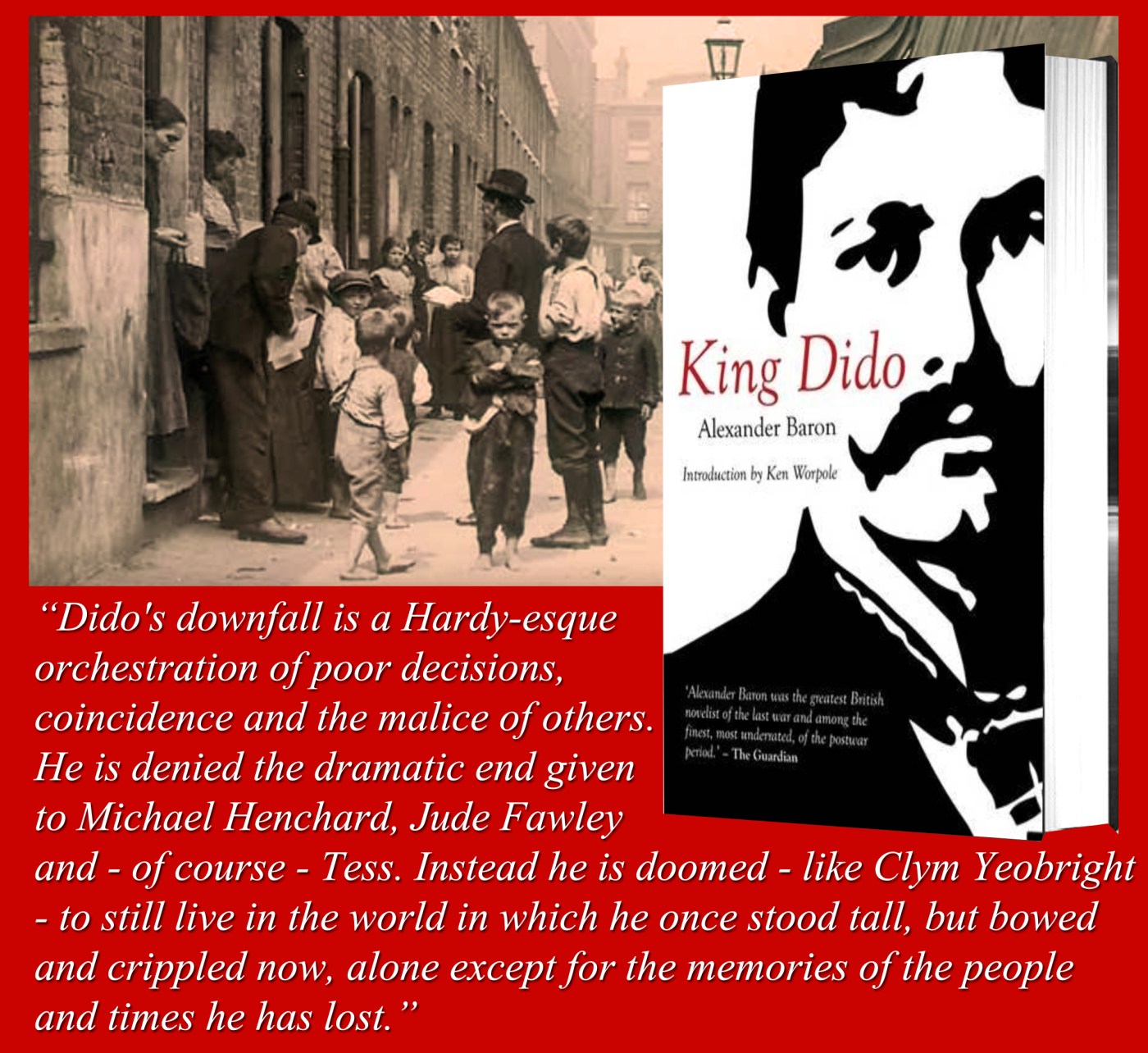

Alexander Baron (1917 – 1999) is a writer who has returned to the consciousness of the reading public in recent times because the Imperial War Museum have republished his two classic WW2 novels From The City, From The Plough, There’s No Home, and the third in the trilogy, the collection of short stories The Human KInd. His compassion and his acute awareness of the highs and lows of men and women at war have embedded the trilogy into the culture of WW2, just as the poems of Owen, Sassoon and Gurney are inescapably linked with The Great War. King Dido (1969) is a book of a very different kind.

