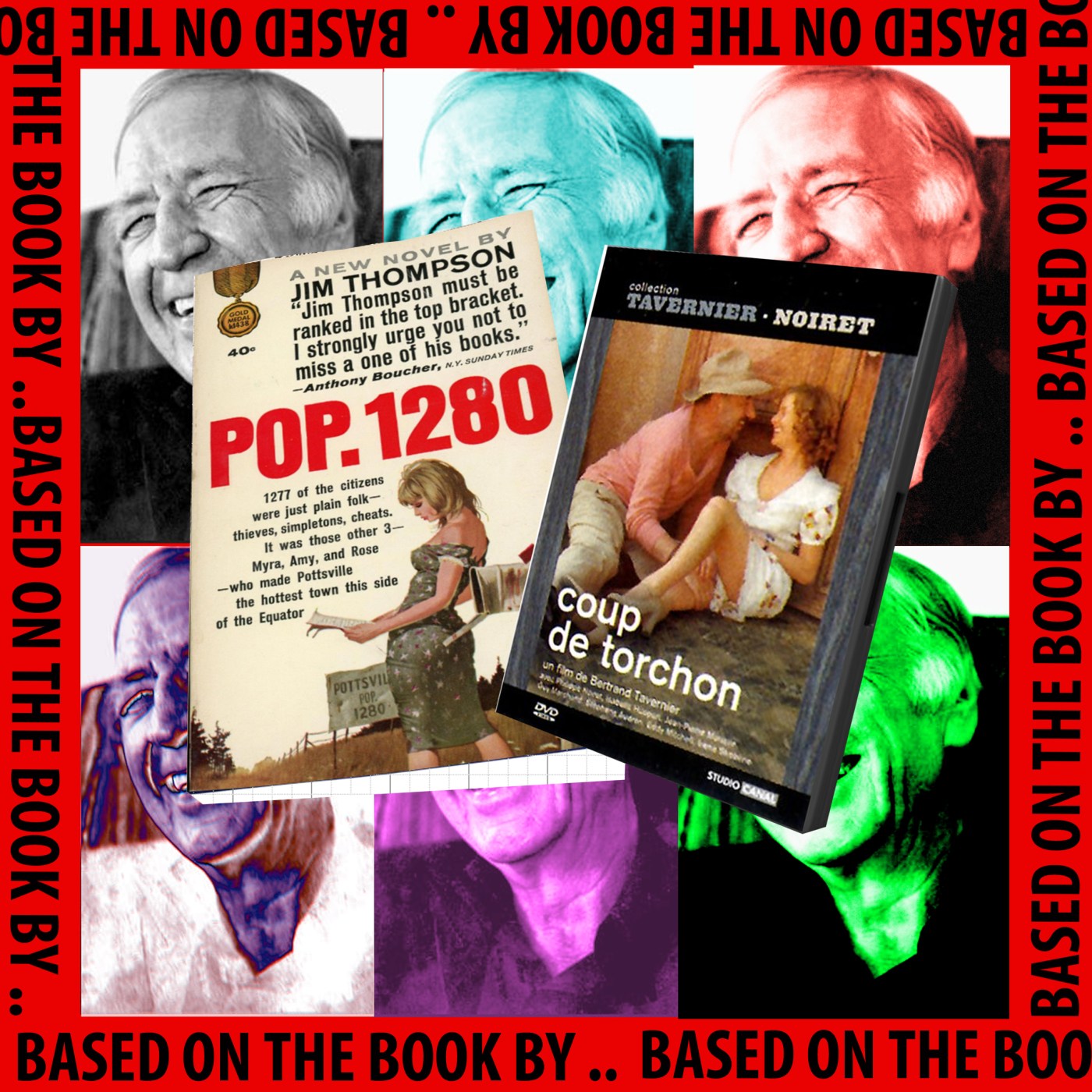

Jim Thompson loved the theme of a corrupt small town lawman, as in The Killer Inside Me, but what makes Pop. 1280 different is that Nick Corey, Sheriff of Pottsville, basks in his reputation as a bumbling buffoon, whereas Lou Ford’s outward persona was that of someone who was fairly shrewd, but otherwise unremarkable. Both novels employ the first-person narrative. The Killer Inside Me was published in 1952 (click this link for a feature on the novel and its film adaptations) but Pop. 1280 came out in 1962. To date, it has only been filmed once, as Coup de Torchon (Clean Slate) in 1981. The French film was directed by Bertrand Tavernier and starred Philippe Noiret as the central character.

