The year of 1926 was not a particularly momentous one for Wisbech.The canal was officially closed, the first cricket match was played on the Harecroft Road ground, and greyhound racing came to South Brink. For one Wisbech family, the year would bring a trauma that would haunt them for the rest of their lives

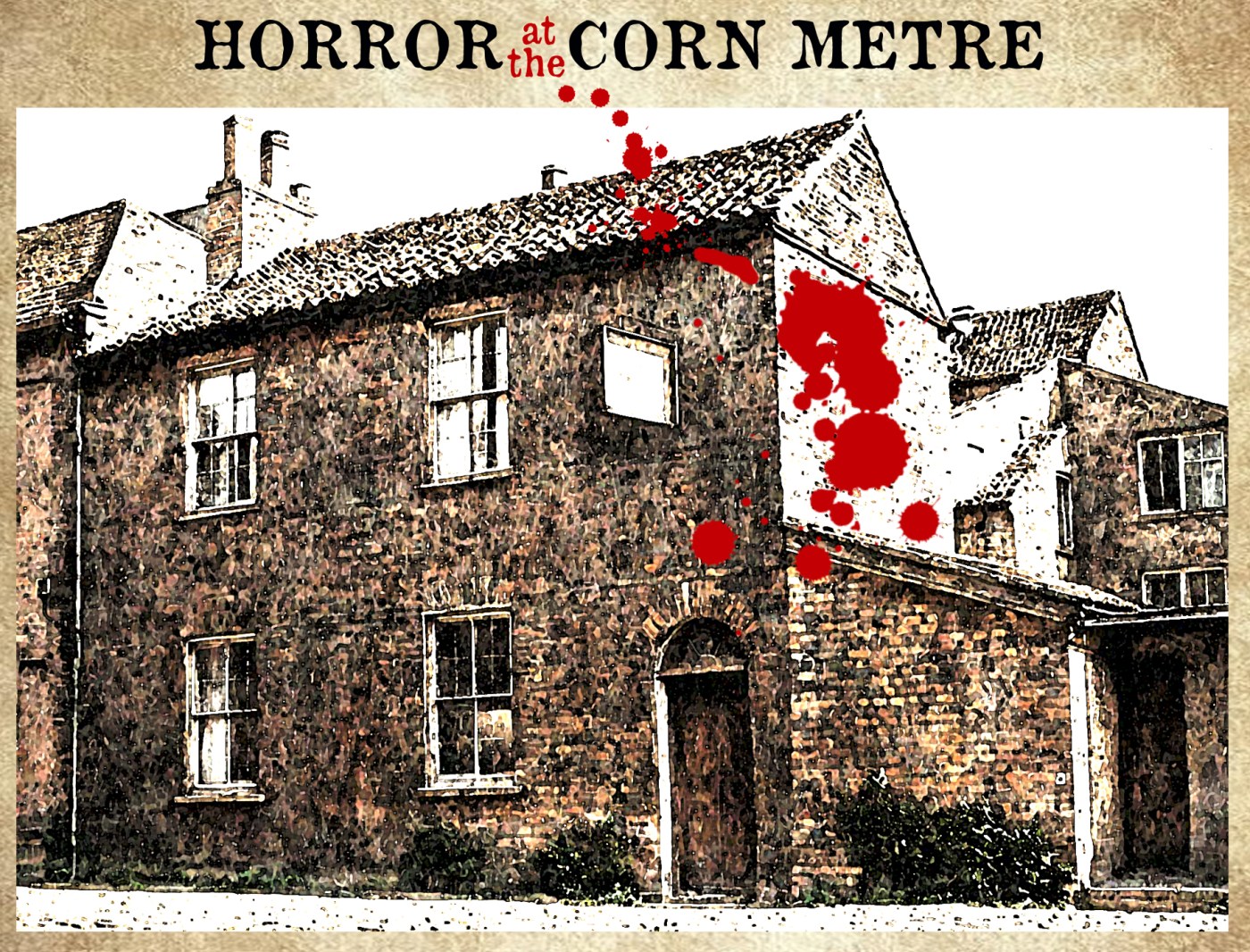

The Corn Metre Inn, like dozens of other pubs from Wisbech’s history, is long gone. It had two entrances, one more or less opposite Nixon’s woodyard on North End, and the other facing the river on West Parade. The name? A Corn Metre was a very important person, back in the day. He was basically a weights and measures inspector employed by markets and auctioneers to ensure that no-one was cheating the customers.

In 1926, the landlord of the Corn Metre was Francis William Noble. He was not a Wisbech man, having been born in Shoreditch, London in 1885. He had met and married his wife Edith Elizabeth (née Bradley) in nearby West Ham in 1907. Noble volunteered for service in The Great War, and survived. By 1910 the couple had moved to Wisbech.

