Each decorative bar is a clickable link to

a video of the book of the day and a piece of seasonal music

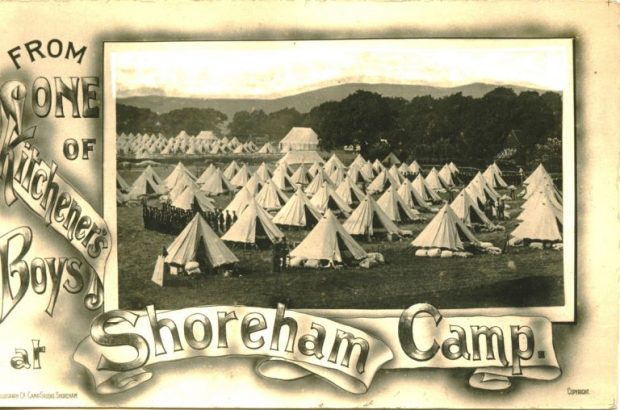

Humphrey Cobb (left) was born on 5th September 1899, in Siena, Italy. His mother was a doctor, and his father was an artist. He was sent to England for his early schooling, but then received his secondary education in America. After being expelled from high school in 1916, he decided to join the Canadian Army and was sent to Europe to fight. Remember that America did not join the war until 1917. He kept a war diary, and October 1917 has him at Shoreham Camp, in Sussex, as part of the 23rd Canadian Reserve battalion. January of 1918 has him near Hill 70, in front of Loos. He describes the death of a friend from his platoon.

Humphrey Cobb (left) was born on 5th September 1899, in Siena, Italy. His mother was a doctor, and his father was an artist. He was sent to England for his early schooling, but then received his secondary education in America. After being expelled from high school in 1916, he decided to join the Canadian Army and was sent to Europe to fight. Remember that America did not join the war until 1917. He kept a war diary, and October 1917 has him at Shoreham Camp, in Sussex, as part of the 23rd Canadian Reserve battalion. January of 1918 has him near Hill 70, in front of Loos. He describes the death of a friend from his platoon.

“What happened to Young, no-one ever knew for sure. Some thought a Fritz potato masher had landed on his respirator and that it had exploded just as he was brushing it off. Evidence: face blown in and right hand blown off. “

He saw the war out, and after being stationed in post-war Cologne for a spell, he finally arrived back in Montreal on 31st May 1919.

The years after The Great War saw Cobb involved in a variety of enterprises. He wrote Paths of Glory while working for Gallup, the advertising and polling company, and it was published in 1935 by The Viking Press. It is believed that Cobb took the core of his story from real events on the Marne front, where for Corporals from the 136th Regiment were executed after a failed attack on a German strong-point near Souain.

The years after The Great War saw Cobb involved in a variety of enterprises. He wrote Paths of Glory while working for Gallup, the advertising and polling company, and it was published in 1935 by The Viking Press. It is believed that Cobb took the core of his story from real events on the Marne front, where for Corporals from the 136th Regiment were executed after a failed attack on a German strong-point near Souain.

So how does the book stand when set alongside the film? Firstly, it has to be said that Cobb died in 1944, so any input from him was clearly impossible. Anecdote has it that Kubrick had read the book as a teenager, and had been deeply affected by it, but a chain of events led to the film screenplay differing in one essential element from the book. In the mid 1950s Kubrick was still an emerging talent as a director, and did not have the clout to persuade big studios to put up the money for an anti-war film, made in black and white. The crucial intervention came with the interest (and influence) of Kirk Douglas. The star clearly had to have a main part in the film, but who?

In the novel, Colonel Dax is a relatively peripheral figure who, reluctantly, goes along with the doomed plan to storm the German bastion which is, incidentally, called ‘The Pimple” in the novel. So, it was a bold stroke in one way for Kubrick to re-imagine Dax as the forthright and confrontational character whose personal bravery is never in doubt, and a man who just happens to have been a lawyer in civilian life. And who better to play Dax than the dimple-chinned Hollywood heart-throb Kirk Douglas?

