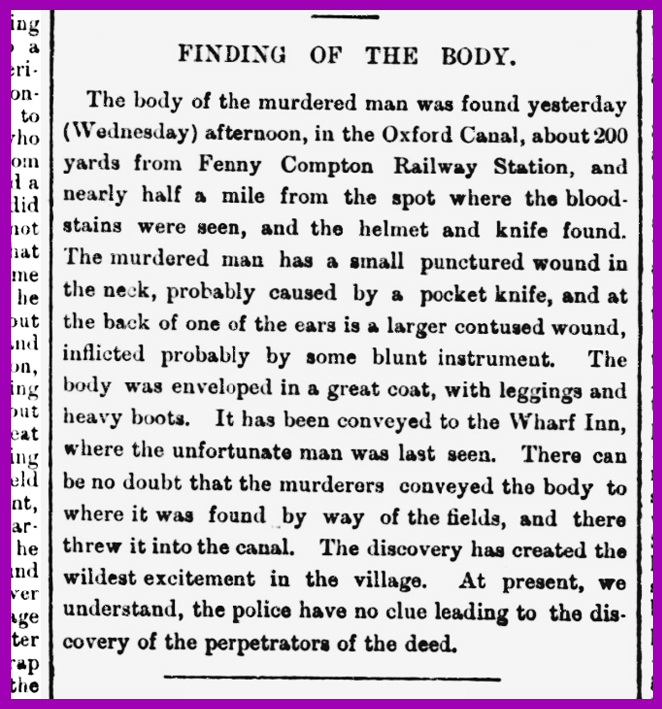

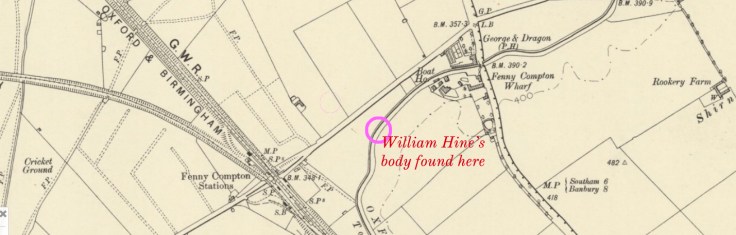

SO FAR: Fenny Compton, February 1886. Police Constable William Hine has not been seen since he left The George and Dragon inn on the evening of 15th February. Foul play is suspected, but his colleagues in the Warwickshire constabulary have found no trace of him. The Banbury Guardian, of Thursday 25th February broke this news:

There was a Coroner’s Inquest. Hine had been dealt a savage blow to the head, which had stunned him but the cause of death was something much more sinister – and puzzling. He had two almost surgical knife wounds in the neck, and it was speculated that he had been held down and bled out.

“The medical evidence went to show that the fatal wound in the neck had been inflicted with scientific accuracy, and that probably the deceased was held down on the ground while it was indicted.”

On 6th March, The Leamington Spa Courier reported on the wintry funeral of the murdered officer:

“The remains of the murdered constable, Hine, of Fenny Compton, were interred in the Borough Cemetery, Stratford-on-Avon on Monday. More inclement weather could not possibly have been experienced. Snow had been falling for several hours, and lay upon the streets and roads to the depth of about two feet. On the outskirts of the town the snowdrifts were, in places, from three to four feet deep. Such unpropitious weather naturally militated against so large attendance of spectators as had been anticipated. Many who had intended coming from a distance were compelled to forego their intention, some of the country roads being almost impassible.”

“The hearse conveying the body of the murdered man to Stratford left the Wharf Inn, Fenny Compton, about 8 am. The journey to Stratford, nineteen miles, was accomplished with difficulty, and in the face of a blinding snowstorm. At Kineton, ten miles distant, it was found necessary to engage a third horse, the roads in places being blocked with snow. Just prior to leaving Fenny Compton a very beautiful floral wreath, composed of white camellias and maidenhair ferns, was placed upon the coffin by Mr Perry, of Burton Dasset, magistrate for that division. The hearse arrived at Stratford shortly before noon. By that time a large number of police, representing every division in the county, had assembled in the open space near Clopton Bridge.”

