Hannah Elizabeth Wright was born on 25 August 1872 to John Wright, an agricultural labourer, and Mary Anne Key in Kirkby la Thorpe, a tiny village a few miles east of Sleaford. The 1881 census recorded 256 souls.

Hannah was the youngest of five children, two boys and three girls. Sadly, her mother died when she was four. Her father remarried so she was brought up by her stepmother. There were few options for young women ‘of humble birth’ in rural communities in those days. It was either work on the land, or go into service – meaning a live-in position with some wealthy family, either as a cook or a general maid. The census in 1891 shows us that Hannah was working in The Manor House at Ewerby, less than two miles from Kirkby. Her employer was Mr William Andrews, a farmer. The Manor House (left) still stands.

By 1893, she had moved further away to the village of Weston, near Newark. It was here that she began a relationship with a local lad and became pregnant. Alfred Edward Wright was born on 3rd November 1893. He was, by all accounts, a healthy child, but his father quickly disappeared from the scene, and became engaged to another woman. This left Hannah in a dire situation. With no other means of support other than her own work, how was she going to bring up Alfie? A solution – of a kind – was found when a Weston woman called Jane Flear offered to take the boy in – for a price.

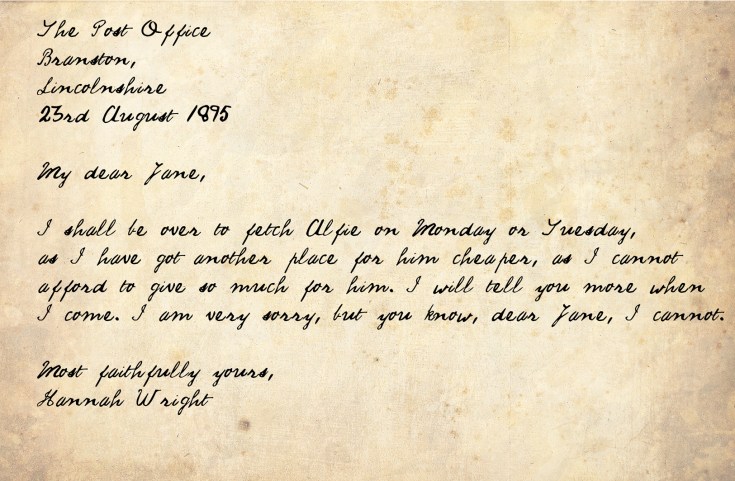

We know that by 1895 Hannah was working for a family in Branston, south of Lincoln, and had begun another relationship, with a young man called William Spurr, but she kept Alfie’s existence from him. Hannah had already fallen into arrears with her payments for Alfie, but her problems became worse when she received word from Miss Flear that the price for looking after the little boy was to be raised to three shillings and sixpence each week. Using the Bank of England inflation calculator, that would be nearly £38 In modern money, probably more than Hannah earned each week, given that her food and housing would come with the job.

Jane Flear received this letter (facsimile) from Hannah:

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Hannah Wright arrived in Weston on the afternoon of Monday 26th August to collect Alfie. Miss Flear had misgivings about handing over the little boy, and thought that Hannah was in something of a disturbed state. When she went to collect the rest of Alfie’s clothes, Hannah said she didn’t want to take them. The three of them, Jane Flear wheeling Alfie in his pram, set off to walk the two miles to Crow Park station, just outside Sutton on Trent. Hannah and Alfie caught the 6.15 train to Retford. Jane Flear never saw Alfie alive again. Hannah eventually returned to the little terraced house in Alexandra Terrace late on the Monday evening,and explained to Jane and William Wright that her little boy was still in Weston, but she had arranged for someone to adopt him permanently. Jane Wright asked her sister in law if she had discussed the situation with William Spurr, but despite Jane telling her that it was wrong to keep back something so important, Hannah was adamant that he was not to be told. They all retired to bed at 11.30 pm. The next morning, at about 9.30 am, Hannah announced that she was going to visit some friends, and would return later.

