The book is set in the Britain of 1949. A strange place and no mistake. Strange? We had won the war, hadn’t we? To the victor the spoils? The reality is very different. The country is spent. Exhausted. Food and comfort are as scarce as they were six years earlier. Clement Attlee’s Labour government is trying to rebuild a country brought to its knees by five years of bombs, rationing, death and destruction. International politics and diplomacy are chaotic. America is, on the one hand, busy rounding up the less egregious former Nazi scientists and intelligence agents to work for them while, on the other, fiercely fighting the growing influence of the not-so-avuncular ‘Uncle Joe’ Stalin.

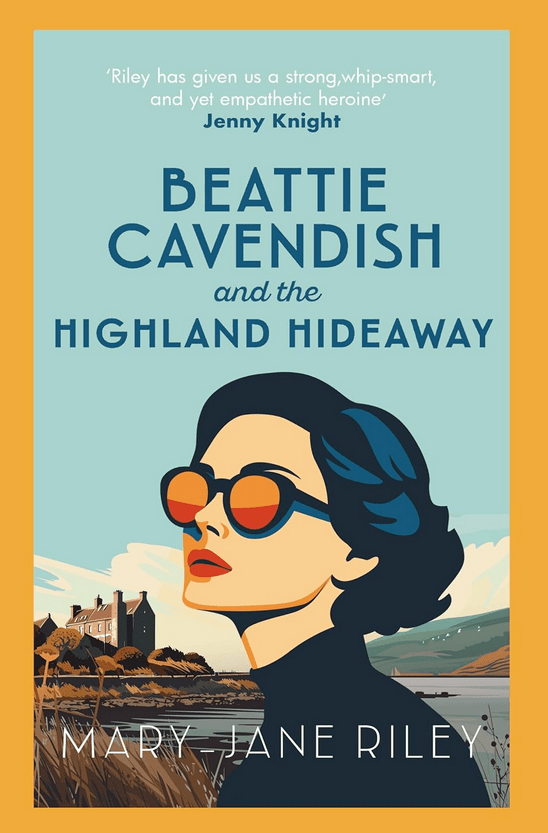

Caught up in this is British intelligence agent Beattie Cavendish. She works for the embryonic ‘listening agency’ GCHQ, and is sent up to Kilbray in the Scottish Highlands, posing as a secretarial instructor, to investigate a suspected leaking of information to the Russians. Readers new to the series will be unaware of Beattie’s recent history, of her time with the resistance in Occupied France, of her older brother, missing presumed dead, and her relationship with the battle-scarred Irish private investigator Corrigan. Rest assured, the author inserts these ‘catch-ups’ into the story smoothly and without disrupting the drive of the narrative.

When she arrives at Kilbray, Beattie expects to be reunited with her paternal uncle Howard, something of a family black sheep, but not unconnected with the intelligence community and international subterfuge. When she arrives at his loch-side cottage, he is not there. It is, however, something of a Marie Celeste situation. Whisky glasses are on the table, and food is in the cupboards. Also AWOL is Commander Henry Swaffer, the officer in charge of Kilbray. Local rumour has it that the thrice-married gentleman has gone on a fling with his latest girlfriend, a young German woman called Klara. That theory is severely tested when a dog-walker (where would crime fiction be without them?) finds Swaffer’s body washed up on the beach. It appears he has been strangled and his body cast into the waves.

Swaffer’s German friend Klara makes herself known to Beattie, but is then fatally stabbed in broad daylight in what appears to be a professional hit, and there is still no sign of uncle Howard. Beattie senses that the answers may lie in a mysterious establishment at Balgowrie, a place known as ‘the cooler’. During the war it was a sinister mix of refuge and prison, a place where agents who had lost their nerve, or escaped from failed missions, were confined. Beattie and Corrigan finally break into Balgowrie, and their invasion precipitates a violent and exciting dénouement.

Ann-Marie Riley also hints at the eternally fraught relationship between Britain and the Irish Republic. Thousands of men from southern Ireland gave their lives for Britain in The Great War, but by 1939, Ireland was resolutely neutral. Or was it? In the real world, men like Corrigan who had fought against the Nazis would be subsequently marginalised and denied pensions. Post 1945, committed Nazis like Célestin Lainé and Otto Skorzeny would be welcomed by the Irish state, and sheltered from the retribution facing fellow former Nazis. Riley isn’t trying to right ancient wrongs. She is merely setting out the sometimes unpleasant aspects of history and they actually happened.

You would be wrong to assume from the alliterative title and the cover graphics that this is a cosy crime story. Yes, Beattie is a perfect ladies’ book-reading-circle heroine. Certainly, there are occasional ‘Boys’ Own’ elements to the story, and perhaps the damaged PI Corrigan – who won his medals and his scares in the sheer hell of Monte Casino – can sometimes be too gung-ho for his own good, but Mary-Jane Riley takes a long hard look at a Britain struggling for identity, self-preservation, and searching for old certainties that have been blown away by the strong winds of a brutal post-war world. Beattie Cavendish and the Highland Hideaway will be published by Allison & Busby on 19th February.