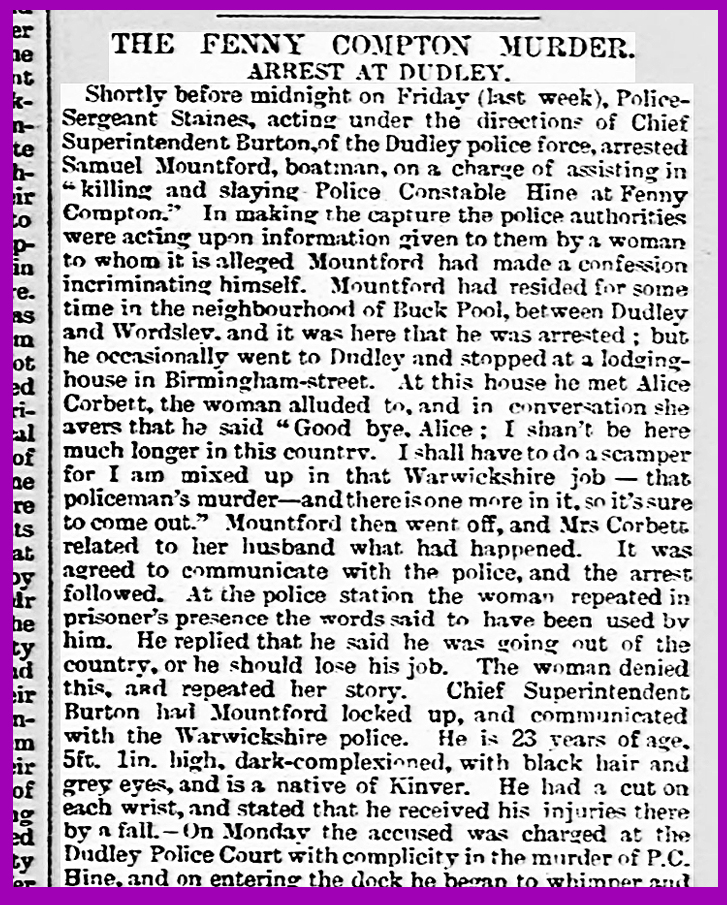

The search for those who had murdered William Hine – and opinion was that there was more than one assailant – went on until the trail grew as cold the weather on the day he was buried. There was a bizarre interlude when a bargee from the Black Country was arrested for the murder, having confessed involvement in it to a woman friend, who passed this on to the police:

