No fictional character has been so imitated, transposed to another century, Steampunked, turned into an American, or subject to pastiche than Sherlock Holmes. In my late teens I became aware of a series of stories by Adrian Conan Doyle (the author’s youngest son) and I thought they were rather good. Back then, I was completely unaware that the Sherlock Holmes ‘industry’ was running even while new canonical stories were still being published in the 1890s. Few of them survive inspection, and I have to say I am a Holmes purist. I watched one episode of Benedict Cumberbatch’s ‘Sherlock’, and then it was dead to me. As for Robert Downey Jr, don’t (as they say)”get me started.” For me, the film/TV apotheosis was Jeremy Brett, but I have a warm place in my heart for the 1950s radio versions starring Carleton Hobbs and Norman Shelley.

How, then, how does this latest manifestation of The Great Man hold up? The narrative has a pleasing symmetry. The good Doctor is, as ever, the storyteller, but as the book title suggests there is another element. Alternate chapters are seen through the eyes of a man called Moran who is, if you like, Moriarty’s Watson. Gareth Rubin’s Watson is pretty much the standard loyal friend, stalwart and brave, if slightly slow on the uptake. Moran’s voice is suitably different, peppered with criminal slang and much more racy.

The case that draws Holmes into action is rather like The Red Headed League, in that a seemingly odd but ostensibly harmless occurrence (a red haired man being employed to copy out pages of an encyclopaedia) is actually cover for something far more sinister. In this case, a young actor has been hired to play Richard III in a touring production. He comes to Holmes because he is convinced that the small audiences attending each production are actually the same people each night, but disguised differently each time.

Meanwhile, Moriarty has become involved in a turf war involving rival gangsters, and there is an impressive body count, mostly due to the use of a terrifying new invention, the Maxim Gun. There is so much going on, in terms of plot strands, that I would be here all week trying to explain but, cutting to the chase, our two mortal enemies are drawn together after a formal opening of an exhibition at The British Museum goes spectacularly wrong when two principal guests are killed by a biblical plague of peucetia viridans. Google it or, if you are an arachnophobe, best give it a miss.

Long story short, three of the men who led the archaeological dig that produced the exhibits for the aborted exhibition at the BM are now dead, killed in some sort of international conspiracy. It is worth reminding readers that as the 19thC rolled into the 20thC, the pot that eventually boiled over in 1914 was already simmering. Serbian nationalism, German territorial ambitions, the ailing empires of the Ottomans and Austria Hungary, and the gathering crisis in Russia all made for a toxic mix. This novel is not what I would call serious historical fiction. It is more of a melodramatic – and very entertaining – romp, and none the worse for that, but Gareth Rubin makes us aware of the real-life dangerous times inhabited by his imaginary characters.

Eventually Holmes, Watson, Moriarty and Moran head for Switzerland as uneasy allies, for it is in these mountains that the peril lurks, the conspiracy of powerful men that threatens to change the face of Europe. They fetch up in Grenden, a strange village in the shadow of the Jungfrau and it is here, in a remarkably palatial hotel given the location, they are sure they have come to the place from which the plot will be launched. By this stage the novel has taken a distinctly Indiana Jones turn, with secret passages, and deadly traps (again involving spiders).

This is great fun, with all the erudition one would expect from The Great Consulting Detective and with a rip-roaring adventure thrown in for good measure. It is published by Simon & Schuster, and will be available at the end of September.