Fancy a mint hardback copy of this book? Make a note of this code, and follow me on social media to enter the competition. UK addresses only, closes 10.00pm 22nd February.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it. Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

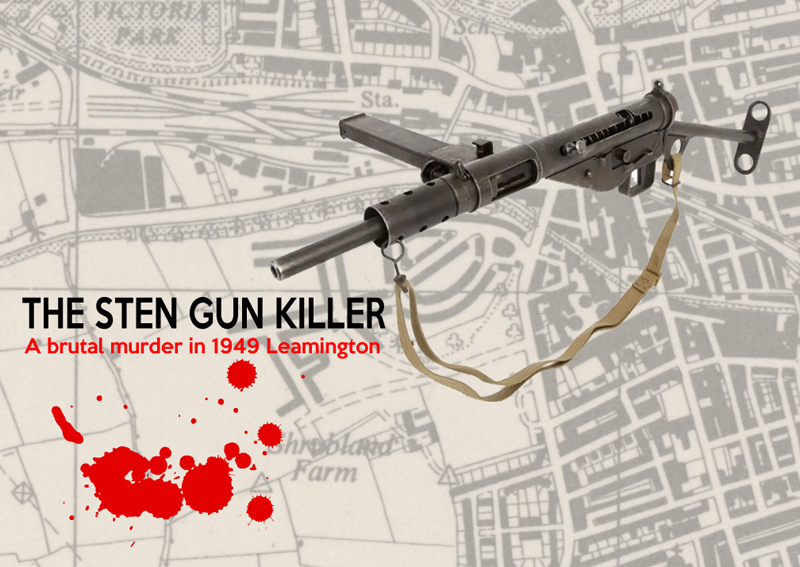

Swadling Street in Leamington is an unassuming thoroughfare, with houses which were built on the old Shrubland Estate between the wars. It was named after a Leamington councillor of the 1920s, and in 1931 it boasted twenty addresses. In January 1949, number 6 was occupied by Edward Sullivan. A 49 year-old Irishman and father of six children – three sons and three daughters – he worked as a builder’s labourer. Known to his mates – inevitably – as Paddy – he was working on a council house building project on Westlea Road, which was another between-wars development on what had been the Shrubland Estate.

Swadling Street in Leamington is an unassuming thoroughfare, with houses which were built on the old Shrubland Estate between the wars. It was named after a Leamington councillor of the 1920s, and in 1931 it boasted twenty addresses. In January 1949, number 6 was occupied by Edward Sullivan. A 49 year-old Irishman and father of six children – three sons and three daughters – he worked as a builder’s labourer. Known to his mates – inevitably – as Paddy – he was working on a council house building project on Westlea Road, which was another between-wars development on what had been the Shrubland Estate.

rcher served his country with distinction in the war, fighting his way up the spine of Italy, watching his buddies die hard, and wondering about the ‘just cause’ that has trained him to shoot, throttle, stab and maim fellow human beings while, at the same time, preventing him from being at the deathbeds of both parents.

rcher served his country with distinction in the war, fighting his way up the spine of Italy, watching his buddies die hard, and wondering about the ‘just cause’ that has trained him to shoot, throttle, stab and maim fellow human beings while, at the same time, preventing him from being at the deathbeds of both parents. Wearing a cheap suit, regarded as trash by the local people, and with every cause to feel bitter, Archer checks into the Derby Hotel and contemplates the future. His immediate task is to check in with his Probation Officer, Ernestine Crabtree. Quietly impressed by her demeanour – and her physical charm – Archer goes, in spite of his parole restrictions, for a drink in a local bar, The Cat’s Meow

Wearing a cheap suit, regarded as trash by the local people, and with every cause to feel bitter, Archer checks into the Derby Hotel and contemplates the future. His immediate task is to check in with his Probation Officer, Ernestine Crabtree. Quietly impressed by her demeanour – and her physical charm – Archer goes, in spite of his parole restrictions, for a drink in a local bar, The Cat’s Meow ven before Lucas Tuttle answers the door to Archer’s knock by pointing a cocked Remington shotgun at his unwelcome visitor, Archer has learned that the floozie on Pittleman’s arm in the bar is none other than Jackie, Tuttle’s estranged daughter. Archer finds the coveted motor car hidden away on Tuttle’s ranch, but it has been deliberately torched. Cursing his involvement in this blood feud, Archer’s equilibrium and freedom both take a severe knock when Pittleman’s body is found in a bedroom just along the floor from Archer’s room in The Derby. Thrown into the cells as the obvious suspect, Archer is released when he meets up with Irving Shaw – a serious and competent detective – and convinces him of his innocence.

ven before Lucas Tuttle answers the door to Archer’s knock by pointing a cocked Remington shotgun at his unwelcome visitor, Archer has learned that the floozie on Pittleman’s arm in the bar is none other than Jackie, Tuttle’s estranged daughter. Archer finds the coveted motor car hidden away on Tuttle’s ranch, but it has been deliberately torched. Cursing his involvement in this blood feud, Archer’s equilibrium and freedom both take a severe knock when Pittleman’s body is found in a bedroom just along the floor from Archer’s room in The Derby. Thrown into the cells as the obvious suspect, Archer is released when he meets up with Irving Shaw – a serious and competent detective – and convinces him of his innocence. Pretty much left on his own to solve the case after a violent attempt to silence Jackie, Archer has to summon up very ounce of his military experience and his innate common sense to put himself beyond the reach of the hangman’s noose.

Pretty much left on his own to solve the case after a violent attempt to silence Jackie, Archer has to summon up very ounce of his military experience and his innate common sense to put himself beyond the reach of the hangman’s noose.