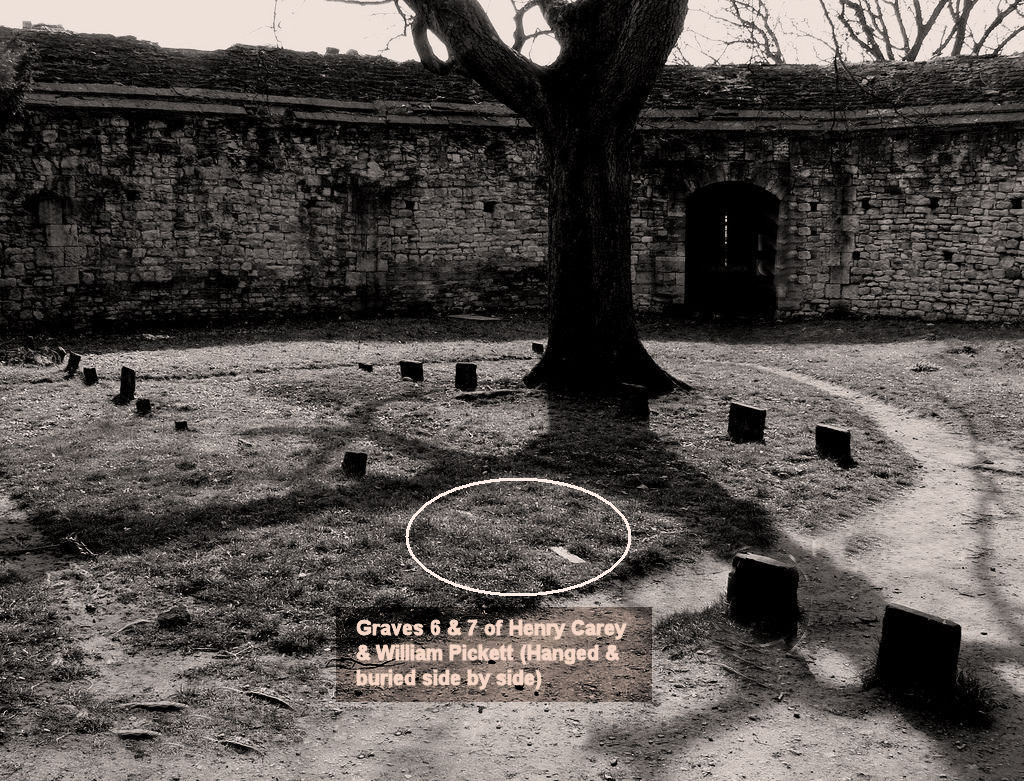

In court, Mountford then vehemently denied that he had been involved, but gave no reason for his extraordinary confession. He was released without charge, and the police never explained why they discounted his confession. A year later, another “clue” emerged, as reported by the Kenilworth Advertiser:

“The police have discovered blood-stained clothes hidden in a garden at Cropredy village, adjoining Fenny Compton, and it is believed that they belong to the men who murdered Police-constable Hine in February last year. Two men in prison at Oxford are suspected. The night after the murder a woman at Cropredy noticed the blood-stains on the inspected men’s clothes, and it is said they threatened to “do” for her husband if she mentioned the circumstance. The woman is since dead, but made a statement before death.”

The death of William Hine is perhaps not the most infamous unsolved murder in Warwickshire history. That dubious accolade has to belong to the killing of Charles Walton on 14th February 1945. To read that story, click this link. There is, however, at least one similarity, and that is the location and its ambience. Lower Quinton is twenty miles away from Fenny Compton, but is in that self-same part of rural south Warwickshire, a countryside untouched by heavy industry and intense urbanisation. Both locations remain thinly populated, lightly policed, and share a population which, back in the day before mass media and the internet, tended to keep themselves to themselves, and had a residual suspicion of strangers. There was always the suspicion that Walton’s death was somehow connected with witchcraft; there was no hint of this in the killing of William Hine, but the peculiar nature of the wounds on his throat was never explained away.

It is abundantly clear to me that despite the best efforts of the police, there were people who knew who had killed Charles Walton, but they took their silence to the grave. My best guess is that same applies to Fenny Compton in 1886. I believe William Hine was killed by local criminals – probably poachers and livestock thieves – who local people knew and – most importantly – feared. A charitable fund was raised for Hine’s widow and children. There was something of a scare in September 1887, when the Leamington bank of Greenway, Smith and Greenway collapsed, and it was rumoured that the Hine fund – close to £80,000 in modern money – had been in their keeping. This rumour proved untrue and the fund paid out until Emily Hine (left) died in 1924. She never remarried, and lived in Shottery for the rest of her life. A new headstone was erected in the memory of William and Emily in more recent times.

It is abundantly clear to me that despite the best efforts of the police, there were people who knew who had killed Charles Walton, but they took their silence to the grave. My best guess is that same applies to Fenny Compton in 1886. I believe William Hine was killed by local criminals – probably poachers and livestock thieves – who local people knew and – most importantly – feared. A charitable fund was raised for Hine’s widow and children. There was something of a scare in September 1887, when the Leamington bank of Greenway, Smith and Greenway collapsed, and it was rumoured that the Hine fund – close to £80,000 in modern money – had been in their keeping. This rumour proved untrue and the fund paid out until Emily Hine (left) died in 1924. She never remarried, and lived in Shottery for the rest of her life. A new headstone was erected in the memory of William and Emily in more recent times.

CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW

FOR MORE WARWICKSHIRE MURDERS

William Hine was born in the hamlet of Ingon, just north of Stratford on Avon, on 7th September, 1857, although his birthplace is listed on the 1861 census as nearby Hampton Lucy. He and his parents, with his brother and sister are listed as living at 2 Gospel Oak. He married Emily Edwards on 17th November 1880 in Stratford. Earlier that year, Hine had joined the police force. By February 1886 they had three children. By then, Hine was serving as Police Constable in the village of Fenny Compton.

William Hine was born in the hamlet of Ingon, just north of Stratford on Avon, on 7th September, 1857, although his birthplace is listed on the 1861 census as nearby Hampton Lucy. He and his parents, with his brother and sister are listed as living at 2 Gospel Oak. He married Emily Edwards on 17th November 1880 in Stratford. Earlier that year, Hine had joined the police force. By February 1886 they had three children. By then, Hine was serving as Police Constable in the village of Fenny Compton.

