daring and astonishing final plot twists I have read in many a long year.

This is a curious and quite unsettling book which does not fit comfortably into any crime fiction pigeon-hole. I don’t want to burden it with a flattering comparison with which other readers may disagree, but it did remind me of John Fowles’s intriguing and mystifying cult novel from the 1960s, The Magus. I am showing my age here and, OK, The Gilded Ones is about a quarter of the length of The Magus, it’s set in 1980s London rather than a Greek island and the needle on the Hanky Panky Meter barely flickers. However we do have a slightly ingenuous central character who serves a charismatic, powerful and magisterial master and there is a nagging sense that, as readers, we are having the wool pulled over our eyes. There is also an uneasy feeling of dislocated reality and powerful sensory squeezes, particularly of sound and smell. Author Brooke Fieldhouse (left) even gives us female twins who are not, sadly, as desirable as Lily and Rose de Seitas in the Fowles novel.

This is a curious and quite unsettling book which does not fit comfortably into any crime fiction pigeon-hole. I don’t want to burden it with a flattering comparison with which other readers may disagree, but it did remind me of John Fowles’s intriguing and mystifying cult novel from the 1960s, The Magus. I am showing my age here and, OK, The Gilded Ones is about a quarter of the length of The Magus, it’s set in 1980s London rather than a Greek island and the needle on the Hanky Panky Meter barely flickers. However we do have a slightly ingenuous central character who serves a charismatic, powerful and magisterial master and there is a nagging sense that, as readers, we are having the wool pulled over our eyes. There is also an uneasy feeling of dislocated reality and powerful sensory squeezes, particularly of sound and smell. Author Brooke Fieldhouse (left) even gives us female twins who are not, sadly, as desirable as Lily and Rose de Seitas in the Fowles novel. Lloyd Lewis is the Magus-like figure. He is so thumpingly male that you can almost smell him, and he rules those around him, with one exception, with an almost feral ferocity. So who are ‘those around him’? Ever present psychologically, but eternally absent physically, is his late wife Freia, the subject of Pulse’s dream. Martinique is Patrick’s girlfriend, and loitering in the background are his children, step-child and office gofer Lauren. Lauren, who has “thousand-year-old eyes”, is of the English nobility, but quite what she is doing in the Georgian townhouse we only learn at the end of the book. The one person to whom Patrick defers is his Sicilian friend Falco. Equalling the Englishman’s sense of menace, the sinister Falco appears briefly but is, nonetheless, memorable.

Lloyd Lewis is the Magus-like figure. He is so thumpingly male that you can almost smell him, and he rules those around him, with one exception, with an almost feral ferocity. So who are ‘those around him’? Ever present psychologically, but eternally absent physically, is his late wife Freia, the subject of Pulse’s dream. Martinique is Patrick’s girlfriend, and loitering in the background are his children, step-child and office gofer Lauren. Lauren, who has “thousand-year-old eyes”, is of the English nobility, but quite what she is doing in the Georgian townhouse we only learn at the end of the book. The one person to whom Patrick defers is his Sicilian friend Falco. Equalling the Englishman’s sense of menace, the sinister Falco appears briefly but is, nonetheless, memorable.

It is 1987, and a bitterly cold winter night in New Jersey. In a rambling Queen Anne-style house in West Windsor, a man is found dead, battered to death and lying in a pool of his own blood. The corpse is that of a successful but controversial academic from Princeton, Professor Joseph Wieder. For all his erudition and his insights into the human brain – particularly the workings of memory – he is still very dead. The police dutifully stumble around in the snow, interviewing those who knew the dead man, but they fail to find anyone without a decent alibi, let alone a suspect who stood to gain substantially from his death.