To judge from the lurid cover illustrations of the novel you would be forgiven for supposing that it was set in the 1950s, but it actually takes place around the time of World War One, probably before America entered the war, as we hear Corey ask a man reading a newspaper

“What do you think about them Bullshevicks? Do you reckon they’ll ever overthrow the Czar?”

Coup de Torchon, strangely, is set in French Colonial Africa just before the outbreak of World War Two. This trailer gives some indication of the ambience:

The novel is an astonishing blend of slapstick comedy, bizarre sex (Cory’s wife is in a relationship with her retarded brother) and disturbing violence. On of the comedy scenes makes it almost untouched into the film. Cory is bothered by an insanitary privy that sits just outside the courthouse where he lives. Unable to convince the town worthies to have it removed, he takes advice from a neighboring Sheriff, a couple of train stops down the line. Remember this the deep South, probably Texas, and automobiles are rare (although Thompson does give some of the characters telephones):

“I sneaked out to the privy late that night, and I loosened a nail here and there, and I shifted the floor boards around a bit.”

Next day, one of the town’s leading citizens heads to the privy, his breakfast having provoked an urgent response:

“He went rushing in that morning, the morning after I’d done my tampering – a big fat fella in a high white collar and a spanking new broadcloth suit. The floor boards went out from under him, and down into the pit. And he went down with them. Smack down into thirty years’ accumulation of night soil.”

Readers of my generation idolised Joseph Heller’s magisterial one-off, Catch 22, and I vividly remember a dramatic mood shift towards the end of the book. The clowning and absurdities are paused for a spell, and a cold wind – both literal and metaphorical – blows through the streets of the Italian town where Yossarian and his buddies seek their entertainment. The genial but seemingly harmless Captain ‘Aarfy’ Aadvark has just murdered an Italian prostitute, and thinks no more of it than if he had crushed a bug under his boot. I remember being shocked back then and, similarly, Jim Thompson, via Nick Corey, lets rip about the realities of hard scrabble small town America:

“There were the helpless little girls, crying when the own daddies crawled into bed with ’em. There were the men beating their wives, the women screaming for mercy. There were the kids wettin’ in the beds from fear and nervousness and their mothers dosing them with red pepper for punishment. There were the haggard faces, drained white from hookworm and blotched with scurvy. There was the near starvation, the never-bein’-full, the debts-that-always-outrun-the-credit. There was that how-we-gonna-eat, how-we-gonna sleep, how-we-gonna-cover-our-poor-bare-asses thinking.”

Nick Corey sets about framing first one person and then another for various crimes, executes four more with his own hand, mainly to keep his job, and his triple relationships with various women, namely his wife Myra, Rose Hauck and the rather aristocratic Amy Mason. He delivers a running commentary on all these manoeuvers, always in the same Good Ol’ Boy “Aaw shucks, God dang it honey!” homely vernacular, which only makes starker the contrast between the man he wants to appear to be and the man he actually is. Thompson also has a sly chuckle at the expense of the heritage of the American South by naming tow of Pottsville’s dignitaries Robert Lee Jefferson and Stonewall jackson Smith.

My French is nowhere near good enough to know how closely the film script kept to Thompson’s original, or even if there is a similar trope in French culture to that of the tumbleweed town in the American South, but Coup de Torchon retains the main characters and plot direction. The equivalent characters and actors are:

Nick Corey Lucien Cordier Phillipe Noiret

Myra Corey Huguette Stéphane Audran

Lennie Nono Eddy Mitchell

Rose Hauck Rose Marcaillou Isabelle Huppert

Amy Mason Anne Irène Skoblene

Ken Lacey Marcel Chavasson Guy Marchand

There are some books that cannot be filmed. It’s as simple as that. Mike Nichols made a brave stab at Catch 22 (1970) and, despite hiring a stellar cast, never quite recaptured the moral anarchy of the novel. Quite wisely, producers and directors have never attempted adaptations of any Derek Raymond novels. How would you even start to put I Was Dora Suarez on screen? It has to be said that Corp de Torchon was a brave attempt to capture the essence of Thompson’s caustic and abrasive novel, but since what happens in Pottsville is nothing short of a dive into the middle of a townscape imagined by Hieronymus Bosch, Bertrand Tavernier and his crew have to given full marks for trying.

