An awareness of the power and influence of the English landscape is central to the writings of so many of my favourite crime writers, let alone books by literary giants such as Eliot, Dickens and Hardy. In no particular order Phil Rickman’s Merrily Watkins novels would be diminished without the brooding power of the Welsh Marches and the haunting legacy of forgotten settlements and abandoned Victorian chapels; the Philip Dryden novels of Jim Kelly are all the more intriguing due to their being set in the inward-looking hamlets and distrustful communities of the Cambridgeshire Fens. Cities have landscapes, too; Chris Nickson’s Leeds and the ancient palimpsest of London’s long history as revealed in the late Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May novels are vital parts of the narrative process.

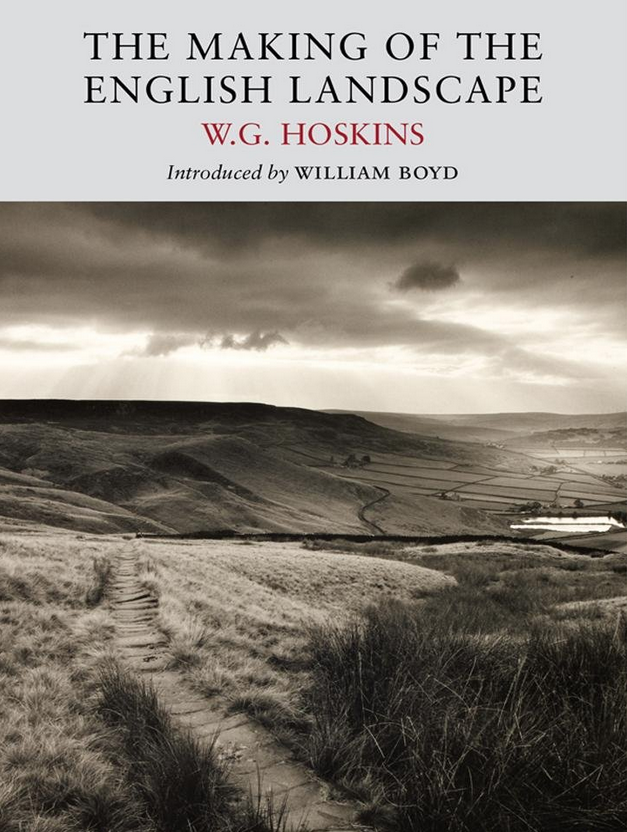

WG Hoskins walked and drove the length and breadth of post-war England, and came up with a magisterial account of how our country was shaped and created.The relentless speed of change meant that Hoskins’ book was out of date almost before print copies were on the shelves in 1955. Even his revision, two decades later, has been questioned by modern writers. His historical account from the earliest human habitation to the Industrial Revolution remains set in stone, however.

Modern observers will not be slow to spot the ironies made apparent by what he writes. He laments, aided by the powerful poetry of John Clare, the destruction – by the parliamentary enclosures in the early nineteenth century – of the ancient heathlands and vast common fields. These vast open spaces were replaced by tiny fields, each bordered by impenetrable thicket hedges of hawthorne. In recent times, ecologists have, of course, railed against the grubbing up of these hedges, and the creation of endless prairies of wheat fields to satisfy modern industrialised agriculture.

Hoskins notes that the enclosure movement provoked a huge rise in the diversity of small songbirds, and the related decline of raptors. Now, it seems, that the ornithological establishment is hell-bent on on the recreation of habitats for birds like Red Kites – even if their predation means death and destruction for smaller birds. What goes around, comes around, I suppose, and I am not qualified to take a position on this debate.The socio-political ironies abound, however. Of the effects of the frantic search for coal (to power the steam driven industrial revolution) Hoskins observes:

“In the Lancashire township of Ince, there are today 23 pit shafts covering 199 acres; one large industrial slag heap covering six acres, nearly 250 acres of land underwater or marsh due to mining subsidence, another 150 acres liable to flooding and 36 disused pit shafts. This is the landscape of coal mining.”

A modern reader of newspapers and magazines will not have to search far to find contemporary eulogies for the wonderful days when coal was king, or imprecations heaped on the heads of those who engineered the collapse of the British coal industry while knowing full well that coal could be bought cheaper elsewhere.

Looking back to historical crime fiction, one of my favourite series is the Bradecote novels, set in twelfth century Worcestershire. Author Sarah Hawkswood was a distinguished historian before she began to write the novels, but it is impossible to believe that Hoskins’ wonderful account of how England was shaped was not at the back of her mind when she wrote her stories. Likewise, Chris Nickson’s novels of nineteenth century Leeds are full of the sulphurous stench of mill chimneys, the insanitary houses and the poisoned rivers that Hoskins describes in his account of the later stages of the industrial revolution.

Hoskins was lucky enough – or diligent enough – to be able to end his days in the relatively unspoilt Oxfordshire countryside, but he had a deep anger for what England had become. Below, on the left, is an angry passage from the final chapter of his book and, beside it, the last two verses of Philip Larkin’s ‘Going, going’ (1972)

The Making of the English Landscape is a magnificent tour de force; it is essential reading for those who care about England and the spirit of our ancestors who sculpted the human landscape. This edition is published by Little Toller Books and is available now.

Orland Figes (left) is an academic historian and Russia specialist, and here he brings to life one of the most peculiar and apparently pointless wars of the nineteenth century. Figes warns us at the beginning that covering the causes of the Crimean War is going to take time – and pages – so he asks us to bear with him. One of the reasons that the Russian armies of Tsar Nicholas I went to war against three Empires and a little Island state was broadly known as The Eastern Question. There have been compete books written on this alone but, put simply, it is this. The Ottoman (Turkish) Empire had reached its zenith in terms of territory by the end of the seventeenth century. By the 1850s it was in serious decline, and Western countries feared that its demise would create a political vacuum which the Russians would all too gladly fill.

Orland Figes (left) is an academic historian and Russia specialist, and here he brings to life one of the most peculiar and apparently pointless wars of the nineteenth century. Figes warns us at the beginning that covering the causes of the Crimean War is going to take time – and pages – so he asks us to bear with him. One of the reasons that the Russian armies of Tsar Nicholas I went to war against three Empires and a little Island state was broadly known as The Eastern Question. There have been compete books written on this alone but, put simply, it is this. The Ottoman (Turkish) Empire had reached its zenith in terms of territory by the end of the seventeenth century. By the 1850s it was in serious decline, and Western countries feared that its demise would create a political vacuum which the Russians would all too gladly fill.

This is what used to be called a monograph, a slim volume devoted to one particular subject. It is a million miles away from Detective Inspectors, international criminals, sleepy villages with an abundance of elderly female amateur sleuths and dark deeds on the gloomy back-streets of Victorian London. However, I do try to balance my reading between novels and non-fiction, and this book repaid my interest. The author, journalist Chris Stephen (left) has reported from nine wars for publications including the Guardian and the New York Times magazine. He is the author of Judgement Day: The Trial of Slobodan Milošević (published by Atlantic Books). Ironically, the Serbian leader avoided becoming only the third former Head of State to be found guilty of war crimes, mainly because he died of a heart attack during his trial. The first was Admiral Karl Dönitz who, for a very brief spell. was leader of Nazi Germany. The second was Charles Taylor the former Liberian leader, at whose trial Naomi Campbell made a brief but bizarre appearance as a witness. This book is part of a new series from Melville House.

This is what used to be called a monograph, a slim volume devoted to one particular subject. It is a million miles away from Detective Inspectors, international criminals, sleepy villages with an abundance of elderly female amateur sleuths and dark deeds on the gloomy back-streets of Victorian London. However, I do try to balance my reading between novels and non-fiction, and this book repaid my interest. The author, journalist Chris Stephen (left) has reported from nine wars for publications including the Guardian and the New York Times magazine. He is the author of Judgement Day: The Trial of Slobodan Milošević (published by Atlantic Books). Ironically, the Serbian leader avoided becoming only the third former Head of State to be found guilty of war crimes, mainly because he died of a heart attack during his trial. The first was Admiral Karl Dönitz who, for a very brief spell. was leader of Nazi Germany. The second was Charles Taylor the former Liberian leader, at whose trial Naomi Campbell made a brief but bizarre appearance as a witness. This book is part of a new series from Melville House.

The song, which has many more verses, was written as a sarcastic response to a statement made – allegedly by the MP Nancy Astor – criticising the 8th Army for not being part of the D Day landings in June 1944. Historian and broadcaster James Holland (left) has written an account of the Italian Campaign from the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 until the year’s end and, having read it, I can only think that the bitterness of the 8th Army men was more than justified.

The song, which has many more verses, was written as a sarcastic response to a statement made – allegedly by the MP Nancy Astor – criticising the 8th Army for not being part of the D Day landings in June 1944. Historian and broadcaster James Holland (left) has written an account of the Italian Campaign from the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 until the year’s end and, having read it, I can only think that the bitterness of the 8th Army men was more than justified.

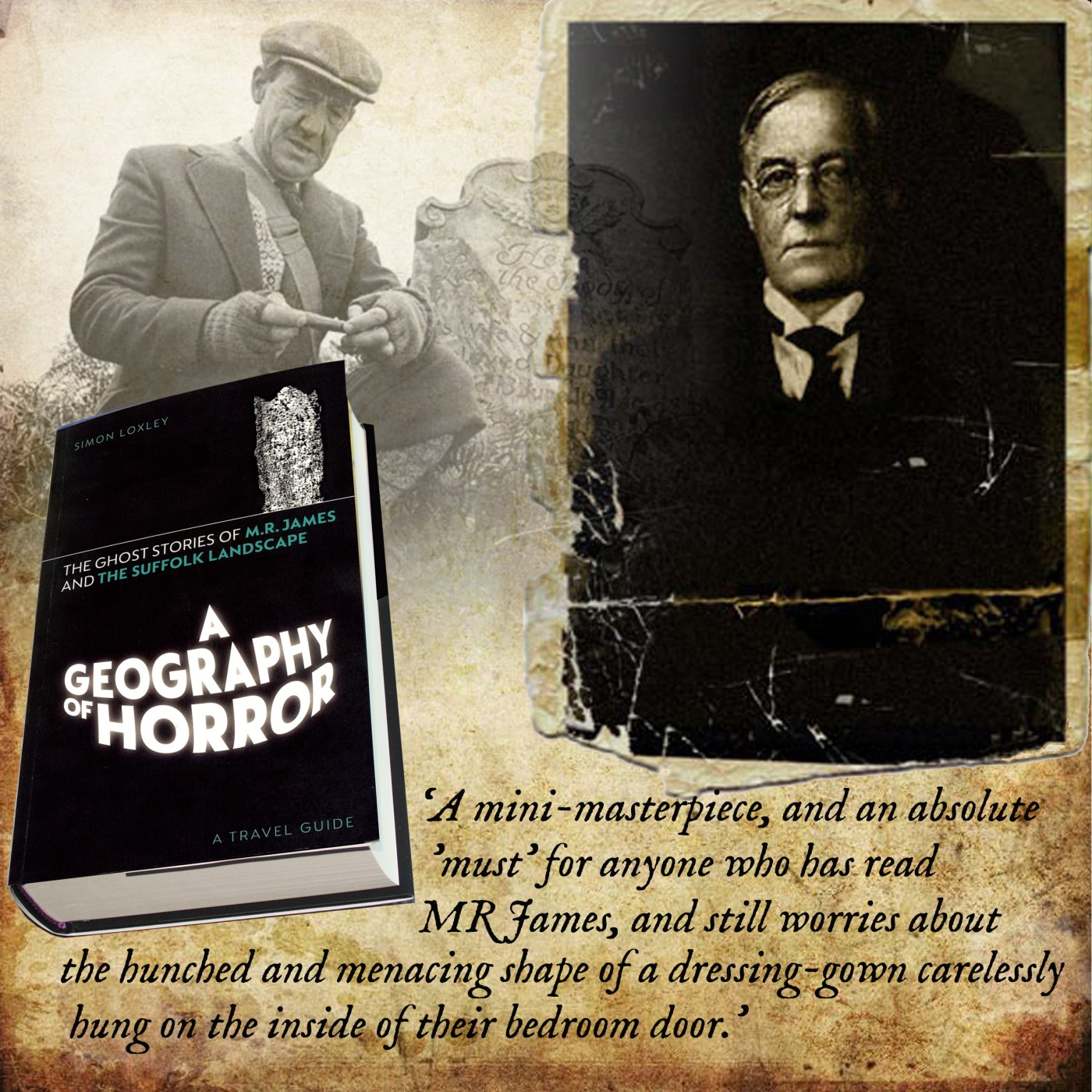

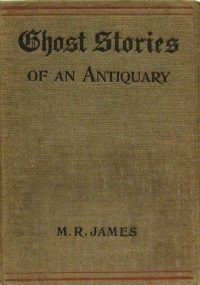

Who was the most celebrated writer of ghost stories? The genre doesn’t lend itself particularly well to longer book form, and even classics like Henry James’s The Turn of The Screw and Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black are relatively slim volumes. The master of the shorter version and, in my view, a man who unrivalled in the art of chilling the spine, was MR James. Montague Rhodes James was born in Kent in 1862, and in his main professional life he became a renowned scholar, medievalist and academic, serving as Provost of King’s College Cambridge, and Provost of Eton. His first collection of ghost stories, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, was published in 1904 and has, as far as I am aware, never been out of print.

Who was the most celebrated writer of ghost stories? The genre doesn’t lend itself particularly well to longer book form, and even classics like Henry James’s The Turn of The Screw and Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black are relatively slim volumes. The master of the shorter version and, in my view, a man who unrivalled in the art of chilling the spine, was MR James. Montague Rhodes James was born in Kent in 1862, and in his main professional life he became a renowned scholar, medievalist and academic, serving as Provost of King’s College Cambridge, and Provost of Eton. His first collection of ghost stories, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, was published in 1904 and has, as far as I am aware, never been out of print.