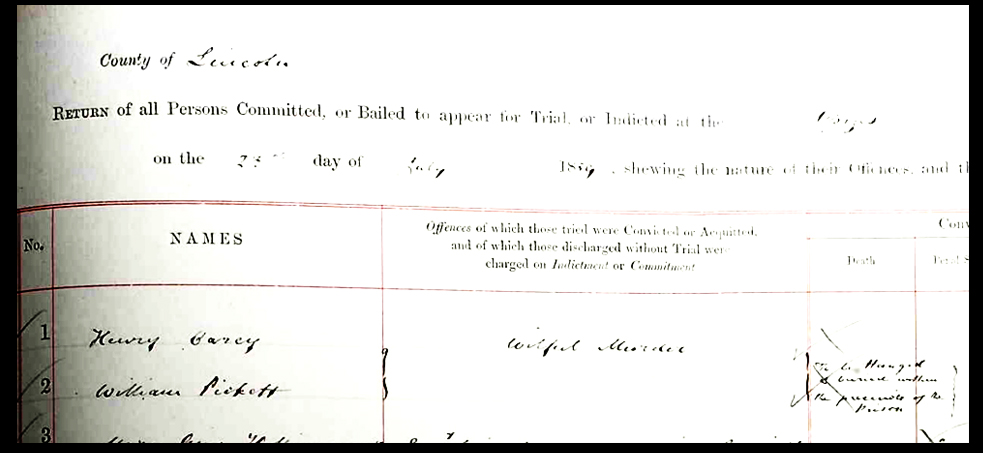

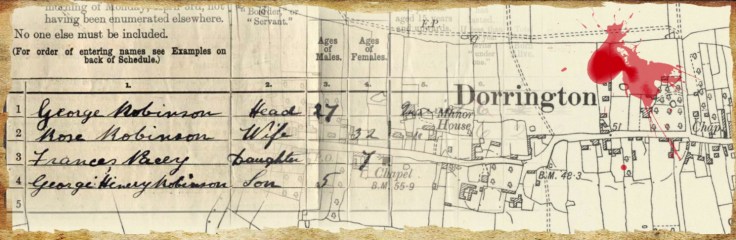

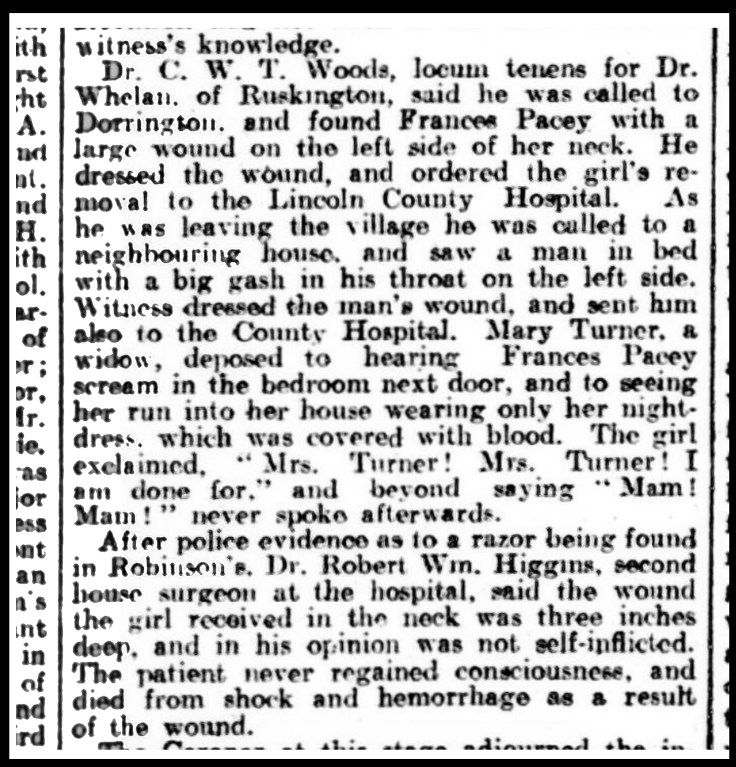

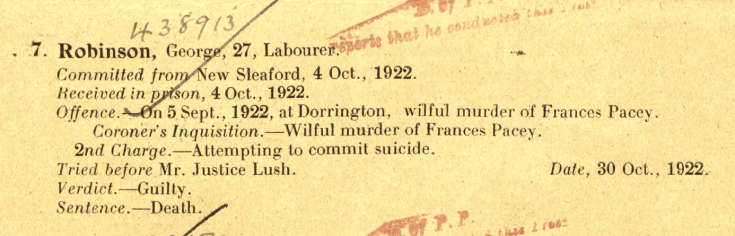

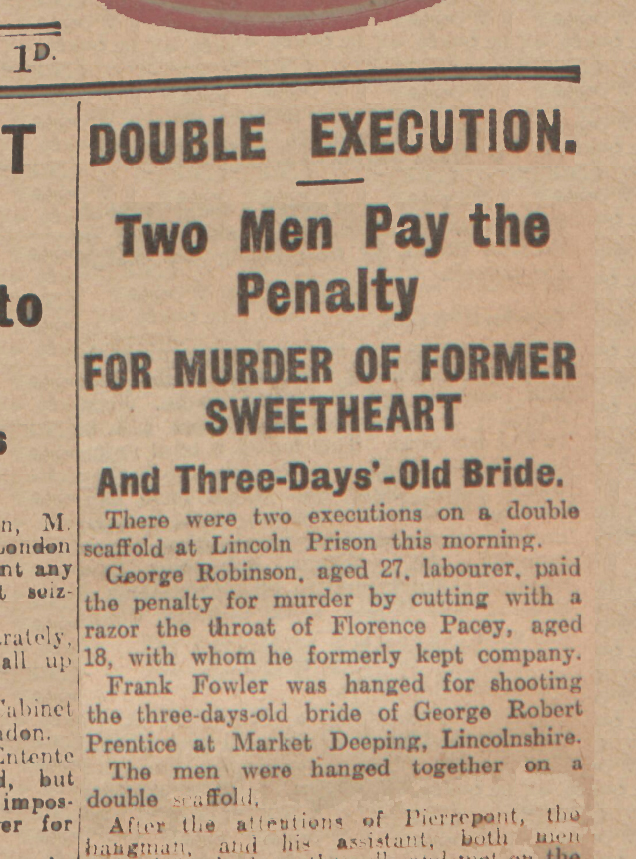

If ever a Lincolnshire village merited the description ‘sleepy’, it might be Dorrington. A few miles north of Sleaford, it sits between today’s B1188 and the railway line between Peterborough and Lincoln.

If ever a Lincolnshire village merited the description ‘sleepy’, it might be Dorrington. A few miles north of Sleaford, it sits between today’s B1188 and the railway line between Peterborough and Lincoln.

