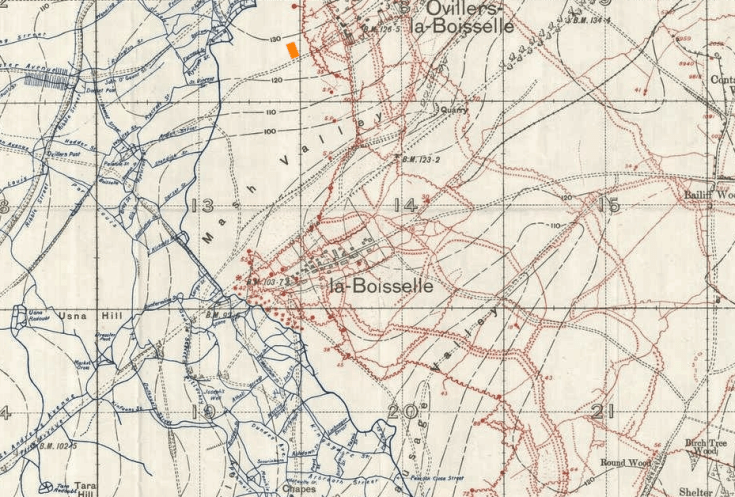

The guns that began their incessant thunder in August 1914 are, at last, silent. The German field army has surrendered, the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet lies at anchor in Scapa Flow, and Wilhelm himself has abdicated. In Paris, the great, the good – but more importantly, the victorious – are assembling to pick the bones out of five years of carnage. Meanwhile, we meet the Rutherford family. Their home is in Thurso, on the stormy north eastern coast of Scotland. Jack is just one of nearly 900,000 British men to have paid what was poetically called ‘the supreme sacrifice’. His sisters are both now in France: Corran is with a charity in Dieppe, bringing some sort of education to young soldiers who have had academic opportunities denied them for the last five years. Stella is in Paris, having been engaged as one of the hundreds of typists needed to record the decisions and arguments in the drama shortly to be played out at Versailles. Alex is still on Royal Navy duties, with his ship keeping a watchful eye on a war that is still being fought between Russian Bolsheviks and the Tsarists they overthrew.The novel follows the lives and loves of the Rutherford girls.

Flora Johnston handles the historical background well. It is now widely acknowledged that the Treaty of Versailles did not end the war between Germany and her enemies. It merely put it in on hold for twenty years. There was not to be a new world, or anything remotely like the ‘land fit for heroes’ that optimists imagined, either in Britain or France,and certainly not in Germany. In vain did US President Wilson strive for some kind of settlement that would be for all time. Who can blame France – with 1.4 million dead, thousands of villages reduced to rubble, its industry shattered and a priceless architectural heritage destroyed – for wanting to make Germany pay?

We see 1919 through many different eyes, and this is a story skillfully told. Arthur, Corran’s teacher colleague is embittered by the sacrifices his own parents made to educate him, and white-knuckled with anger that, back home, his own family, protesting against the lack of jobs, are faced with baton charges by police. Rob Campbell, once Corran’s intended fiancée, is worn down and traumatised by his work as a battlefield surgeon. His fondest hope is purely escapist, and it is that one day he might be able to relive his glory days on the rugby pitch. But with so many of his fellow players rotting under the French and Belgian soil, what hope does he have?

The game of rugby is a powerful motif in this story. in an England-Scotland game in March 1914 the thirty young men are at the peak of fitness, chests bursting with pride. Too many of those chests would, in the coming turmoil, simply become targets for German bullets and shell fragments. On New Year’s Day 1920, the first game of any consequence to follow the war was played, between France and Scotland. It is a small and hesitant step forward, but there are too many missing names of the teamsheets.

The story is a remarkable blend of history, romance and social observation. Flora Johnston is a fly on the wall at a bitter ceremony in a young man’s bedroom that must have been repeated countless times across Britain and, indeed, France, and Germany:

“She felt again the overwhelming sadness of sorting through Jack’s possessions yesterday. All over the country there were houses like this, filled with the ephemera of hundreds of thousands of lives that had unexpectedly ceased to exist. Clothes and footballs, bicycles and egg collections, razors and comics and diaries and gramophone records. So much of it: surely far too much for the nations attics or rubbish heaps or junk shops to absorb.”

The Peacemakers of Paris reaches out to so many different readers. WW1 buffs who appreciated Birdsong and Pat Barker’s trilogy will find something here. Those who like romance, a hint of heartbreak, but an optimistic ending will also be happy. Most importantly, anyone who enjoys a novel which is well researched with convincing characters will not be disappointed. Published by Allison & Busby, the book is available now.