If the tags “Oxford”, “Murder” and “Detective” have you salivating about the prospect of real ale in ancient pubs, choirs rehearsing madrigals in college chapels, and the sleuth nursing a glass of single malt while he listens to Mozart on his stereo system, then you should look away now. Simon Mason (left) brings us an Oxford that is very real, and very now. The homeless shiver on their cardboard sleeping mats in deserted graveyards, and the most startling contrast is the sight of Range Rovers and high-end Volvos cruising into car washes manned by numerous illegal immigrants from God-knows-where, all controlled by criminals, probably embedded within the Albanian mafia.

If the tags “Oxford”, “Murder” and “Detective” have you salivating about the prospect of real ale in ancient pubs, choirs rehearsing madrigals in college chapels, and the sleuth nursing a glass of single malt while he listens to Mozart on his stereo system, then you should look away now. Simon Mason (left) brings us an Oxford that is very real, and very now. The homeless shiver on their cardboard sleeping mats in deserted graveyards, and the most startling contrast is the sight of Range Rovers and high-end Volvos cruising into car washes manned by numerous illegal immigrants from God-knows-where, all controlled by criminals, probably embedded within the Albanian mafia.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

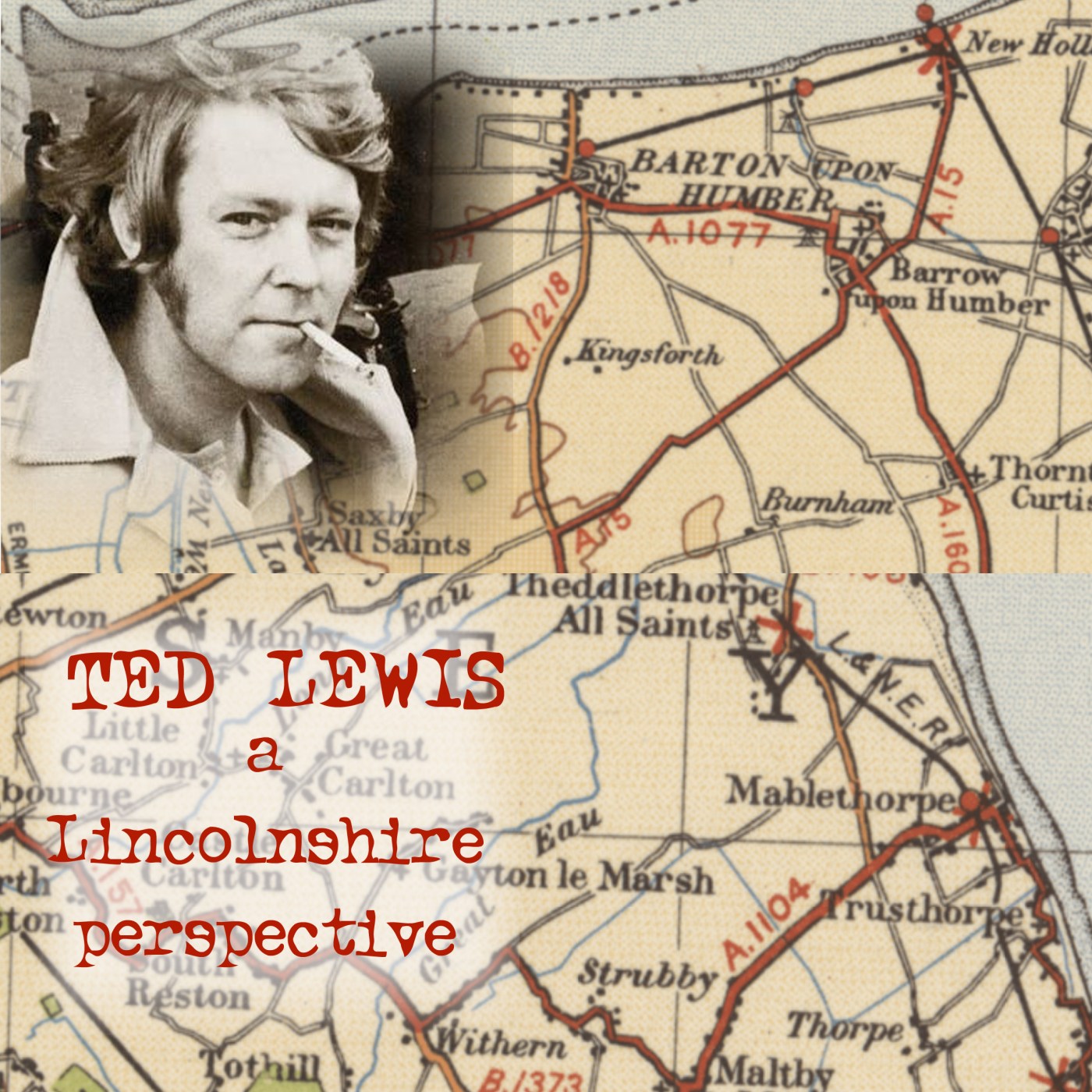

Alfred Edward Lewis was born in Stretford, Manchester on 15th January 1940, but in 1946 the family moved to Barton upon Humber. Five years later, Lewis passed his 11+ and began attending the town’s grammar school. There, he was fortunate enough to come under the influence of an English teacher called Henry Treece. Treece was born in Staffordshire, but had moved to Lincolnshire in 1939, and although he ‘did his bit’ as an RAF intelligence officer, he was able to make his name during the war years as a poet.

Alfred Edward Lewis was born in Stretford, Manchester on 15th January 1940, but in 1946 the family moved to Barton upon Humber. Five years later, Lewis passed his 11+ and began attending the town’s grammar school. There, he was fortunate enough to come under the influence of an English teacher called Henry Treece. Treece was born in Staffordshire, but had moved to Lincolnshire in 1939, and although he ‘did his bit’ as an RAF intelligence officer, he was able to make his name during the war years as a poet. After leaving the college, it seemed that Lewis was going to make his way as an artist and illustrator, and a book written by Alan Delgado, variously called The Hot Water Bottle Mystery or The Very Hot Water Bottle, can be had these days for not very much money, and the description on seller sites usually adds “Illustrated by Edward Lewis”. That was the first serious money Ted ever made. He moved to London in the early 1960s to further his prospects.