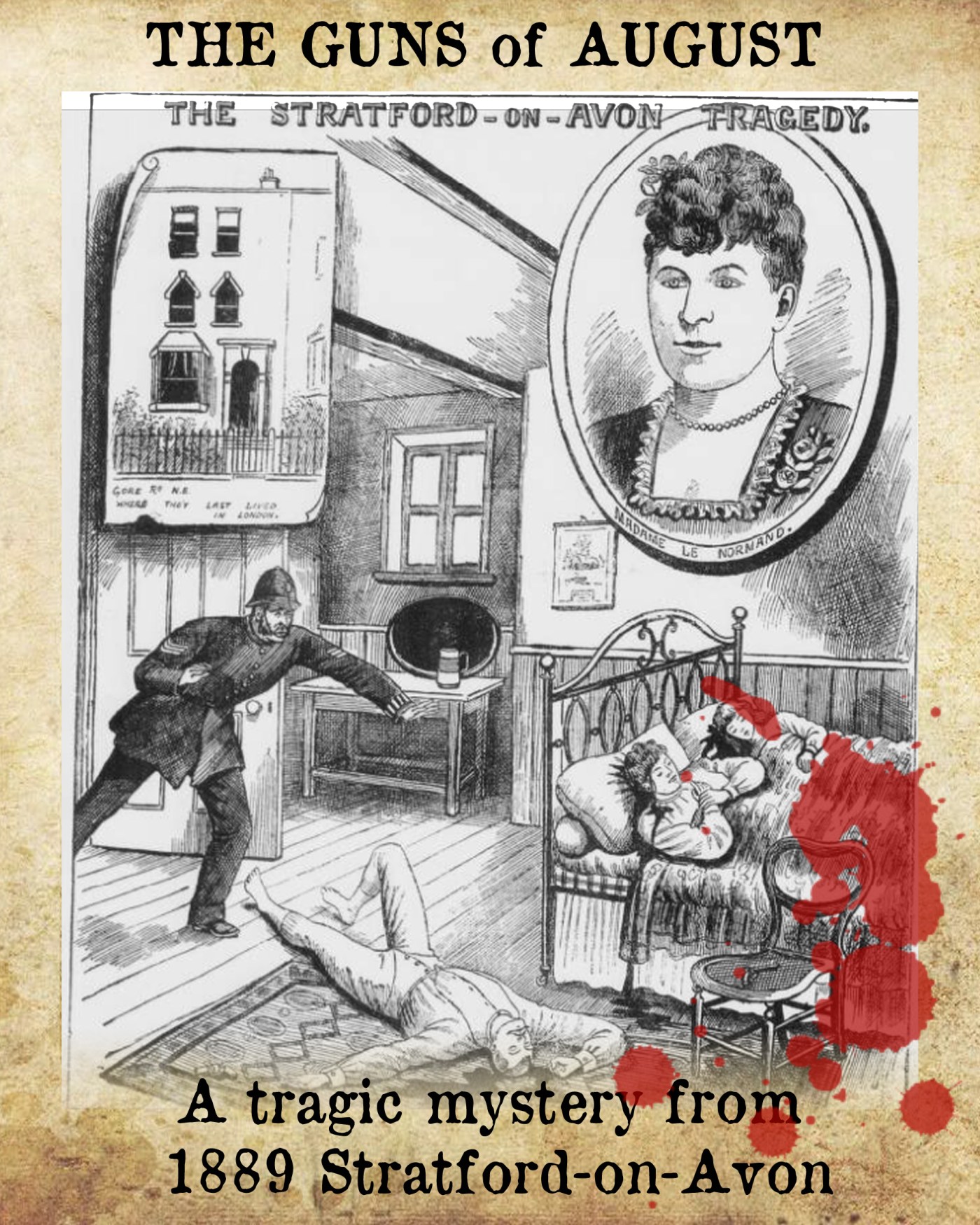

What threw the investigation on its head was the fact that the woman who died in that Stratford cottage was not von Gamsenfels wife, although the dead child was probably his. By examining the dead man’s possessions, the police discovered that his legal wife was a Mrs Rosanna Lachmann von Gamsenfels, and that their marriage was somewhat unusual. He was absent from the family home for months on end, but always gave his wife money for the upkeep of their son. Mrs Lachmann von Gamsenfels traveled up to Stratford to identify her husband’s body, but was either unable- or unwilling – to put names to the dead woman and girl. Try as they may, the authorities were unable to put names to the woman and girl who were shot dead on that fateful Monday morning. Artists’ impressions of ‘Mrs von Gamsenfels” were published (left) but she and her daughter left the world unknown, and if anyone mourned them, they kept silent.

What threw the investigation on its head was the fact that the woman who died in that Stratford cottage was not von Gamsenfels wife, although the dead child was probably his. By examining the dead man’s possessions, the police discovered that his legal wife was a Mrs Rosanna Lachmann von Gamsenfels, and that their marriage was somewhat unusual. He was absent from the family home for months on end, but always gave his wife money for the upkeep of their son. Mrs Lachmann von Gamsenfels traveled up to Stratford to identify her husband’s body, but was either unable- or unwilling – to put names to the dead woman and girl. Try as they may, the authorities were unable to put names to the woman and girl who were shot dead on that fateful Monday morning. Artists’ impressions of ‘Mrs von Gamsenfels” were published (left) but she and her daughter left the world unknown, and if anyone mourned them, they kept silent.