IN PART TWO

A CONFESSION

A TRIAL

THE BLACK CAP

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

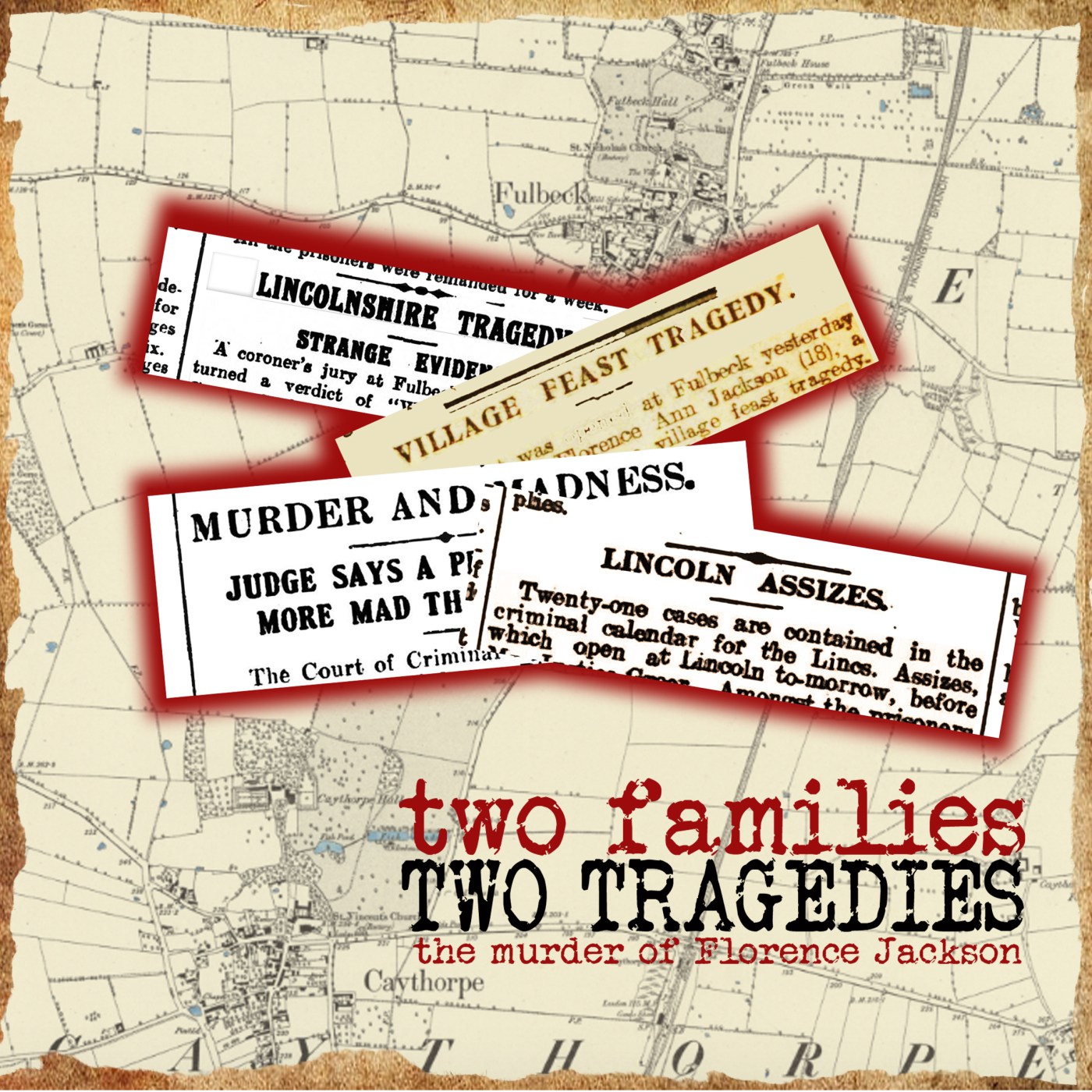

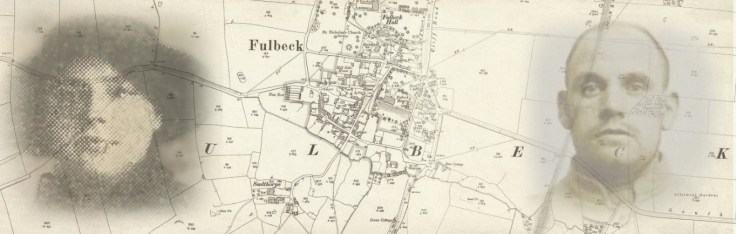

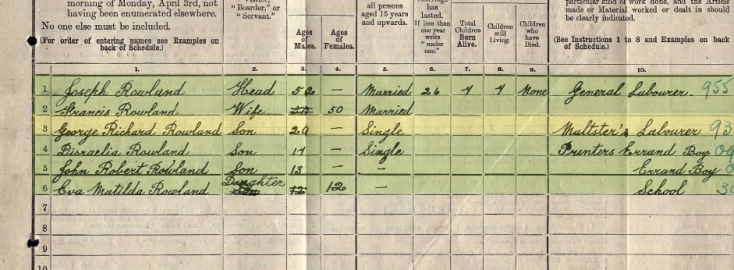

Now, though, we must return to Fulbeck. Only a grainy newspaper image of Florence Jackson remains, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to picture a pretty, round-faced girl with a confident gaze for the camera. Once again, the 1911 census is of service. She lived in Fulbeck with her family. Florence would not live to be noted in the 1921 survey. Opportunities for young women of humble birth in rural communities in those days were limited to farm work, or domestic service. There are suggestions that Florence has been in service at Barkston, or had returned to Fulstow in anticipation of a similar post. At some point she met Dick Rowland, and he was smitten, considering himself deeply in love. He was now 29, with a lifetime of horrors condensed into four years of hell on the Western Front, Florence was just 19, pretty, vibrant and untouched by the death and misery of The Great War.

Now, though, we must return to Fulbeck. Only a grainy newspaper image of Florence Jackson remains, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to picture a pretty, round-faced girl with a confident gaze for the camera. Once again, the 1911 census is of service. She lived in Fulbeck with her family. Florence would not live to be noted in the 1921 survey. Opportunities for young women of humble birth in rural communities in those days were limited to farm work, or domestic service. There are suggestions that Florence has been in service at Barkston, or had returned to Fulstow in anticipation of a similar post. At some point she met Dick Rowland, and he was smitten, considering himself deeply in love. He was now 29, with a lifetime of horrors condensed into four years of hell on the Western Front, Florence was just 19, pretty, vibrant and untouched by the death and misery of The Great War.

I must confess to not having read anything by Robert Goddard (left) for a few years. Back in the day I enjoyed his James Maxted trilogy, which comprised The Ways of the World (2013), The Corners of the Globe (2014) and The Ends of The Earth (2015), which focused on a young former RAF pilot and his involvement in the political fallout in Europe after the Versailles Conference ended in 1920. I reviewed his standalone novel

I must confess to not having read anything by Robert Goddard (left) for a few years. Back in the day I enjoyed his James Maxted trilogy, which comprised The Ways of the World (2013), The Corners of the Globe (2014) and The Ends of The Earth (2015), which focused on a young former RAF pilot and his involvement in the political fallout in Europe after the Versailles Conference ended in 1920. I reviewed his standalone novel