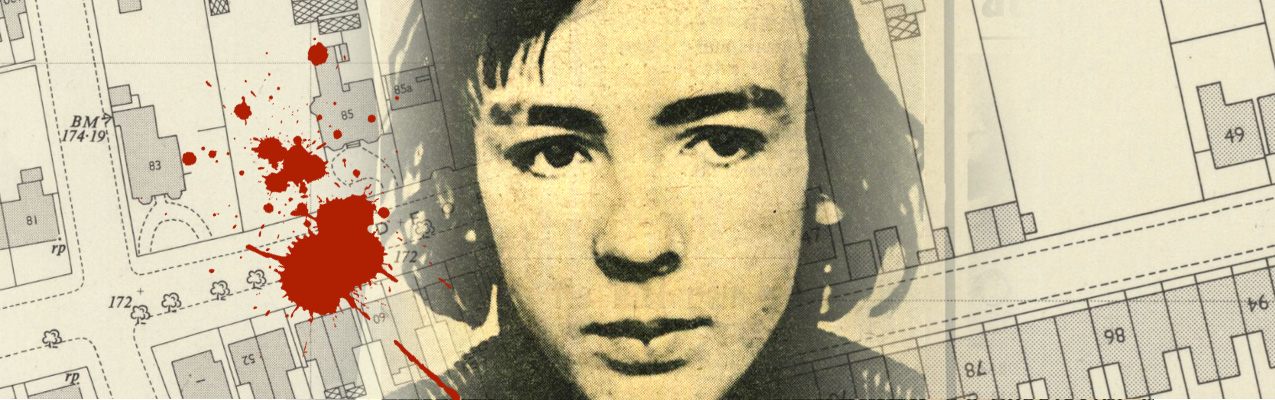

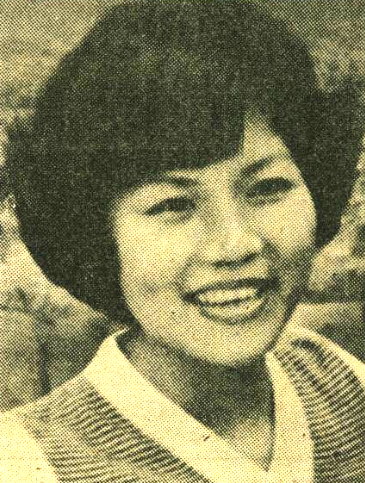

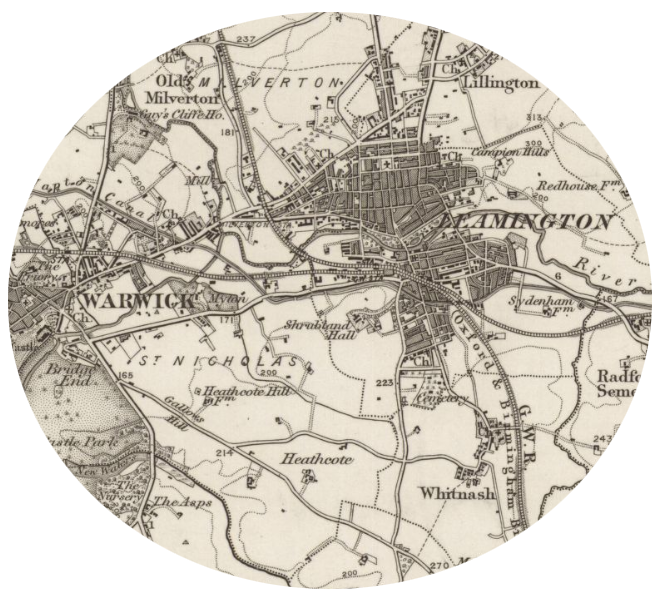

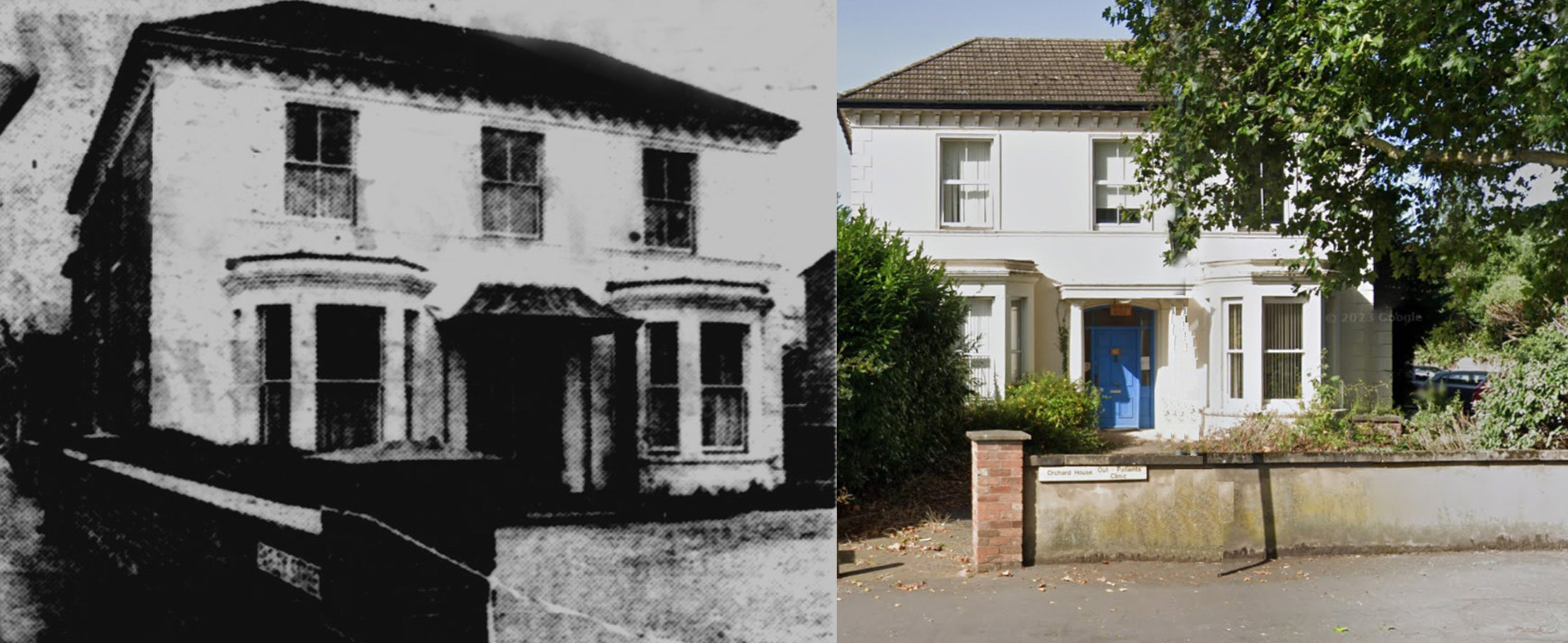

SO FAR: In the early hours of Monday 2nd February 1976, the butchered body of Chinese nurse Tze Yung Tong (left) was found in her room in a nurses’ hostel at 83 Redford Road, Leamington Spa. Other young women had heard noises in the night, but had been too terrified to venture beyond their locked doors. We can talk about ships passing in the night, in the sense of two people meeting once, but never again. Tze Yung Tong was to meet her killer just the one fatal time.

SO FAR: In the early hours of Monday 2nd February 1976, the butchered body of Chinese nurse Tze Yung Tong (left) was found in her room in a nurses’ hostel at 83 Redford Road, Leamington Spa. Other young women had heard noises in the night, but had been too terrified to venture beyond their locked doors. We can talk about ships passing in the night, in the sense of two people meeting once, but never again. Tze Yung Tong was to meet her killer just the one fatal time.

Despite his palpable guilt, Reilly was endlessly remanded, made numerous appearances before local magistrates, but eventually had brief moment in a higher court. At Birmingham Crown Court in December, Mr Justice Donaldson (right) found him guilty of murder, and sentenced him to life, with a minimum tariff of 20 years.In 1997, a regional newspaper did a retrospective feature on the case. By then, the police admitted that he had already been released. Do the sums. Reilly, the Baby-Faced Butcher may still be out there. He will only be in his late 60s. Ten years younger than me. One of the stranger aspects of this story is that, as far as I can tell, at no time did solicitors and barristers working to defend Reilly ever suggest that his actions were that of someone not in his right mind. By contrast, in an earlier shocking Leamington case in 1949,