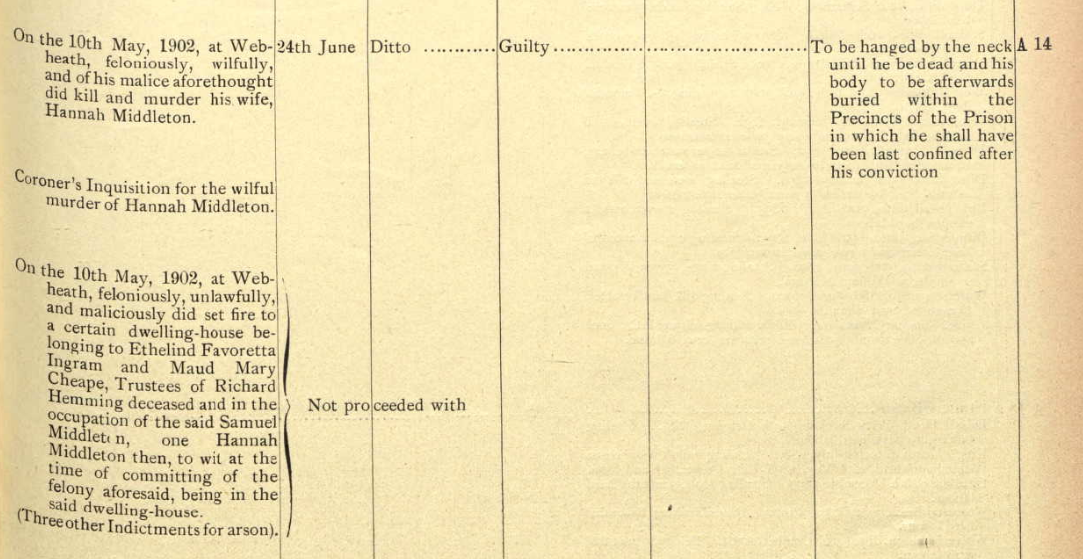

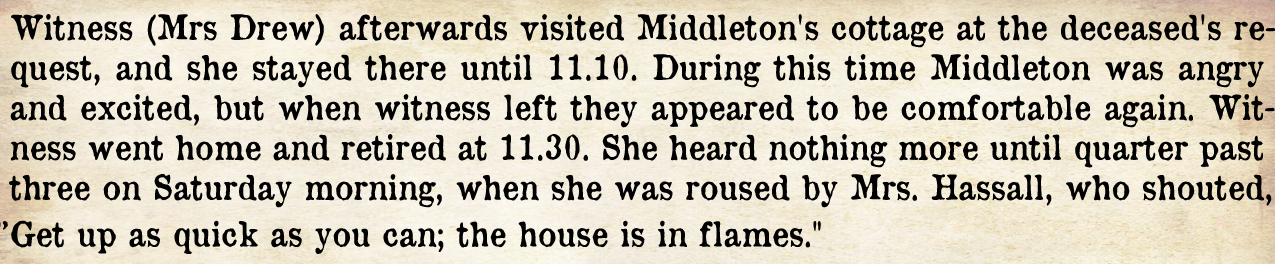

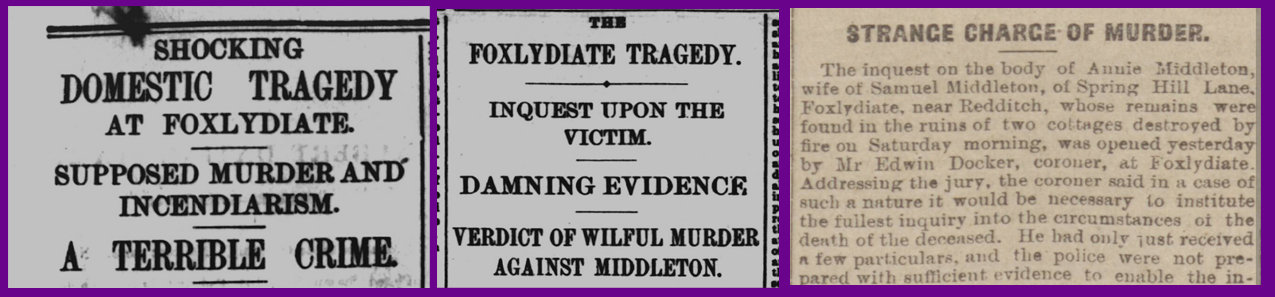

SO FAR: On the evening of 10th/11th May 1902, Foxlydiate couple Samuel and Hannah Middleton had been having a protracted and violent argument. At 3.30 am the alarm was given that their cottage was on fire. When the police were eventually able to enter what was left of the cottage there was little left of Hannah Middleton (left, in a newspaper likeness) but a charred corpse. Samuel Middleton was arrested on suspicion of murdering his wife. The coroner’s inquest heard that one of the technical problems was that Hannah Middleton’s body had been so destroyed by the fire that a proper examination was impossible.

