John Russell is an Anglo American journalist turned spy. His problem is that he has spied for too many different countries. He has spied for the Russians, the Nazis, the British and the Americans – and they all have a piece of him. In his heart of hearts he is a pre-Stalin communist. Once a member of the party, he is a man who once believed in the promise of genuine socialism.

December 1945 finds him in London with his long term girlfriend Effie Koenen, his son by his marriage to a wife long since dead, and Effie’s sister. He is basically a puppet waiting for the next tug on his strings. This time it comes from the Russians. Such is Stalin’s power and reach in the postwar world that he can easily persuade his allies to terminate Russell’s temporary haven in London, and so it is that Russell and Effie are forced to return to the shattered remains of Berlin.

Effie was a considerable star in the pre-war film world and is anxious to resume her career. For Russell it is a question literally of life and death. If he does not follow the instructions of the NKVD he knows that his life will not be worth living, nor those of Effie or his son Paul. Paul fought in the Wehrmacht in the dying days of the war but has been allowed to re-settle in London as part of the Russian deal for Russell’s continued cooperation.

One historical issue that runs through the book is the plight of Europe’s Jews. Despite survivors living in Berlin being given special victim status by the occupying administration, and thus receiving better rations, further afield many Jews still found themselves homeless and unwanted. The British are determined to limit the number of Jews heading to the new land in Arab Palestine. The Russians are indifferent and the Americans are torn between support for the British and an awareness of the voting power of Jewish American citizens.

Across central Europe there are several Jewish organisations determined to avenge the deaths of their fellow citizens, by whatever means necessary. Russell meets a young man called Michael who is in one such group.

Michael smiled for the first time and it lit up his face.

“Do you know Psalm 94?” he asked.

“Not that I remember.”

“He will repay them for their iniquity and wipe them out for their wickedness. The Lord our God will wipe them out.”

“The Nazis I assume? So if God has them in his sights, where do you come in? Are you God’s instruments?”

“Not at all. if there is a God he has clearly abandoned the Jews. We will do the work that he should have done.”

David Downing (left), writing this book in 2012, was obviously well aware of how things have played out in our own times, but he has Russell reunited with a young Jew who he had helped escape Germany years earlier.

“And I’ll tell you something else,”. Albert said. “I understand why the Poles are expelling the Germans from their new territories, and I understand why they are making it impossible for the Jews to return. If my friends and I have our way the Arabs will all be expelled from Palestine. Anything else is just stirring up trouble for the future.”

“That will put a bit of a strain on the worlds sympathy, don’t you think?”

“Once we have the land we can do without the sympathy.”

Russell’s sense of world weariness and and the depth of his cynicism about those who employ him does not prevent him from being a compassionate man. In order to file a marketable story with his London agent, Russell embeds himself with what could be called a gang of people smugglers, except the people that are being smuggled are Jews desperate to get away from Europe and start a new life in Palestine. The route involves a long and arduous trek – literally across mountains and rivers in – order to get to Italy and then to the Mediterranean Sea. There is one bitterly ironic scene where, on the way, Russell meets up with a man who he knows is a former SS officer. The man is with his young son and Russell promises not to betray them to the Jews, basically because of the young boy. In an awful reversal of what happened to so many Jews years earlier, the pair are identified as non Jews because they are uncircumcised. Russell cannot prevent the father being gunned down; neither can he persuade the boy to leave his father’s body as the convoy moves on.

In another sub plot of the book, Russell tries to locate two missing Jewish people. One is very much close and personal to him and Effie. Earlier in the war Effie had given a home to Rosa, an apparently orphaned Jewish girl. She has now taken Rosa as the child she now knows she will probably never have, and Rosa has gone with them to England. However, at the back of Effie’s mind is that if either of Rosa’s parents should be discovered alive, this will pose a great problem should they wish to reclaim their daughter. Using the same sources – mostly meticulous Nazi bureaucratic records of who was sent where – Russell also tries to discover the fate of a young Silesian Jew called Miriam who we met in an earlier book in this excellent series. (Click the link below for more information)