After leaving the college, it seemed that Lewis was going to make his way as an artist and illustrator, and a book written by Alan Delgado, variously called The Hot Water Bottle Mystery or The Very Hot Water Bottle, can be had these days for not very much money, and the description on seller sites usually adds “Illustrated by Edward Lewis”. That was the first serious money Ted ever made. He moved to London in the early 1960s to further his prospects. His first published novel was All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965) and it is a semi-autobiographical account of the lives and loves of art students in Hull. I remember borrowing it from the local library not long after it came out and, looking back, it was a far cry from the novels that would make Lewis’s fame and fortune.

His first published novel was All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965) and it is a semi-autobiographical account of the lives and loves of art students in Hull. I remember borrowing it from the local library not long after it came out and, looking back, it was a far cry from the novels that would make Lewis’s fame and fortune.  of the finest British films ever made. It was released in March 1970, and Lewis is credited, along with director Mike Hodges, with the screenplay. Incidentally, a hardback first edition of JRH can be yours – a snip at just £3,250 (admittedly with a hand-written note by the author)

of the finest British films ever made. It was released in March 1970, and Lewis is credited, along with director Mike Hodges, with the screenplay. Incidentally, a hardback first edition of JRH can be yours – a snip at just £3,250 (admittedly with a hand-written note by the author) believe to be his finest was GBH, published in 1980. Here, he unequivocally returns to Lincolnshire, and a bleak and down-beat out-of-season seaside town which is obviously Mablethorpe. The central character is George Fowler, a mobster who has made a living out of distributing porn movies, but has crossed the wrong people, and needs somewhere to hide up for a while. Rather like his creator, Fowler is in the darkest of dark places, and the novel ends in brutal and surreal fashion on a deserted Lincolnshire beach, with the wind howling in from the north sea as Fowler meets his maker in the remains of an RAF bombing target.

believe to be his finest was GBH, published in 1980. Here, he unequivocally returns to Lincolnshire, and a bleak and down-beat out-of-season seaside town which is obviously Mablethorpe. The central character is George Fowler, a mobster who has made a living out of distributing porn movies, but has crossed the wrong people, and needs somewhere to hide up for a while. Rather like his creator, Fowler is in the darkest of dark places, and the novel ends in brutal and surreal fashion on a deserted Lincolnshire beach, with the wind howling in from the north sea as Fowler meets his maker in the remains of an RAF bombing target.