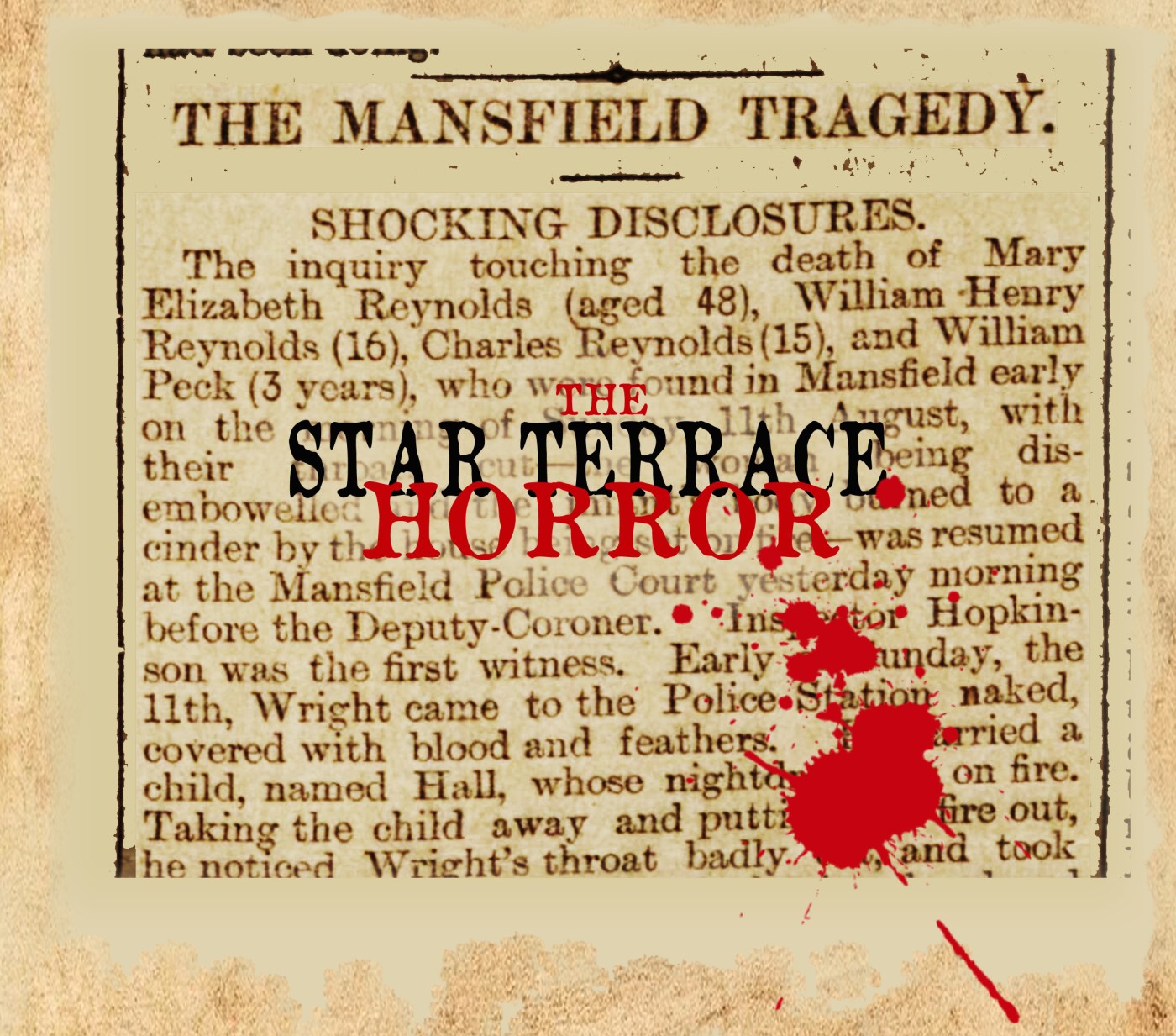

SO FAR: Mansfield, August 1895. Henry Wright, a foundry labourer, has been lodging at 1 Star Terrace, with Mary Elizabeth Reynolds and her step children. In the early hours of Sunday 11th August, Inspector Hopkinson, who lives at Commercial Street Police Station, is woken up by a commotion, and woken up outside his window. He finds Henry Wright, nearly naked, holding a small boy in a burning nightdress. Both Wright and the boy are covered in blood. Hopkinson leaves the pair with his wife and hurries to Wright’s lodging, just fifty yards down the street. The upstairs of the house is on fire, and George Reynolds is at his bedroom window shouting for help, but the fire brigade soon arrive, rescue George with a ladder, and then force an entry to the house.

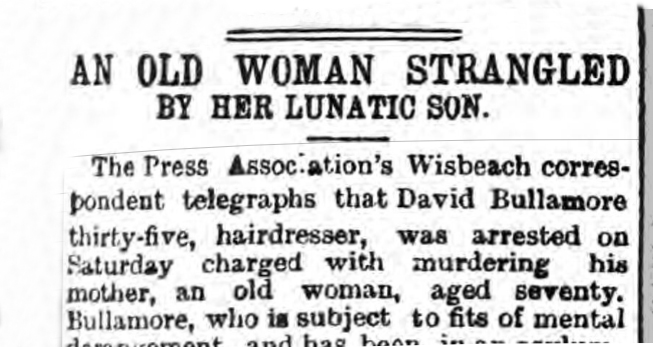

Downstairs is a scene from hell. Most subsequent newspaper reports rather glossed over the horror, merely saying that Mrs Reynolds was found dead, but one or two papers thought that their readers were made of sterner stuff.

Upstairs there was more horror. Charlie and William Reynolds were both dead, their throats cut and lying in pools of their own blood. In another bedroom was the charred remains of little William Peck, the grandchild.

Meanwhile, Inspector Hopkins’s wife had taken Wright and the child to the nearby workhouse. Wright’s wounds – to the neck, and self inflicted – were bandaged, and the Hall child had been taken to hospital. Wright, known as ‘Nenty’ had spoken to Mrs Hopkinson:

Hopkinson immediately charged Wright with the four murders (it could easily have been five, as he had secured George’s bedroom door tight shut with rope), and he was taken away to recover from his wounds, and await the magistrates’ court.

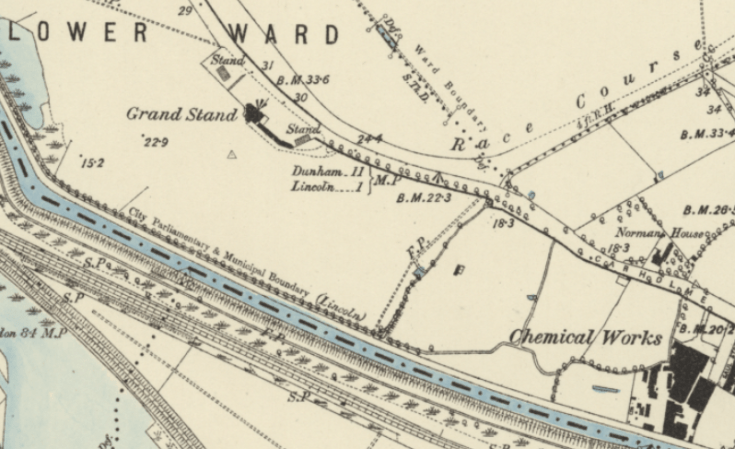

What do we know of Henry Wright? Very little, in truth. He was born in the town in 1862, and the family had lived for many years in the central thoroughfare of Leeming Street (above, in the early 1900s). They were still there in 1881, and Wright’s father, William was described as a nurseryman. His mother, Jane, had died the previous year. There is no record of him being involved in any kind of criminality, let alone terrifying violence. My first reaction to reading about the horrific mutilation of Mary Reynolds was to think of the scene of butchery that greeted those who discovered the remains of Mary Jane Kelly – Jack The Ripper’s last victim – in Millers Court Spitalfields, just seven years earlier. What possessed Wright – and I use that word advisedly – to commit his butchery of Mary Reynolds? We know that he had ‘romantic’ designs on the woman, and that he had been rejected, but this was not the work of an enraged and jealous spurned lover. This was the work of a madman.

As Wright lay under close guard at the workhouse, awaiting trial, there were bodies to be buried.

Inevitably, the Mansfield magistrates found Wright guilty of the four murders, and passed the case on to the Nottingham Assizes. There, in November, and equally inevitably, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. There seems to have been a fairly desultory attempt to suggest that he was insane, but medical reports suggested otherwise, and Mr Justice Day duly donned the Black Cap. The ritual appeal against the sentence was duly lodged, but the Home Secretary Matthew White Ridley (left), like the Nottingham jury and the judge before him, was having none of it, and the appeal was rejected. I am certain that the dire American import of ‘counting the sleeps until Christmas’ had not penetrated the British consciousness in December 1895, but I am sure youngsters across Nottinghamshire woke on the morning of Christmas Eve with a sense of anticipation.

In Bagthorpe Gaol, Nottingham (above) Henry Wright was experiencing an altogether different kind of anticipation.

There are more questions than answers with this case. I have been researching and writing about real-life historical murders for many years, and this is the worst murder I have ever encountered. The circumstances of most of the killings I have researched are similar and familiar. They include these elements:

Heat of the moment’ murders, unplanned but the result of rage.

Planned killings, usually involving stealth and often using poison.

Fatal violence as a result of ‘temporary insanity’, often fueled by drink.

Henry Wright mutilated Mary Reynolds’ body. He disemboweled her, cut off her breasts and destroyed her face with his razor, and then kept her gaping stomach parted open with a curtain rod, so that his work could be seen by those who discovered the carnage. All this was not done in an instant. It is not a ‘one punch’ death. It is not the fatal result of a skillfully placed knife thrust or a well aimed bullet.

There is something dark, disturbing and dreadful about the Star Terrace murders which will never be solved by writers like myself who rely on on old newspaper reports. Whatever the answer, it is buried in Henry Wright’s unmarked prison grave, dug as Christmas Eve 1895 gave way to the most joyful day in the Christian Calendar.

FOR MORE HISTORICAL MURDER CASES CLICK THIS LINK

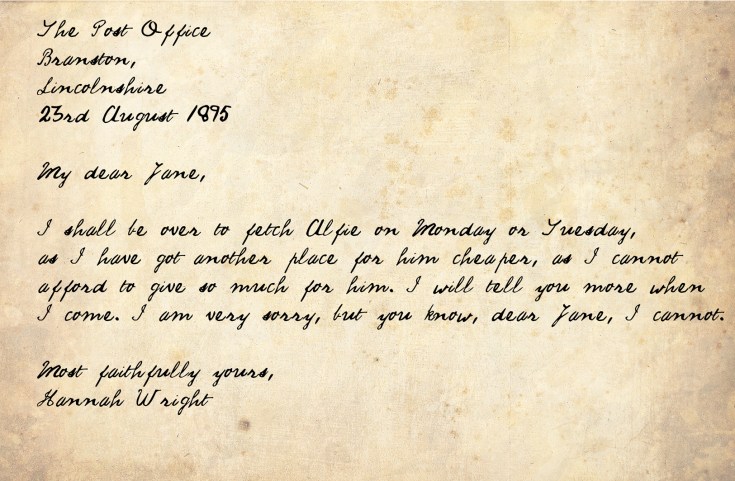

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.