We are in the East End of London, and it is the summer of 1911, not long after the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary. Dido is, by trade, a dock worker but, after a violent encounter with the district’s 1911 version of the Krays, he takes over the streets and becomes a kind of Reg. Not Ron, because Dido is not a psychopath, but the ‘tributes’ he collects make him a decent living. After a turbulent back alley encounter with a young waitress called Grace, Dido does ‘right thing’ and marries her. They live in redecorated rooms above the rag recovery business Dido’s mother runs. There has been a trend in crime fiction in recent years, which I call ‘anxiety porn’, but it is nothing new. More politely, these are known as ‘domestic thrillers.’ Mostly, they describe perfectly ordinary people whose lives gradually disintegrate, not through epic events, but because normal social tensions, misunderstandings, misplaced ambitions and tricks of fate turn their lives upside down. So it is here. Grace, blissfully unaware of how Dido earns his money, tries to put her feet on the next series of rungs in the ladder that leads to gentrification. However, the family’s journey on the board game of life becomes, via the snakes, a downward one, and it is a painful descent.

Baron grew up as Joseph Alexander Bernstein in Hackney, but he was actually born In Maidenhead, his mother having been evacuated there as a result of Zeppelin raids on London. His father was a master furrier, so it is clear that there is nothing autobiographical about his characterisation of Dido Peach. What is evident in the book is that Baron was aware of the existence of subtle strata within the East End poor. By 1911 the Huguenots had long since moved away, leaving such places as Christ Church Spitalfields and the elegant houses in Fournier Street as their memorials. There remained what could be called the ‘dirt’ poor, and then the ‘genteel’ poor – such as Mrs Peach and her family. What doesn’t feature in the novel, but was exactly contemporaneous, was the upsurge in activity by Eastern European activists, mostly exiles from Russia. The Houndsditch Murders and the resultant Siege of Sidney Street was that same year, while The Tottenham Outrage had been two years earlier. Both events remain writ large in East End history.

In the end, Dido’s downfall is a Hardy-esque orchestration of poor decisions, coincidence and the malice of others. He is denied the dramatic end given to Michael Henchard, Jude Fawley and – of course – Tess. Instead he is doomed – like Clym Yeobright – to still live in the world in which he once stood tall, but bowed and crippled now, alone except for the memories of the people and times he has lost. Baron’s prose here, just as in his better known books, is vivid, clear and full of insights.

The Big Sleep was published in 1939, but the iconic film version, directed by Howard Hawks, wasn’t released until 1946. Are the dates significant? There is an obvious conclusion, in terms of what took place in between, but I am not sure if it is the correct one. The novel introduced Philip Marlowe to the reading public and, my goodness, what an introduction. The second chapter, where Los Angeles PI Marlowe goes to meet the ailing General Sternwood who is worried about his errant daughters, contains astonishing prose. Sternwood sits, wheelchair-bound, in what we Brits call a greenhouse. Marlowe sweats as Sternwood tells him:

The Big Sleep was published in 1939, but the iconic film version, directed by Howard Hawks, wasn’t released until 1946. Are the dates significant? There is an obvious conclusion, in terms of what took place in between, but I am not sure if it is the correct one. The novel introduced Philip Marlowe to the reading public and, my goodness, what an introduction. The second chapter, where Los Angeles PI Marlowe goes to meet the ailing General Sternwood who is worried about his errant daughters, contains astonishing prose. Sternwood sits, wheelchair-bound, in what we Brits call a greenhouse. Marlowe sweats as Sternwood tells him:

The book began with an optimistic Marlowe:

The book began with an optimistic Marlowe:

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it. Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence.

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence.