Despite his palpable guilt, Reilly was endlessly remanded, made numerous appearances before local magistrates, but eventually had brief moment in a higher court. At Birmingham Crown Court in December, Mr Justice Donaldson (right) found him guilty of murder, and sentenced him to life, with a minimum tariff of 20 years.In 1997, a regional newspaper did a retrospective feature on the case. By then, the police admitted that he had already been released. Do the sums. Reilly, the Baby-Faced Butcher may still be out there. He will only be in his late 60s. Ten years younger than me. One of the stranger aspects of this story is that, as far as I can tell, at no time did solicitors and barristers working to defend Reilly ever suggest that his actions were that of someone not in his right mind. By contrast, in an earlier shocking Leamington case in 1949,

When Lady Frideswide is found dead beside the footpath between The Lazar House and the brewery, the Bishop’s Seneschal, Sir John Bosse is sent for and he begins his investigation. His first conclusion is that Frideswide was poisoned, by deadly hemlock being added to flask of ale, found empty and discarded on the nearby river bank. He has the method. Now he must discover means and motive. Bosse is a shrewd investigator, and he realises that Frideswide was not, by nature, a charitable woman, therefore was the valuable gift of ale a penance for a previous sin? Pondering what her crime may have been, he rules out acts of violence, as they would have been dealt with by the authorities. Robbery? Hardly, as the de Banlon family are wealthy. He has what we would call a ‘light-bulb moment’, although that metaphor is hardly appropriate for the 14th century. Frideswide, despite her unpleasant manner, was still extremely beautiful, so Bosse settles for the Seventh Commandment. But with whom did she commit adultery?

When Lady Frideswide is found dead beside the footpath between The Lazar House and the brewery, the Bishop’s Seneschal, Sir John Bosse is sent for and he begins his investigation. His first conclusion is that Frideswide was poisoned, by deadly hemlock being added to flask of ale, found empty and discarded on the nearby river bank. He has the method. Now he must discover means and motive. Bosse is a shrewd investigator, and he realises that Frideswide was not, by nature, a charitable woman, therefore was the valuable gift of ale a penance for a previous sin? Pondering what her crime may have been, he rules out acts of violence, as they would have been dealt with by the authorities. Robbery? Hardly, as the de Banlon family are wealthy. He has what we would call a ‘light-bulb moment’, although that metaphor is hardly appropriate for the 14th century. Frideswide, despite her unpleasant manner, was still extremely beautiful, so Bosse settles for the Seventh Commandment. But with whom did she commit adultery?