By the autumn of 1944, German forces had been pushed out of France and were being systematically overwhelmed by the Red Army in the east. The allies had control of the Channel coast, but the Germans had effectively wrecked the French ports. Antwerp, however, had been taken more or less intact, and when the Germans had been removed from their strong-points controlling the estuary of the River Scheldt, the Belgian port became a massive conduit for the arrival of men, machines and supplies for the Allies.

By the autumn of 1944, German forces had been pushed out of France and were being systematically overwhelmed by the Red Army in the east. The allies had control of the Channel coast, but the Germans had effectively wrecked the French ports. Antwerp, however, had been taken more or less intact, and when the Germans had been removed from their strong-points controlling the estuary of the River Scheldt, the Belgian port became a massive conduit for the arrival of men, machines and supplies for the Allies. It is one of the great paradoxes of WW2 that on the ground, at least, the Germans had the best guns, the best artillery and the best tanks. The problem was that although the formidable Panzers were easily able to overcome the relatively underpowered Sherman tanks used by the allies, the German vehicles were high maintenance and, some would say, over-engineered. The ubiquitous Shermans were rolling off the production lines in their thousands, while the formidable Tigers and Panthers – when they developed a fault – were fiendishly difficult to repair or cannibalise. Caddick-Adams (right) also reminds us how well-fed and supplied the American GIs were compared with their German foes. In one particularly eloquent passage, he tells us of the utter joy felt by a unit of Volksgrenadiers when they seized a supply of American rations. When their own kitchen unit eventually reached their position, the cooks and their containers of watery stew were given very short shrift.

It is one of the great paradoxes of WW2 that on the ground, at least, the Germans had the best guns, the best artillery and the best tanks. The problem was that although the formidable Panzers were easily able to overcome the relatively underpowered Sherman tanks used by the allies, the German vehicles were high maintenance and, some would say, over-engineered. The ubiquitous Shermans were rolling off the production lines in their thousands, while the formidable Tigers and Panthers – when they developed a fault – were fiendishly difficult to repair or cannibalise. Caddick-Adams (right) also reminds us how well-fed and supplied the American GIs were compared with their German foes. In one particularly eloquent passage, he tells us of the utter joy felt by a unit of Volksgrenadiers when they seized a supply of American rations. When their own kitchen unit eventually reached their position, the cooks and their containers of watery stew were given very short shrift.