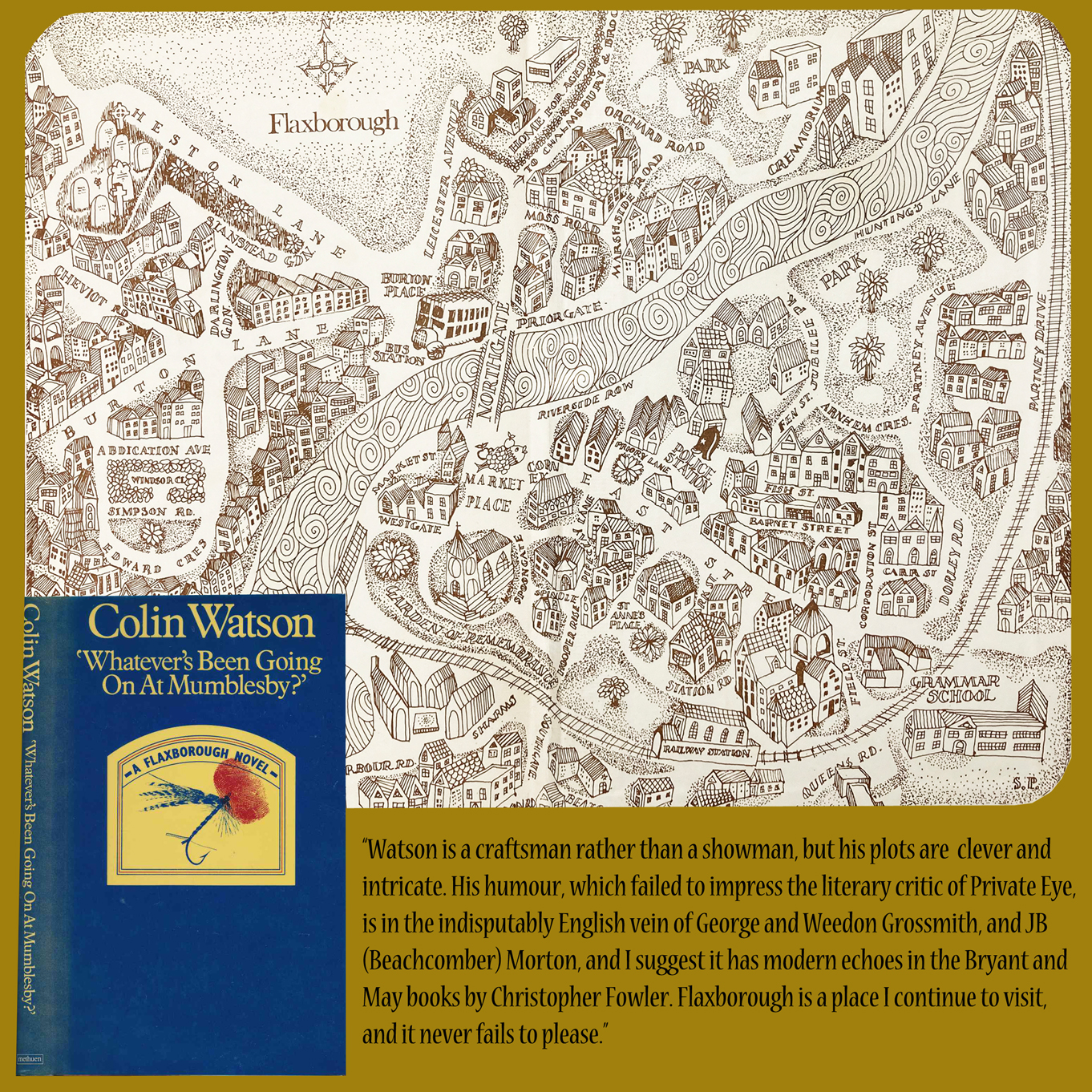

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

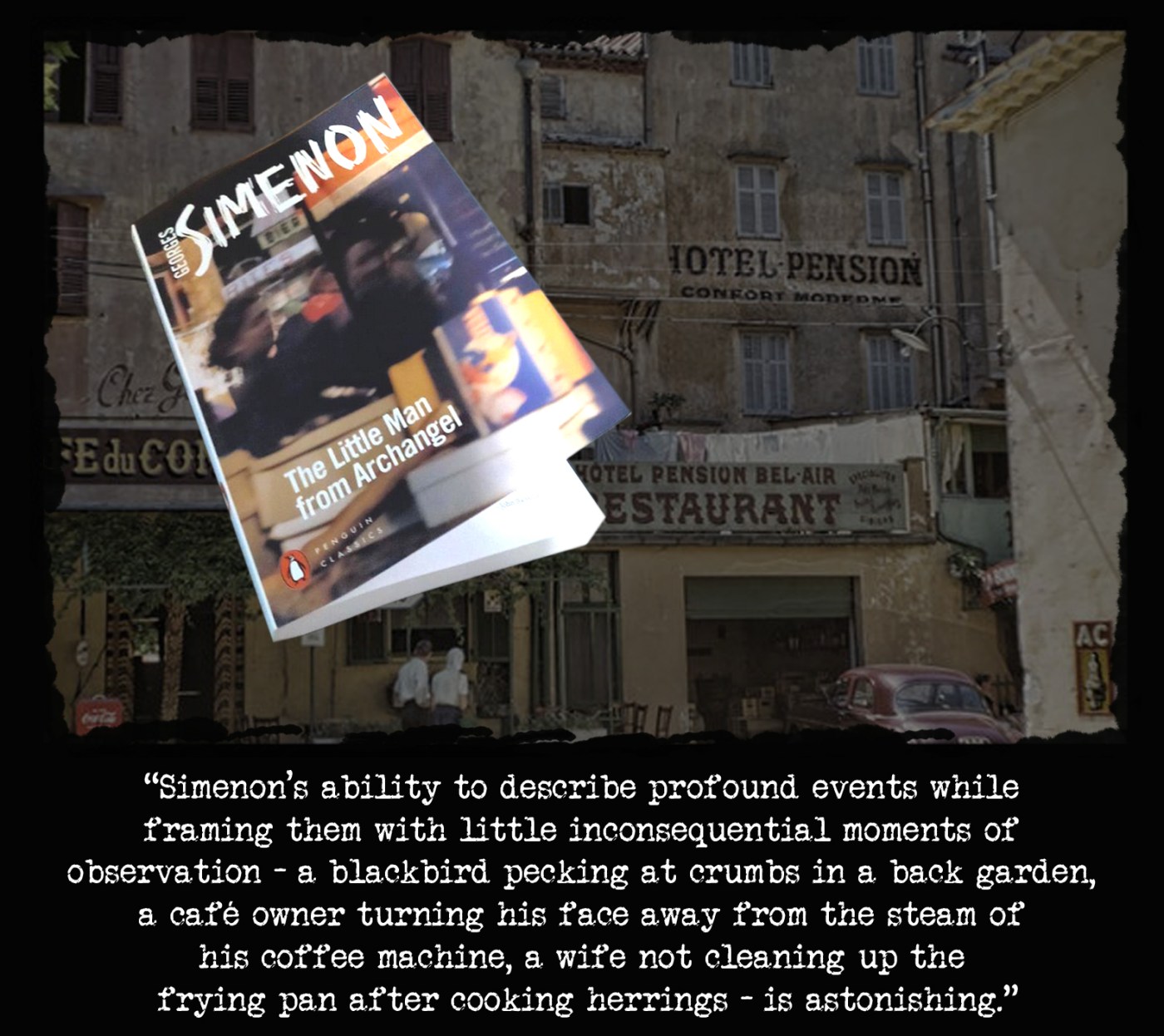

We are in an anonymous little town in the Berry region of central France, and it is the middle years of the 1950s. Jonas Milk is a mild-mannered dealer in second hand books. His shop, his acquaintances, the c

We are in an anonymous little town in the Berry region of central France, and it is the middle years of the 1950s. Jonas Milk is a mild-mannered dealer in second hand books. His shop, his acquaintances, the c Jonas Milk has a wife. Two years earlier he had converted to Catholicism and married Eugénie Louise Joséphine Palestri – Gina – a voluptuous and highly sexed woman sixteen years his junior. No doubt the frequenters of the Vieux-Marché have their views on this marriage, but they are polite enough to keep their opinions to themselves, at least when Jonas is within earshot. But then Gina disappears, taking with her no bag or change of clothing. The one thing she does take, however, is a selection of a very valuable stamp collection that Jonas has put together over the years, not through major purchases from dealers, but through his own obsessive examination of relatively commonplace stamps, some of which turn out to have minute flaws, thus making their value to other collectors spiral to tens of thousands of francs.

Jonas Milk has a wife. Two years earlier he had converted to Catholicism and married Eugénie Louise Joséphine Palestri – Gina – a voluptuous and highly sexed woman sixteen years his junior. No doubt the frequenters of the Vieux-Marché have their views on this marriage, but they are polite enough to keep their opinions to themselves, at least when Jonas is within earshot. But then Gina disappears, taking with her no bag or change of clothing. The one thing she does take, however, is a selection of a very valuable stamp collection that Jonas has put together over the years, not through major purchases from dealers, but through his own obsessive examination of relatively commonplace stamps, some of which turn out to have minute flaws, thus making their value to other collectors spiral to tens of thousands of francs.