England, 1899. We are in the city of Leeds and the hottest summer in living memory is taxing the patience of even the most placid citizens. The heavy industry which has transformed the quietly prosperous Yorkshire town continues to clatter and roar, while the smoke from its thousand chimneys coats everything in grime, and the air is thick with soot. Superintendent Tom Harper of the city’s police force has mixed feelings about his recent promotion. The pile of paperwork on his desk adds to the tedium, and he wishes he could be out there on the busy streets doing what he believes to be a copper’s real job.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Charlie Reed was a small time shop-keeper, but his shop was in an area where large scale commercial developments are being planned, and his premises – along with many others – have been targeted by thugs who are possibly in the pay of two wealthy – but utterly corrupt and ruthless – city councillors. Like a dog with a bone, Harper chews and gnaws away at the shrouds of secrecy with which these men have surrounded themselves, but Charlie Reed’s tragic suicide is eclipsed by a string of savage killings committed by a deranged pair of brothers who are clearly acting at the behest of the two councillors and their lawyer.

Against a background of heartbreaking poverty, where needless deaths and bureaucracy trump common humanity at every turn, Harper eventually gets to come face to face with the killers and their suave masters, but not before his family is put in peril, and his own life comes to hang from a thread.

The most chilling aspect of The Leaden Heart is that it is brutally contemporary. Town and City councillors might, these days, be seen as bumbling and pompous local jobsworths, full of piss and wind, but relatively harmless. Nothing could be further from the truth. Now, as in 1899, such people have huge power over planning applications and budgets which are in the millions. Now, as then, the corrupt and venal live among us and will, no doubt, be putting themselves up for re-election in May 2019.

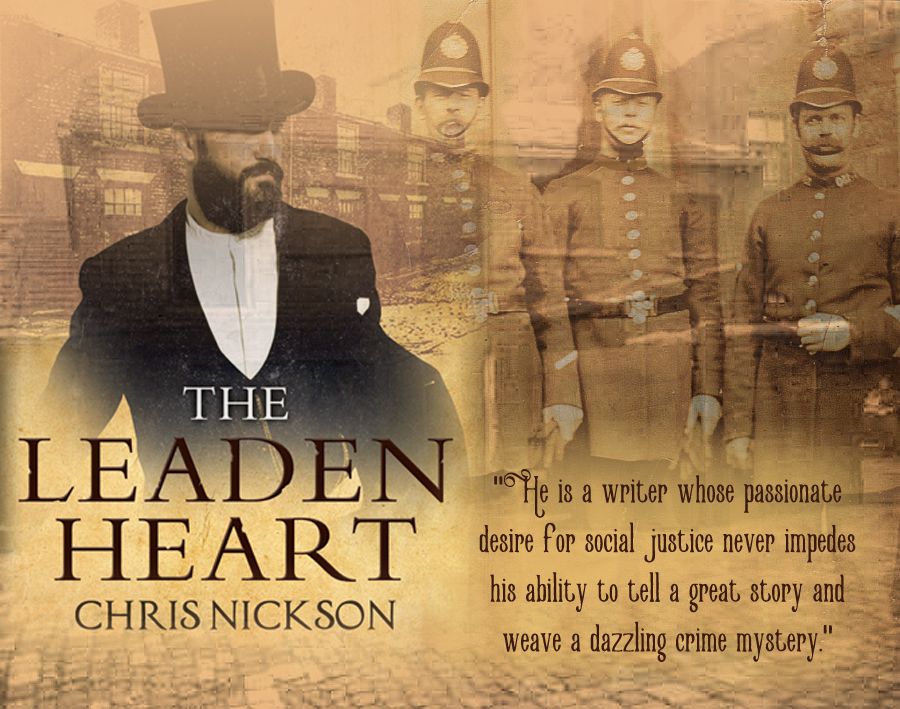

The author’s empathy with the downtrodden and exploited, and his disgust at crooked councillors and unfeeling public guardians burns like an angry flame. The most haunting image in the book is of two drowned children killed, yes, by their drunken father, but also failed by their helpless mother and the rigid workhouse system. Nickson is a writer, however, whose passionate desire for social justice never impedes his ability to tell a great story and weave a dazzling crime mystery. What is more, he does the job with minimal fuss; there’s never a wasted word, a redundant adjective or an overblown description. His prose is pared down to the bone, but always sharp and vivid. I often think Nickson would have found lasting kinship with the great campaigning journalist and author GR Simms, (incidentally an almost exact contemporary of Tom Harper) whose most celebrated work is echoed in some aspects of The Leaden Heart. The book is published by Severn House and will be out on 29th March.