SO FAR: On the evening of 10th/11th May 1902, Foxlydiate couple Samuel and Hannah Middleton had been having a protracted and violent argument. At 3.30 am the alarm was given that their cottage was on fire. When the police were eventually able to enter what was left of the cottage there was little left of Hannah Middleton (left, in a newspaper likeness) but a charred corpse. Samuel Middleton was arrested on suspicion of murdering his wife. The coroner’s inquest heard that one of the technical problems was that Hannah Middleton’s body had been so destroyed by the fire that a proper examination was impossible.

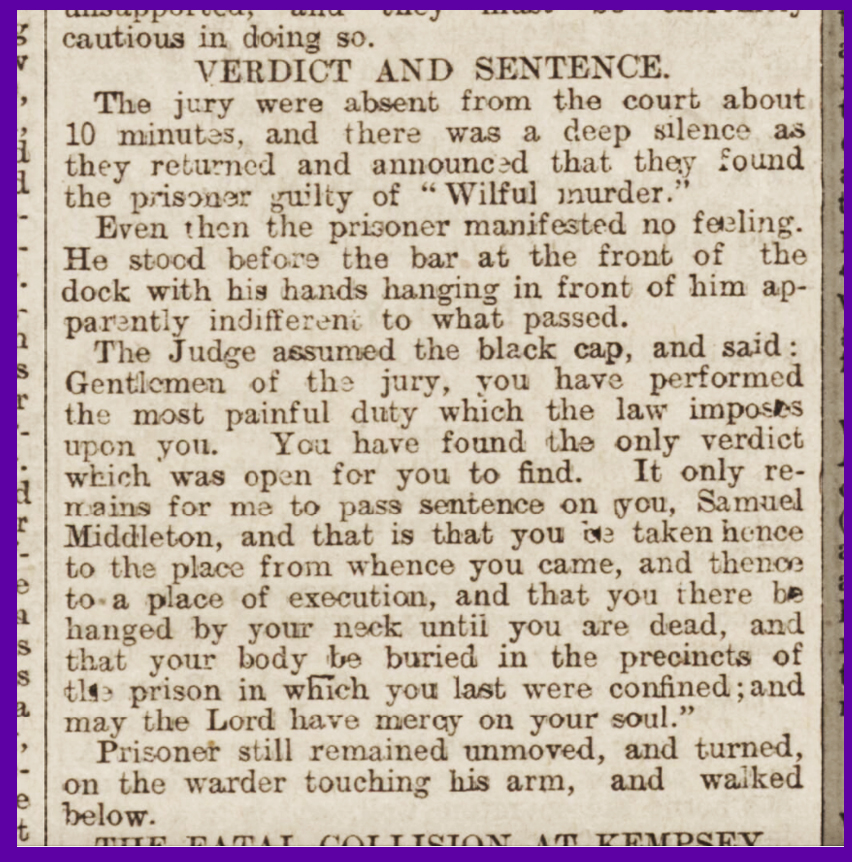

Samuel Middleton was sent for trial at the summer assizes in Worcester. Assize courts were normally held three or four times a year in the county towns around the country, and were presided over by a senior judge. These courts were were for the more serious crimes which could not be dealt with my local magistrate courts. At the end of June, Samuel Middleton stood before Mr Justice Wright (left) and the proceedings were relatively short. The only fragile straw Middleton’s defence barristers could cling to was the lesser charge of manslaughter. Middleton had repeatedly said, in various versions, that his wife had clung to him with the intention of doing him harm – “She would have bit me to pieces, so I had to finish her.” It was clear to both judge and jury, however, that Middleton had battered his wife over the head with a poker, and then set fire to the cottage in an attempt to hide the evidence. Mr Justice Wright delivered the inevitable verdict with due solemnity.

Samuel Middleton was sent for trial at the summer assizes in Worcester. Assize courts were normally held three or four times a year in the county towns around the country, and were presided over by a senior judge. These courts were were for the more serious crimes which could not be dealt with my local magistrate courts. At the end of June, Samuel Middleton stood before Mr Justice Wright (left) and the proceedings were relatively short. The only fragile straw Middleton’s defence barristers could cling to was the lesser charge of manslaughter. Middleton had repeatedly said, in various versions, that his wife had clung to him with the intention of doing him harm – “She would have bit me to pieces, so I had to finish her.” It was clear to both judge and jury, however, that Middleton had battered his wife over the head with a poker, and then set fire to the cottage in an attempt to hide the evidence. Mr Justice Wright delivered the inevitable verdict with due solemnity.