https://fullybooked2017.com/tag/david-downing/

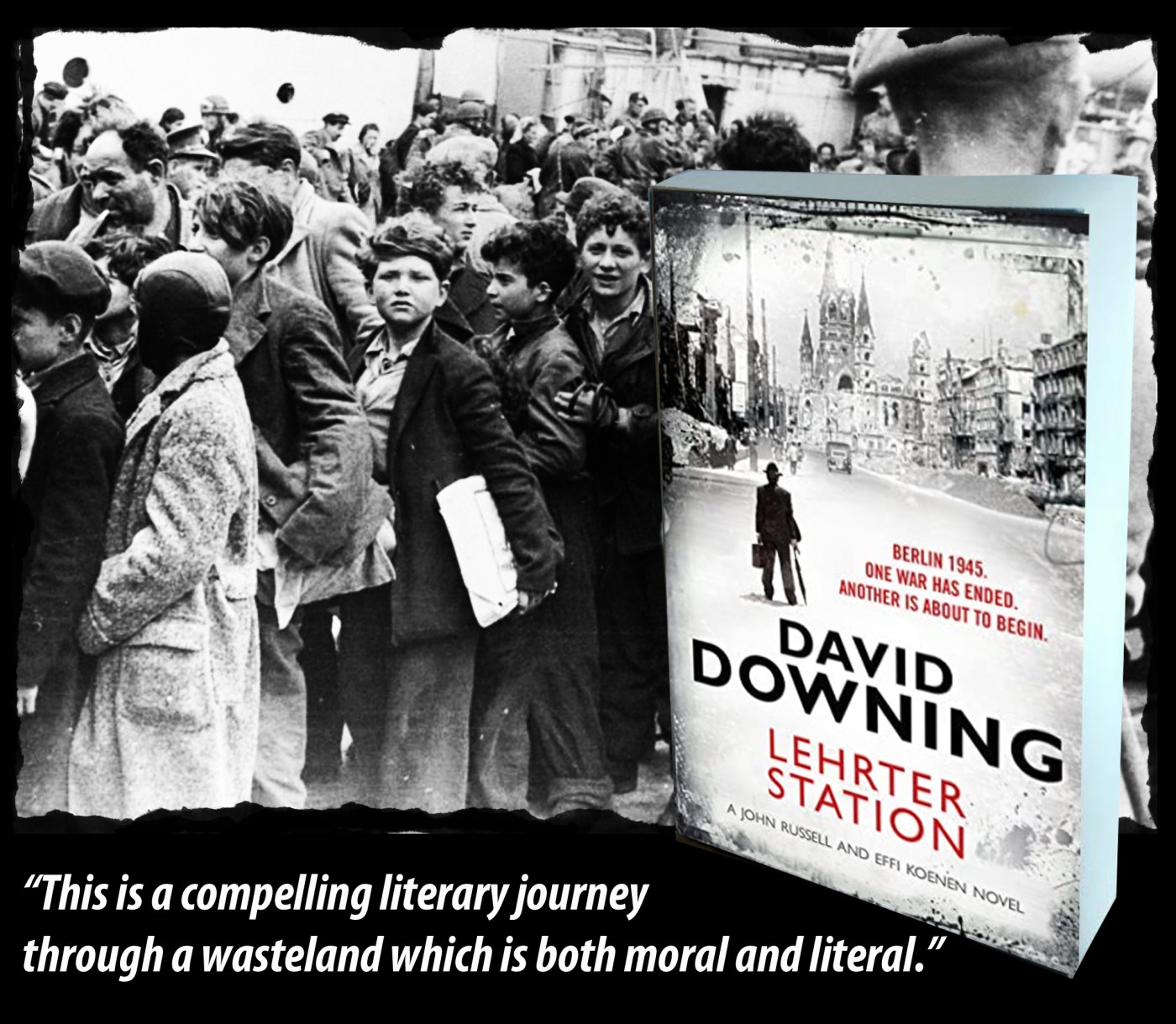

With a mixture of luck, cunning – and favours from friends – Russell manages to survive the t. ands of his Russian minders goes fatally wrong. By the end of the book Russell has peeled back layer after layer of spectacularly evil deeds committed by all parties and nationalities, but somehow his personal integrity – and that of Effie – survive. This is a compelling literary journey through a wasteland which is both moral and literal.

By the autumn of 1944, German forces had been pushed out of France and were being systematically overwhelmed by the Red Army in the east. The allies had control of the Channel coast, but the Germans had effectively wrecked the French ports. Antwerp, however, had been taken more or less intact, and when the Germans had been removed from their strong-points controlling the estuary of the River Scheldt, the Belgian port became a massive conduit for the arrival of men, machines and supplies for the Allies.

By the autumn of 1944, German forces had been pushed out of France and were being systematically overwhelmed by the Red Army in the east. The allies had control of the Channel coast, but the Germans had effectively wrecked the French ports. Antwerp, however, had been taken more or less intact, and when the Germans had been removed from their strong-points controlling the estuary of the River Scheldt, the Belgian port became a massive conduit for the arrival of men, machines and supplies for the Allies. It is one of the great paradoxes of WW2 that on the ground, at least, the Germans had the best guns, the best artillery and the best tanks. The problem was that although the formidable Panzers were easily able to overcome the relatively underpowered Sherman tanks used by the allies, the German vehicles were high maintenance and, some would say, over-engineered. The ubiquitous Shermans were rolling off the production lines in their thousands, while the formidable Tigers and Panthers – when they developed a fault – were fiendishly difficult to repair or cannibalise. Caddick-Adams (right) also reminds us how well-fed and supplied the American GIs were compared with their German foes. In one particularly eloquent passage, he tells us of the utter joy felt by a unit of Volksgrenadiers when they seized a supply of American rations. When their own kitchen unit eventually reached their position, the cooks and their containers of watery stew were given very short shrift.

It is one of the great paradoxes of WW2 that on the ground, at least, the Germans had the best guns, the best artillery and the best tanks. The problem was that although the formidable Panzers were easily able to overcome the relatively underpowered Sherman tanks used by the allies, the German vehicles were high maintenance and, some would say, over-engineered. The ubiquitous Shermans were rolling off the production lines in their thousands, while the formidable Tigers and Panthers – when they developed a fault – were fiendishly difficult to repair or cannibalise. Caddick-Adams (right) also reminds us how well-fed and supplied the American GIs were compared with their German foes. In one particularly eloquent passage, he tells us of the utter joy felt by a unit of Volksgrenadiers when they seized a supply of American rations. When their own kitchen unit eventually reached their position, the cooks and their containers of watery stew were given very short shrift.