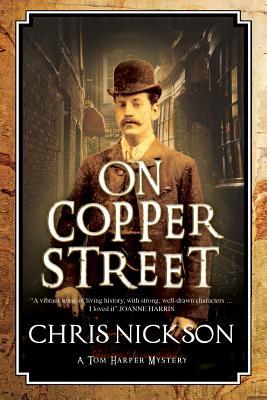

Regular visitors to Fully Booked will know that I am an unashamed fan of everything Chris Nickson writes. If you click on the image of the man himself, you can read other reviews and features on his work.

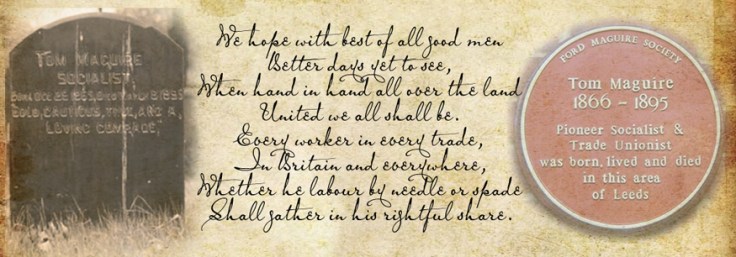

On Copper Street opens in grim fashion, with death and disfigurement. The dead pass in contrasting fashion. Socialist activist Tom Maguire dies in private misery, stricken by pneumonia and unattended by any of the working people whose status and condition he championed. The death of petty crook Henry White is more sudden, extremely violent, but equally final. Having only just been released from the forbidding depths of Armley Gaol, he is found on his bed with a fatal stab wound. If all this isn’t bad enough, two children working in a city bakery have been attacked by a man who threw acid in their faces. The girl will be marked for life, but at least she still has her sight. The last thing the poor lad saw – or ever will see – is the momentary horror of a man throwing acid at him. His sight is irreparably damaged.

On Copper Street opens in grim fashion, with death and disfigurement. The dead pass in contrasting fashion. Socialist activist Tom Maguire dies in private misery, stricken by pneumonia and unattended by any of the working people whose status and condition he championed. The death of petty crook Henry White is more sudden, extremely violent, but equally final. Having only just been released from the forbidding depths of Armley Gaol, he is found on his bed with a fatal stab wound. If all this isn’t bad enough, two children working in a city bakery have been attacked by a man who threw acid in their faces. The girl will be marked for life, but at least she still has her sight. The last thing the poor lad saw – or ever will see – is the momentary horror of a man throwing acid at him. His sight is irreparably damaged. Nickson is a master story teller. There are no pretensions, no gloomy psychological subtext, no frills, bows, fancies or furbelows. We are not required to wrestle with moral ambiguities, nor are we presented with any philosophical conundrums. This is not to say that the book doesn’t have an edge. I would imagine that Nickson (right) is a good old-fashioned socialist, and he pulls no punches when he describes the appalling way in which workers are treated in late Victorian England, and he makes it abundantly clear what he thinks of the chasm between the haves and the have nots. Don’t be put off by this. Nickson doesn’t preach and neither does he bang the table and browbeat. He recognises that the Leeds of 1895 is what it is – loud, smelly, bustling, full of stark contrasts, yet vibrant and fascinating. Follow this link to read our review of the previous Tom Harper novel,

Nickson is a master story teller. There are no pretensions, no gloomy psychological subtext, no frills, bows, fancies or furbelows. We are not required to wrestle with moral ambiguities, nor are we presented with any philosophical conundrums. This is not to say that the book doesn’t have an edge. I would imagine that Nickson (right) is a good old-fashioned socialist, and he pulls no punches when he describes the appalling way in which workers are treated in late Victorian England, and he makes it abundantly clear what he thinks of the chasm between the haves and the have nots. Don’t be put off by this. Nickson doesn’t preach and neither does he bang the table and browbeat. He recognises that the Leeds of 1895 is what it is – loud, smelly, bustling, full of stark contrasts, yet vibrant and fascinating. Follow this link to read our review of the previous Tom Harper novel,