The 1921 census tells us that the family was living at 73 Cannon Street, that Noble was a warehouseman for Balding and Mansell, printers, and that living in the house were Edith Violet Noble (12), Phyllis Eleanor Noble (9) and Francis William Noble (6). Another daughter, Margaret Doris was born in 1923, and by 1926 the family had moved in as tenants of The Corn Metre Inn. A local newspaper reported on the events of Tuesday 15th June:

What they saw was truly horrendous. Propped up on the bed was Mrs Noble, covered in blood with terrible wounds to the throat. But beside the bed was something far worse. In a cot was little Peggy Noble. And her head had been almost severed from her body. She was quite clearly dead. The police were fetched, and then a doctor. Mrs Noble was still alive, and was rushed to the North Cambs Hospital, where she died on the Wednesday Evening.

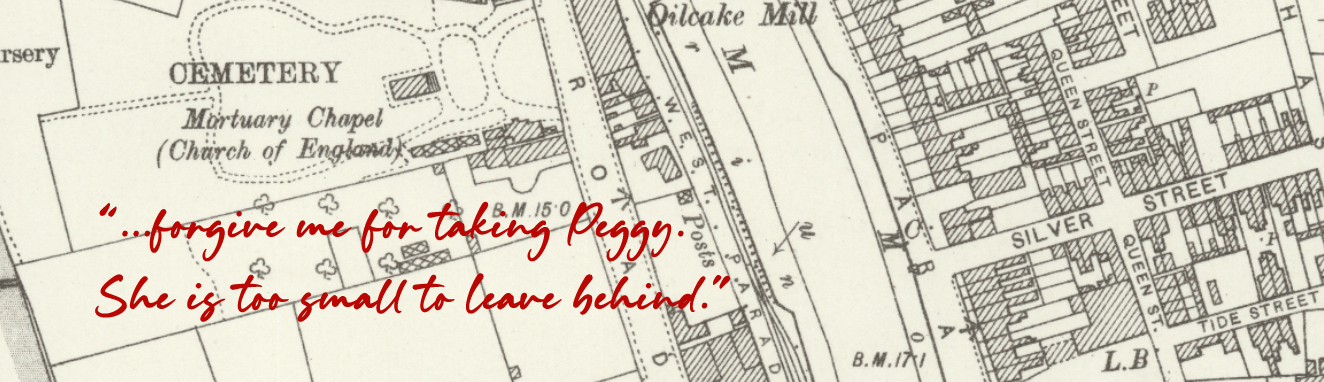

I suppose that the treatment and awareness of mental health issues has advanced since 1926. It must have, mustn’t it? I am reminded of the tragic murder/suicide In Wimblington in 1896 (details here) when a distraught mother killed herself and her four children. Sadly, there are cases today where mental health treatment is frequently misguided and inadequate. In 2023 Nottingham killer Valdo Calocane was a patient of the local mental health trust. He killed three people in a psychotic attack. There was talk, in 1926, that Edith was ‘unwell’ and that neighbours had been looking in on her. The last note written by Edith is chilling, and is clearly the work of a woman in distress. It was in some ways, however, crystal clear, and written by someone who was aware of the consequences of what she was about to do.

So many unanswered questions. So many things we will never know. Why did she think that Peggy was too young to survive with husband Francis and the other children? It is also revealing that she referred to the 8 year-old boy as ‘Son’, rather than his given name, Francis.

For reasons that can be imagined Francis Noble had had enough of Wisbech, because records show that in February 1928 he remarried, in Rochester His bride was a widow, Beatrice Emily Gadd. In July of that same year, Beatrice gave birth to a son, Peter Eddie. As the Americans say, ‘do the math”.

It is not for me, or any modern commentator to cast blame. Three things stand out, however. Firstly, the three surviving children left Wisbech as soon as they were able, and each appeared to have led perfectly ordinary lives in other parts of the country. Second, Francis Noble, within months of the terrible event at The Corn Metre had left the town, and impregnated another woman who, to be fair, he then married. Thirdly – and this part of the story will haunt me for a long time – poor little Margaret ‘Peggy’ Noble was so savagely cut with the razor that her spinal cord was severed. The coroner, in measured words, recorded that her body bore signs of a violent struggle. What kind of anger, despair and rage fuelled the assault on that little girl? And what was the cause?