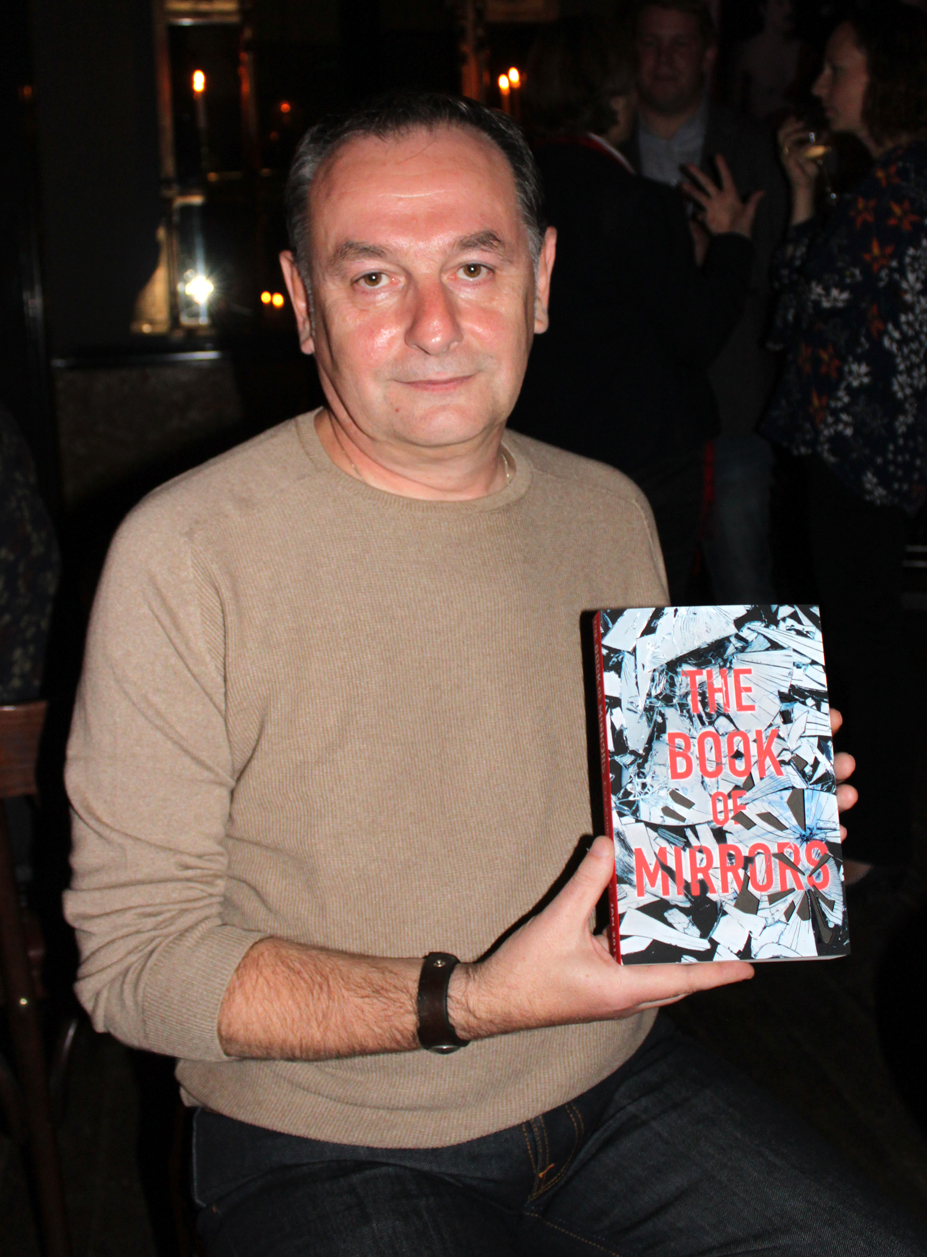

It is 1987, and a bitterly cold winter night in New Jersey. In a rambling Queen Anne-style house in West Windsor, a man is found dead, battered to death and lying in a pool of his own blood. The corpse is that of a successful but controversial academic from Princeton, Professor Joseph Wieder. For all his erudition and his insights into the human brain – particularly the workings of memory – he is still very dead. The police dutifully stumble around in the snow, interviewing those who knew the dead man, but they fail to find anyone without a decent alibi, let alone a suspect who stood to gain substantially from his death. We first learn of Wieder’s violent demise in a roundabout way. A literary agent, Peter Katz, is working his way through emails from hopeful authors, and consigning most of them to the trash icon, when his attention is grabbed by a submission from a man called Richard Flynn. Katz prints out the sample chapters of Flynn’s book and sits down to read them. He is hooked. Two hours fly past, and Katz realises that he has a possible best seller in his hands, but he is unsure if the book is a true crime confession, or a novel. So, what did Flynn have to say?

We first learn of Wieder’s violent demise in a roundabout way. A literary agent, Peter Katz, is working his way through emails from hopeful authors, and consigning most of them to the trash icon, when his attention is grabbed by a submission from a man called Richard Flynn. Katz prints out the sample chapters of Flynn’s book and sits down to read them. He is hooked. Two hours fly past, and Katz realises that he has a possible best seller in his hands, but he is unsure if the book is a true crime confession, or a novel. So, what did Flynn have to say? There is a very satisfying sense of a torch being handed from one runner to another, and it is during Freeman’s leg of the journey that we find out the truth of what really happened to Joseph Wieder. Or do we? Changing the metaphor, Chirovici tells us that we have been in one of those fairground attractions which involves walking in front of distorting mirrors. He says;

There is a very satisfying sense of a torch being handed from one runner to another, and it is during Freeman’s leg of the journey that we find out the truth of what really happened to Joseph Wieder. Or do we? Changing the metaphor, Chirovici tells us that we have been in one of those fairground attractions which involves walking in front of distorting mirrors. He says;