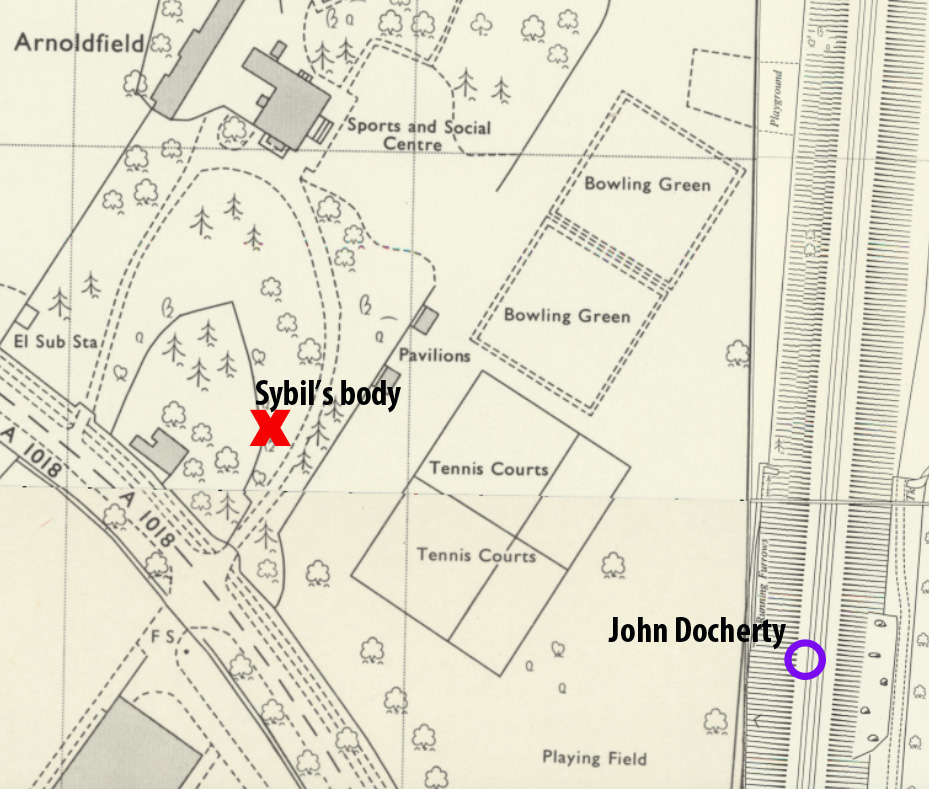

SO FAR: 10th August, 1954. Just after 11.00 am. In the drive leading up to the former mansion known as Arden Field just outside Grantham, the body of 24 year-old Sybil Hoy was found. She had been brutally murdered. Her body was taken away to the mortuary, and police began searching for the weapon. Just a few hundred yards away, across the Kings School playing fields, was the railway embankment that carried the London to Edinburgh main line. A railway lengthman (an employee responsible for walking a particular stretch of line checking for problems) had just climbed the embankments, and stood back as the London to Edinburgh service known as The Elizabethan Express thundered past.

SO FAR: 10th August, 1954. Just after 11.00 am. In the drive leading up to the former mansion known as Arden Field just outside Grantham, the body of 24 year-old Sybil Hoy was found. She had been brutally murdered. Her body was taken away to the mortuary, and police began searching for the weapon. Just a few hundred yards away, across the Kings School playing fields, was the railway embankment that carried the London to Edinburgh main line. A railway lengthman (an employee responsible for walking a particular stretch of line checking for problems) had just climbed the embankments, and stood back as the London to Edinburgh service known as The Elizabethan Express thundered past.

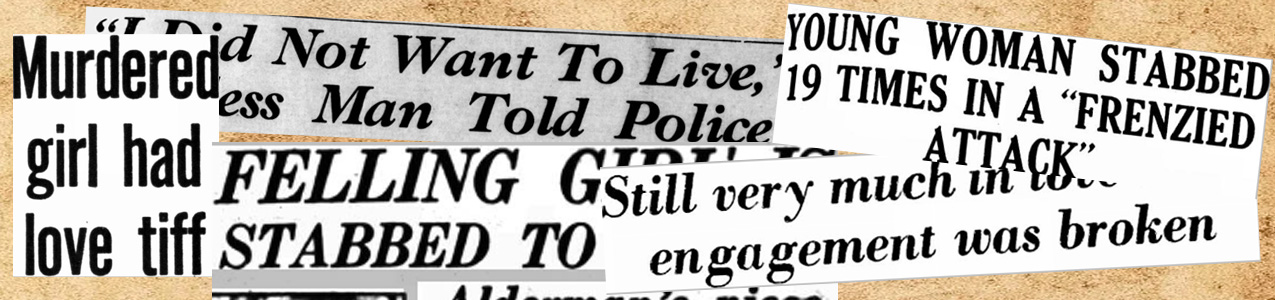

After her body had been probed and prodded by investigators, it was eventually returned to her mother and father. God, or whoever controls the heavens, was not best pleased, because a violent storm rained down on the many mourners at the Victorian Christ Church in Felling

After her body had been probed and prodded by investigators, it was eventually returned to her mother and father. God, or whoever controls the heavens, was not best pleased, because a violent storm rained down on the many mourners at the Victorian Christ Church in Felling