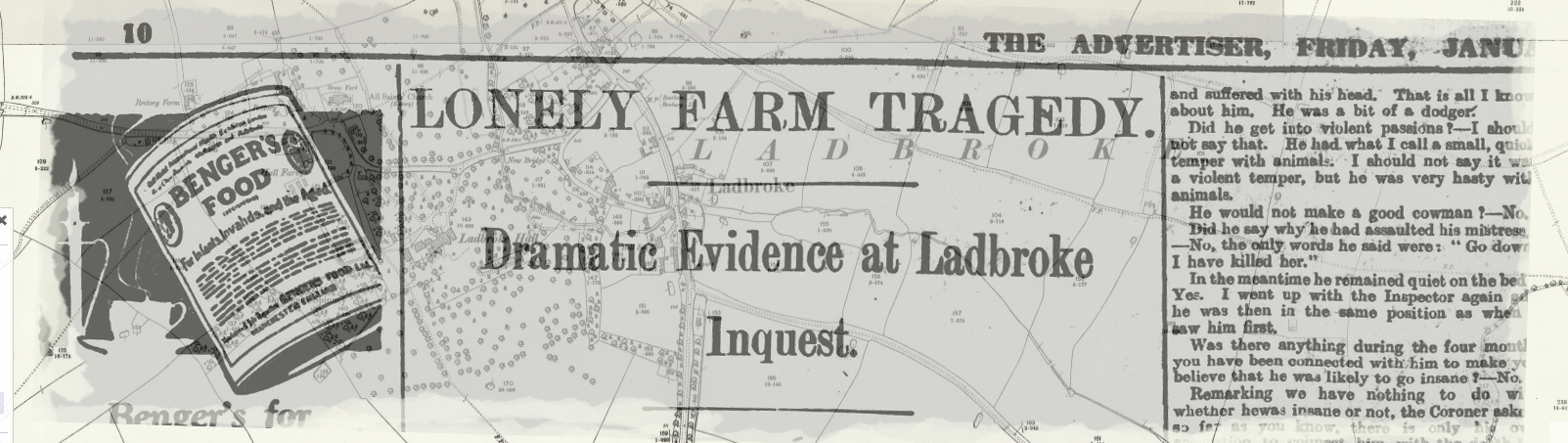

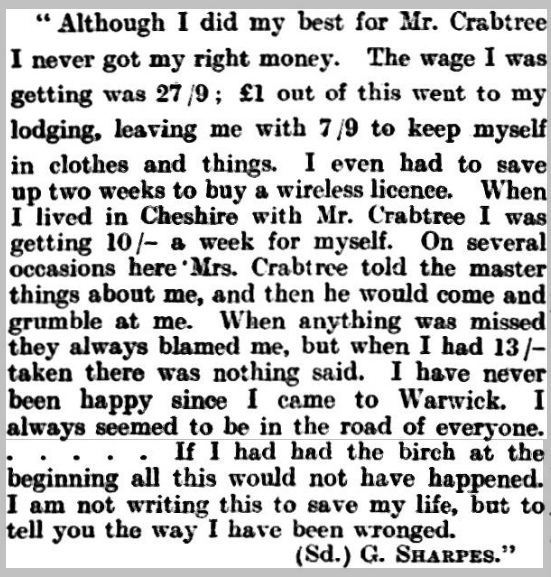

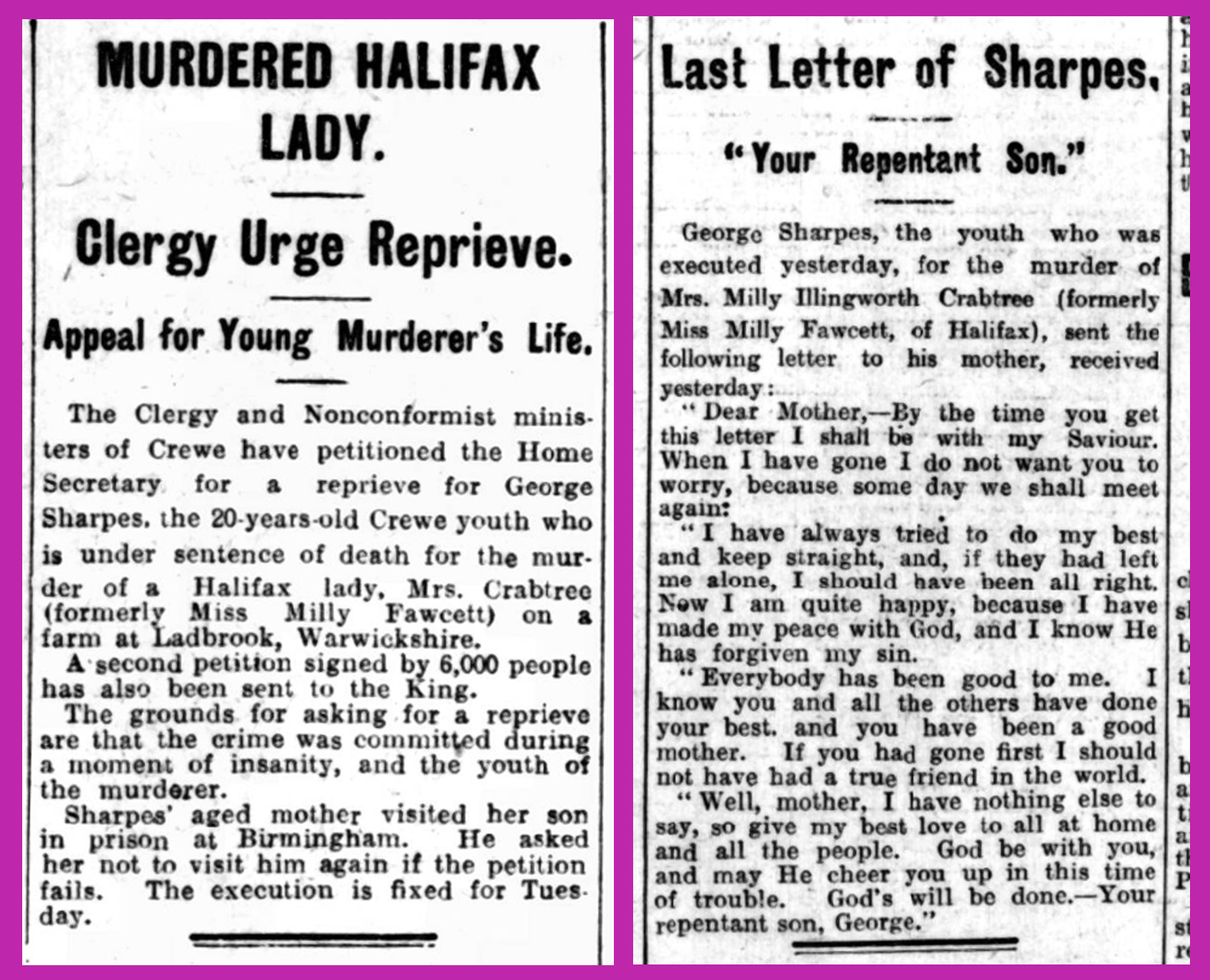

SO FAR – On January 13th 1926, Milly Crabtree, 25 year-old wife of Cecl Crabtree, is found battered to death at their home, Manor Farm in Ladbroke. 19 year-old George Sharpes is arrested for her murder. As is the way with these, things, the wheels of justice turn very slowly, and it was February before Sharpes came to face magistrates in Southam. The courtroom, normally used as a cinema (pictured above), was packed, and the onlookers were spellbound as a confession from George Sharpes was read to the court.

SO FAR – On January 13th 1926, Milly Crabtree, 25 year-old wife of Cecl Crabtree, is found battered to death at their home, Manor Farm in Ladbroke. 19 year-old George Sharpes is arrested for her murder. As is the way with these, things, the wheels of justice turn very slowly, and it was February before Sharpes came to face magistrates in Southam. The courtroom, normally used as a cinema (pictured above), was packed, and the onlookers were spellbound as a confession from George Sharpes was read to the court.

The magistrates wasted little time in stating that George Sharpes had a serious case to answer, and the case was moved on to be examined at the March Assizes in Warwick. The case was presided over by Mr Justice Shearman. The only possible line for the defence to take was that Sharpes was insane at the time at the time he committed the murder, and Sharpes’s mother was produced to state that her son had suffered an unfortunate childhood. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, however. Rejecting the claims that George Sharpes was insane, the judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death. The execution was fixed for April and, as was almost always the case, a petition was set up to ask for clemency. The case was taken to appeal, in front of Lord Chief Justice Avory, who was perhaps not the most welcome choice for Sharpes’s defence team. Avory, a notorious “hanging judge”, had been memorably described:

The magistrates wasted little time in stating that George Sharpes had a serious case to answer, and the case was moved on to be examined at the March Assizes in Warwick. The case was presided over by Mr Justice Shearman. The only possible line for the defence to take was that Sharpes was insane at the time at the time he committed the murder, and Sharpes’s mother was produced to state that her son had suffered an unfortunate childhood. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, however. Rejecting the claims that George Sharpes was insane, the judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death. The execution was fixed for April and, as was almost always the case, a petition was set up to ask for clemency. The case was taken to appeal, in front of Lord Chief Justice Avory, who was perhaps not the most welcome choice for Sharpes’s defence team. Avory, a notorious “hanging judge”, had been memorably described:

Manor Farm in Ladbroke dates back, according to the data on British Listed Buildings, to the mid 18th century. For architectural historians, it adds:

Manor Farm in Ladbroke dates back, according to the data on British Listed Buildings, to the mid 18th century. For architectural historians, it adds: