Rosa Armstrong was born in 1915, the daughter of Frederick Armstrong and his wife Maria. Her father died just three years later, but her mother remarried – to Edward Buttery – in 1920. June 1924 saw them living at 78 Alfreton Road, Sutton in Ashfield. Nine year-old Rosa attended the Huthwaite Road Council School, just ten minutes’ walk away along Douglas Road. Rosa’s older sister, Ethel (31), had not been lucky in her marriages. She had married William Parnham in August 1912, but on 18th June 1916, he died of wounds in France. Ethel married again, to Edward Mordan, a year later. An Edward Mordan is recorded as being killed in September 1918. At some point after the war, Ethel married again, to Arthur Simms, a miner, and in 1924 they were living in Phoenix Street, Sutton in Ashfield.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that Arthur Simms was reported as having served in the army – in both India and France – during the Great War, and that he had been taken prisoner by the Germans. He was born in 1899, so – unless he had lied about his age – the earliest he could have entered the war was 1917. Keep this in the back of your mind, because I will return to it later.

I am fairly ancient, and when I was at school, lunchtimes were long enough to allow children to go home for lunch. In the 1950s and 1960s, with just a few exceptions, I always walked or cycled home for lunch. Rosa Armstrong’s journey was less than a mile, and on Friday 27th June, she came home for lunch as usual, and as she prepared to go back to school, she asked her mother for sixpence to pay for her school photograph. Her mother, Maria, said that she would come to the school herself and pay for the photograph. Rosa never made it back to school for the afternoon’s lessons.

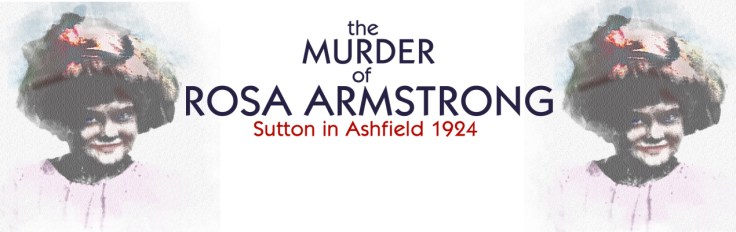

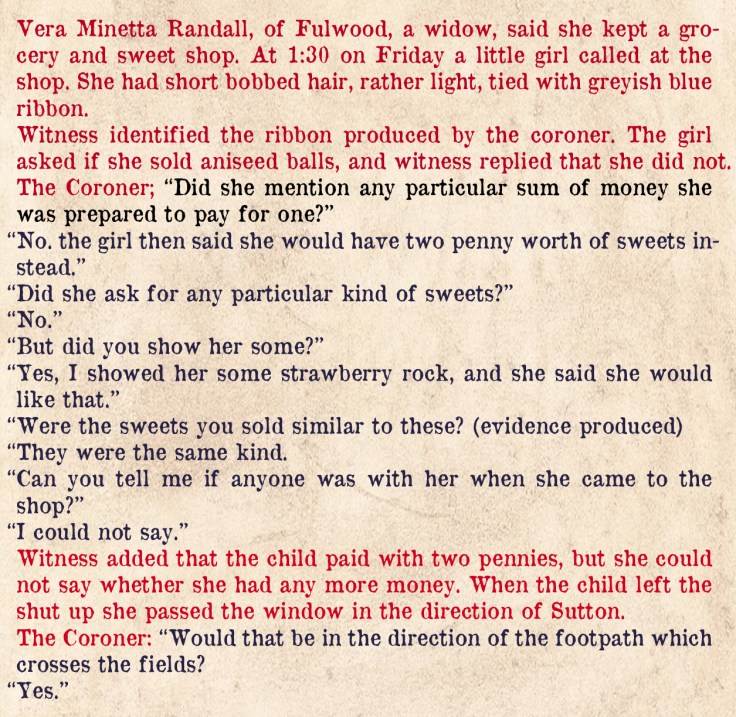

Fulwood no longer exists as a separate place, but back in the day it had its own identity as a small community south-west of Sutton and south of what is now the A38. In 1924, there was a sweet shop. Its owner was later to testify.

When Rosa didn’t return home at the end of the afternoon, her mother was horrified to learn that Rosa hadn’t said “Yes, Sir” at afternoon registration. Deeply worried, she tried asking everywhere, even making it to the home of her daughter Ethel, but she drew blanks everywhere.

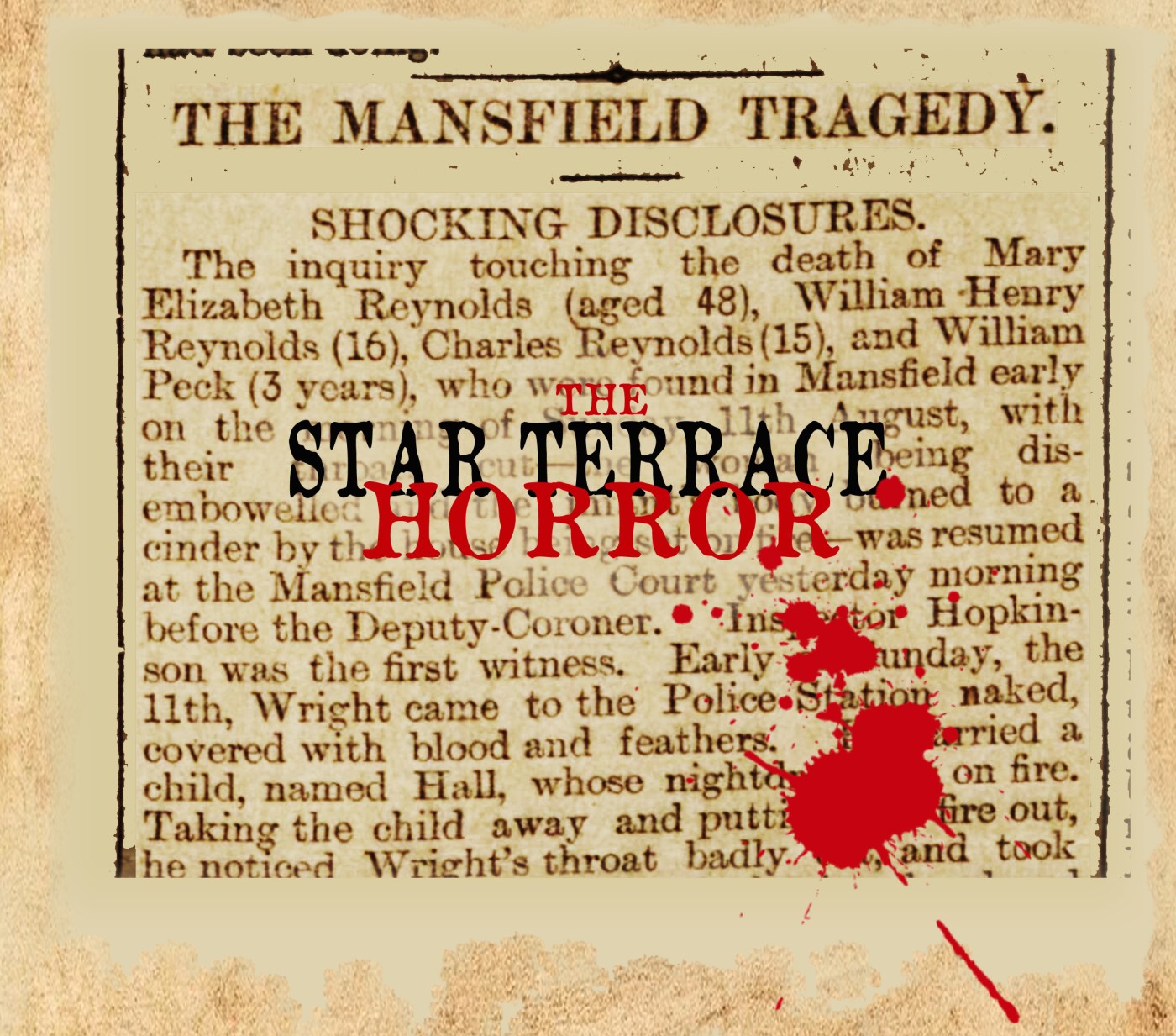

Police Constable Cheeseman was bored, tired and foot-sore, as he did his nocturnal rounds in Mansfield, four miles or so up the road from Rosa’s home. At 2.00 am, the early hours of 29th June, he was leaning against a wall in the Market Place, thinking about bed, supper, and sleep, when he was startled to see a young man, apparently sober, making his way towards him. The newspapers later carried this report:

PC Cheeseman recounted the story of how Simms gave himself up to him in Mansfield Market Place in the early hours of the morning. As he was standing at the bottom of Stockwell Gate, he said he saw the prisoner approaching from the direction of Sutton The man came up to him and said,

“Policeman, I want to give myself up.” He asked what for and Simms replied,

“For murder. It’s my wife’s little sister at Sutton. I have done it at Sutton this afternoon.”

The constable took him to the police station and there said,

“Do you realise the seriousness of your statement?” Simms replied,

“Yes, I do.”

“When I next cautioned him that anything he said would be used as evidence against him,” continued PC Cheeseman. Simms said,

“You will find her under the hedge in the second field of mowing grass near Saint Marks Church Fulwood. I strangled her with my hands. I will put it on paper if you like.”

IN PART TWO

A HORRIFYING DISCOVERY

A FUNERAL

RETRIBUTION

AN UNSOLVED MYSTERY

The Big Sleep was published in 1939, but the iconic film version, directed by Howard Hawks, wasn’t released until 1946. Are the dates significant? There is an obvious conclusion, in terms of what took place in between, but I am not sure if it is the correct one. The novel introduced Philip Marlowe to the reading public and, my goodness, what an introduction. The second chapter, where Los Angeles PI Marlowe goes to meet the ailing General Sternwood who is worried about his errant daughters, contains astonishing prose. Sternwood sits, wheelchair-bound, in what we Brits call a greenhouse. Marlowe sweats as Sternwood tells him:

The Big Sleep was published in 1939, but the iconic film version, directed by Howard Hawks, wasn’t released until 1946. Are the dates significant? There is an obvious conclusion, in terms of what took place in between, but I am not sure if it is the correct one. The novel introduced Philip Marlowe to the reading public and, my goodness, what an introduction. The second chapter, where Los Angeles PI Marlowe goes to meet the ailing General Sternwood who is worried about his errant daughters, contains astonishing prose. Sternwood sits, wheelchair-bound, in what we Brits call a greenhouse. Marlowe sweats as Sternwood tells him:

The book began with an optimistic Marlowe:

The book began with an optimistic Marlowe:

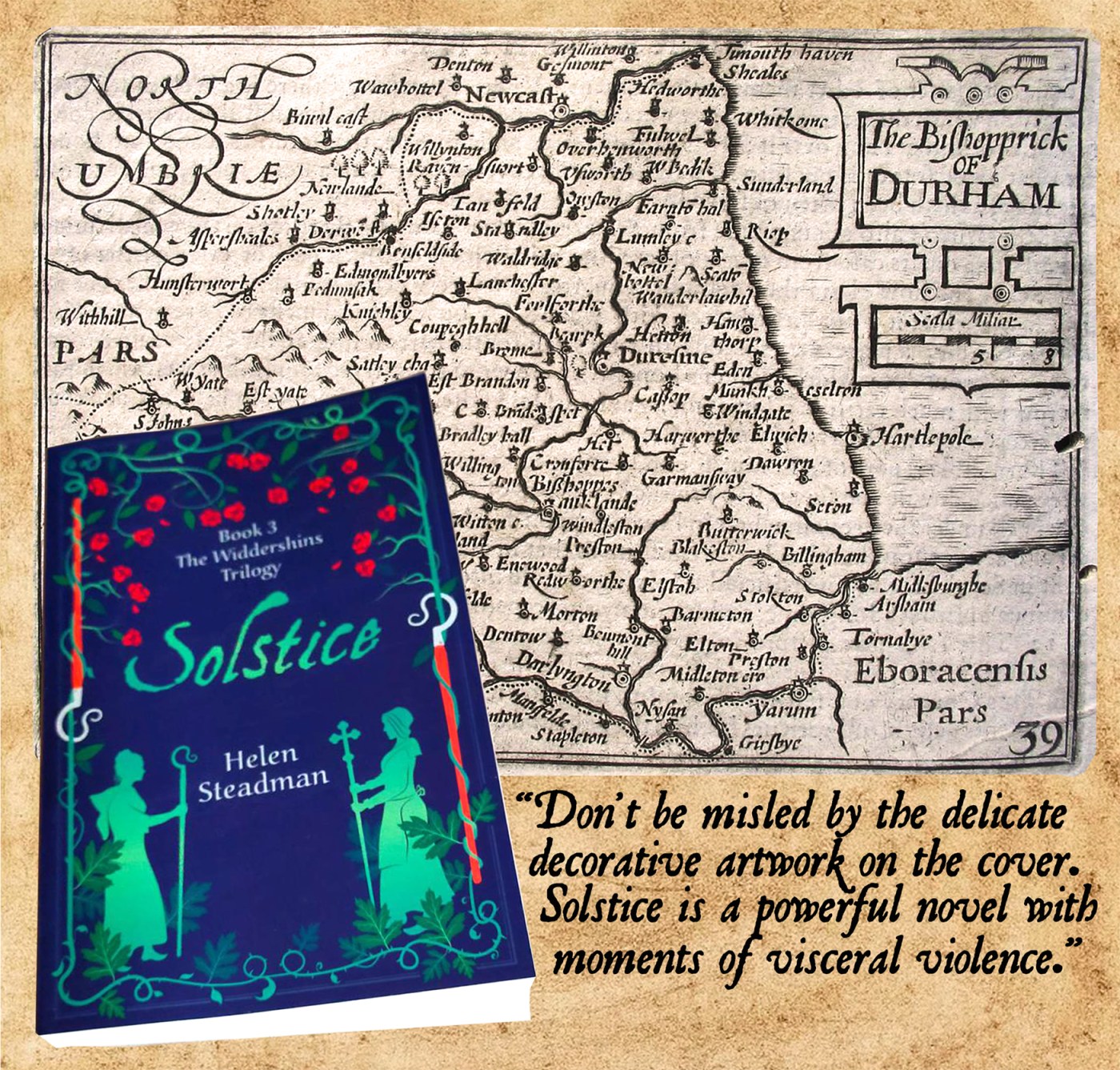

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it. Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus: