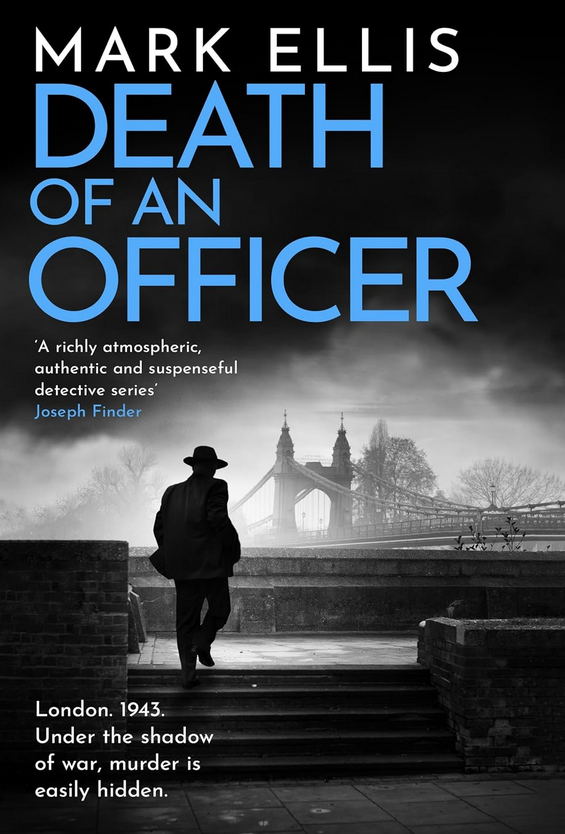

Detective Chief Inspector Frank (christened Francisco) Merlin is a thoroughly likeable and convincing central character in this murder mystery, set in 1943 London. As in all good police novels, there is more than one murder. The first we are privy to is that of a seemingly inoffensive consultant surgeon, Mr Dev Sinha, found dead in his bedroom, apparently bludgeoned with a hefty statue of Ganesha, the Hindu elephant god. Sinha’s wife has been diagnosed with a serious mental illness, and has been packed off to an institution near Coventry ( no jokes please) but when she is interviewed she is more lucid than those around her have been led to believe.

Added to Merlin’s list of corpses is that of south London scrap dealer called Reg Mayhew, apparently victim of the delayed detonation of a German bomb. Unfortunately for the investigators, the word ‘corpse’, suggesting an intact body, is misleading. Mayhew’s proximity to the blast has given the lie to the old adage about someone’s inability to be in two places at once.

Clumsily concealed beneath bomb site rubble in the East End is the well-dressed (evening attire and dress shirt) remains of Andrew Corrigan, a Major in the US army. It seems he was a ‘friend’ of a rich and influential MP, Malcolm Trenton.

Merlin’s investigations take him towards the contentious issue of Indian independence, and it seems that the murdered consultant was a member of a committee comprising prominent British Indians who support Subhas Chandra Bose, a firebrand nationalist who is seeking support from Nazi Germany and Japan, in the belief that they would win the war, and then look favourably on an independent India.

Like all good historical novelists, Mark Ellis has done his homework to make sure we feel we are in the London of spring 1943. We are aware of the recent Bethnal Green Tube disaster, that Mr Attlee is a key member of Churchill’s coalition government, and that a Dulwich College alumni has just had his latest novel, The Lady in the Lake, published. We also know that the Americans are in town. As Caruso sang in 1917, the boys are definitely ‘Over There!‘Among the 1943 intake is Bernie Goldberg, a grizzled American cop, now attached to Eisenhower’s London staff.

I am old, but not so ancient that I can remember WW2 London. Many fine writers, including Evelyn Waugh in his Sword of Honour trilogy, and John Lawton with his Fred Troy novels, have set the scene and established the atmosphere of those times, and Mark Ellis treads in very worthy footsteps. There is the dismal food, the ever present danger of air raids, the sheer density of the evening darkness and the constant reminder of sons, brothers and husbands risking their lives hundreds of miles away. Ellis also reminds us that for most decent people, the war was a time to pull together, tighten the belt, shrug the shoulders and get on with things. Others, the petty and not so petty criminals, saw the chance to exploit the situation, and get rich quickly.

Central to the plot is ‘the love that dare not speak its name‘ in the shape of an exclusive club organised by Maltese gangsters. Mark Ellis reminds us that there were no rainbow pedestrian crossings or Pride flags flying over public buildings in 1943, and that there was an ever-present danger that men in public life were susceptible to blackmail on account of their sexual preferences. With a mixture of good detective work and a bit of Lady Luck, Merlin and his team solve the murders. The book’s title is ambiguous, in that Major Andrew Corrigan certainly fits the bill, but there is one other officer casualty – I will leave you to find out for yourself his identity by reading this impeccably atmospheric and thoroughly entertaining period police thriller. It will be published by Headline Accent on 29th May.