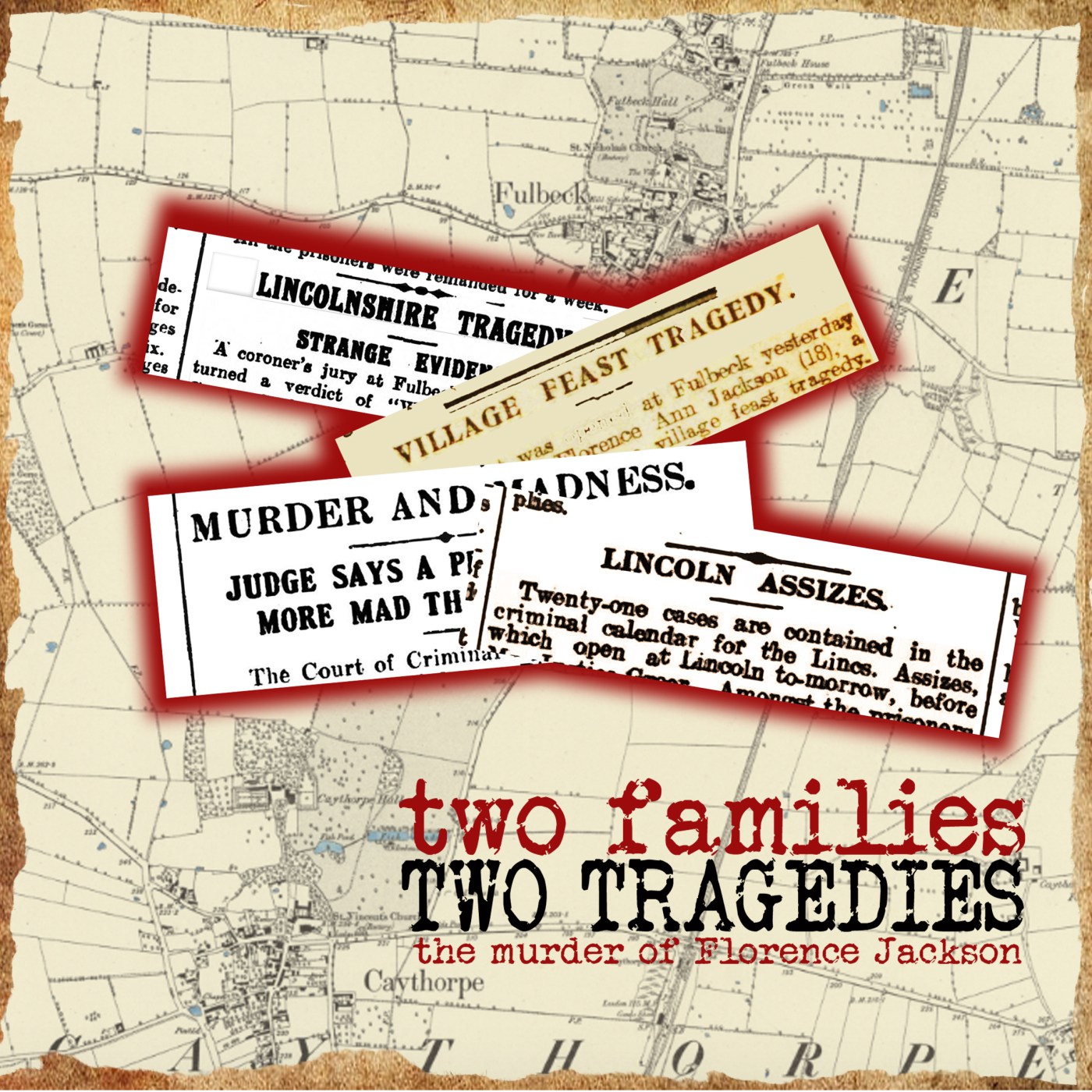

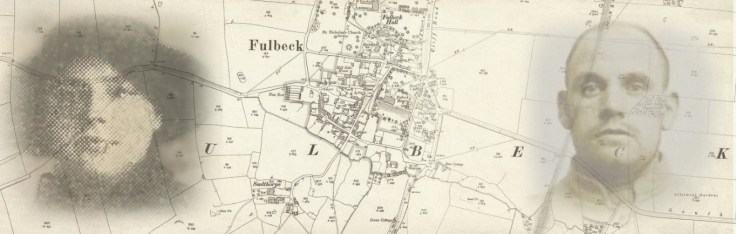

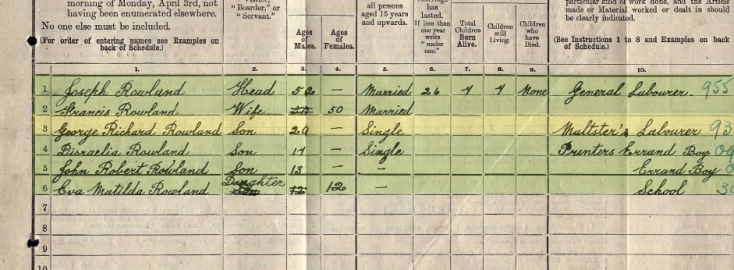

Now, though, we must return to Fulbeck. Only a grainy newspaper image of Florence Jackson remains, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to picture a pretty, round-faced girl with a confident gaze for the camera. Once again, the 1911 census is of service. She lived in Fulbeck with her family. Florence would not live to be noted in the 1921 survey. Opportunities for young women of humble birth in rural communities in those days were limited to farm work, or domestic service. There are suggestions that Florence has been in service at Barkston, or had returned to Fulstow in anticipation of a similar post. At some point she met Dick Rowland, and he was smitten, considering himself deeply in love. He was now 29, with a lifetime of horrors condensed into four years of hell on the Western Front, Florence was just 19, pretty, vibrant and untouched by the death and misery of The Great War.

Now, though, we must return to Fulbeck. Only a grainy newspaper image of Florence Jackson remains, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to picture a pretty, round-faced girl with a confident gaze for the camera. Once again, the 1911 census is of service. She lived in Fulbeck with her family. Florence would not live to be noted in the 1921 survey. Opportunities for young women of humble birth in rural communities in those days were limited to farm work, or domestic service. There are suggestions that Florence has been in service at Barkston, or had returned to Fulstow in anticipation of a similar post. At some point she met Dick Rowland, and he was smitten, considering himself deeply in love. He was now 29, with a lifetime of horrors condensed into four years of hell on the Western Front, Florence was just 19, pretty, vibrant and untouched by the death and misery of The Great War.