Cobb focuses almost all of his attention in the novel on the three men who were executed, and on the various reasons why they came to be shot by their own comrades. The book has no pantomime villains, and certainly no one person who has the blood of the victims on his hands. The men die as a result of the inexorable grinding of the military machine and the numbing effect of battlefield casualty statistics. Men are reduced to numbers, compassion is subverted by casualty statistics, and procedure trumps initiative every time. As William Tecumseh Sherman may (or may not) have said, “I tell you, war is Hell!“

There are places where Kubrick and his screenwriters – Calder Willingham and Jim Thompson – did stick close to the book. The first is with the three man patrol into No Man’s Land where the cowardly and drunken Lieutenant causes the death of one of the men, thus setting up the selection of the other to be one of the judicial victims. The film plays it pretty straight, too with the events immediately prior to the execution. The character of Private Ferol is played with characteristic bravura by Timothy Carey, (right) There is one crucial difference; in the book, Ferol is chosen because he he is anti-social and widely disliked for his unpleasant behaviour, and he continues to be sarcastic and foul-mouthed right up to the point where he is strapped to the execution post. In the film, however, the enormity of his fate finally overwhelms him, and he in the unforgettable procession from the chateau to the place of execution – a chilling via dolorosa – he is reduced to a weeping, stumbling figure, clutching the arm of the Padre.

There are places where Kubrick and his screenwriters – Calder Willingham and Jim Thompson – did stick close to the book. The first is with the three man patrol into No Man’s Land where the cowardly and drunken Lieutenant causes the death of one of the men, thus setting up the selection of the other to be one of the judicial victims. The film plays it pretty straight, too with the events immediately prior to the execution. The character of Private Ferol is played with characteristic bravura by Timothy Carey, (right) There is one crucial difference; in the book, Ferol is chosen because he he is anti-social and widely disliked for his unpleasant behaviour, and he continues to be sarcastic and foul-mouthed right up to the point where he is strapped to the execution post. In the film, however, the enormity of his fate finally overwhelms him, and he in the unforgettable procession from the chateau to the place of execution – a chilling via dolorosa – he is reduced to a weeping, stumbling figure, clutching the arm of the Padre.

The final confrontation between Dax and the general doesn’t happen in the book, neither does the powerful final scene where the soldiers in the estaminet boo and mock the captured German girl who is forced to sing to them, but then they are reduced first to silence, with some in tears, and then they join in with the simple old song she is singing. Outside, Dax has just been told that the regiment has been ordered to return to the Trenches, but he walks away, leaving his men to their brief hour of peace.

It is worth repeating that Cobb’s gaze is focused on the rigid mechanism of army life. It whirrs, ticks and chimes the hours with little regard for the human lives caught up in its cogs. He shapes this in many different ways, but never better than when he describes the efforts made to make sure the execution is done ‘properly’.

“Regimental Sergeant-Major Boulanger was there, busy, competent as regimental sergeant-majors always are, in the same way that head waiters are busy, competent, or seem to be so, if they are good head waiters.”

It is to Boulanger that Cobb gives the very last action, in the last paragraph of the book, where he is given the task of administering the coup de grace to the bodies slumped against their posts.

“It must be said of Boulanger that he had some instinct for the decency of things, for, when he came to Langlois, his first thought and act was to free him from the shocking and abject pose he was in before putting an end to any life that might be clinging to him. His first shot was, therefore, one that deftly cut the rope and let the body fall away from the post to the ground. The next shot went into a brain that was already dead.”

I think that Kubrick (below) takes the gist of the novel, and shaped it to his own ends, and in doing so created a magnificent piece of cinema. His anti-war message is different from Cobb’s, but was clearly something he felt very deeply. A decade or so later he was able to return to his theme in Dr Strangelove, but this time he used satire and the comedy of the absurd to make his point.

Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 film The Paths of Glory was a limited success at the time – it just about broke even at the box office – and was initially highly controversial. It was banned in France for twenty years, and several other European countries refused to show it as a gesture of solidarity with France. It was also banned in all American military establishments. So, why the fuss?

The film, based on a book by American writer Humphrey Cobb, focuses on a section of The Western Front in 1916 held by the French. Although it is never mentioned in the film, we assume that the action takes place around Verdun, the most costly single engagement in a war that chewed up men’s lives like a meat grinder. The 701st Regiment are ordered to attack an impregnable German position known as ‘The Anthill’. General Miraud, (George Macready, above) after initially protesting to his superior that the attack would be suicidal, changes his mind after being offered promotion.

Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas, above) is the officer who will lead the attack. He is dubious about the prospects, but obeys the order. The attack is an unmitigated disaster. German shellfire halts progress in No Man’s Land, while one company is unable even to leave the trench, such is the ferocity of the bombardment. In a rage, Miraud orders his artillery to fire on his own lines in order to force the men to attack.

Miraud feels that his own honour has been impugned, and, after removing the regiment out of the line to a chateau some miles away, orders that 100 of the surviving men be arrested and charged with cowardice. The scheming General Broulard ( Adolphe Menjou, below) suggests that just three men will be enough pour encourager les autres, and Dax is forced to ask three of his company commanders to select three sacrificial victims.

Three men are chosen: Corporal Paris (Ralph Meeker) is selected because his superior officer, Lieutenant Roget, needs to silence him in case he exposes Roget’s cowardice. Private Arnaud’s name is simply drawn out of a hat, while Private Ferol (Timothy Carey) is a deeply unpleasant individual who, it seems, ‘has it coming’.

The three men are tried in a mockery of a judicial process, despite an impassioned defence by Dax, who was a lawyer in civilian life. They are sentenced to death. Dax has one last card to play. He has a written testimony that Miraud has ordered gunfire down on his own men, but it is dismissed by Broulard. The men are duly executed, with one of them, Arnaud, strapped to a stretcher after being seriously injured in a fight with his guards.

Broulard and Miraud are enjoying a leisurely breakfast in luxurious surroundings, when Dax is invited to join them. He shares his information about Miraud’s order to shell his own trenches. Miraud is told that he will face and enquiry, and then storms out voicing a sense of betrayal. Broulard congratulates Dax on a very clever plan to secure his own promotion. Dax finally loses his temper at this interpretation of his motives and rages at his superior officer.

Back at the chateau, the surviving members of the 701st Regiment are in an estaminet, drunk and reckless. The proprietor pushes a young German girl onto the makeshift stage and forces her to sing. She hesitantly sings an old song. “Der treue Husar” (The Faithful Hussar). The men’s mockery turns to empathy and then grief, as they join in with the song. Outside, Dax has just been given the order that the 701st are to return to the front line with immediate effect.

In Part two of this feature, I will explore the differences between the book and the film, and attempt to understand what Cobb and Kubrick were trying to say about this tragic episode in European history.

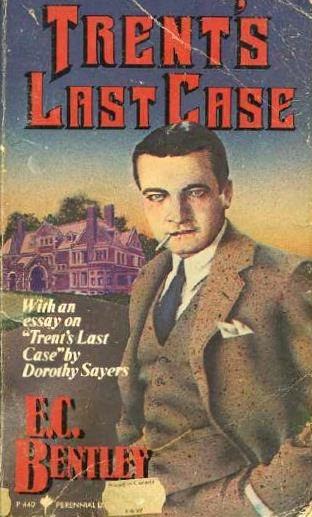

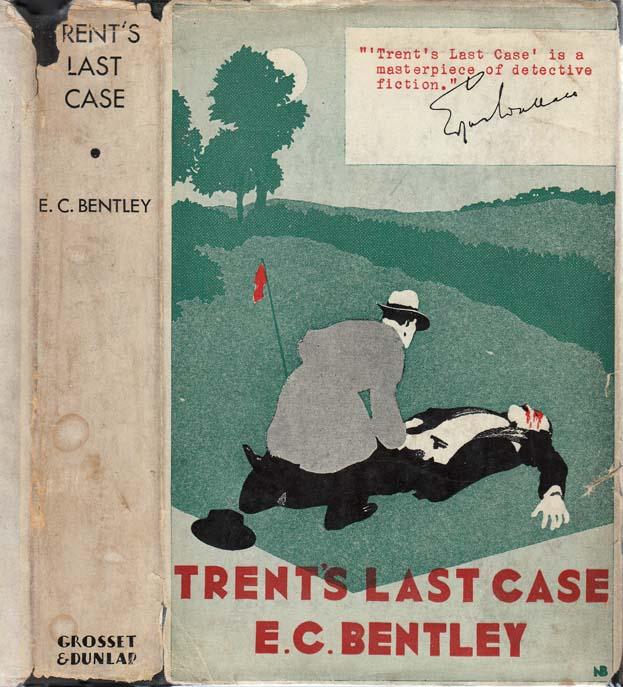

A journalist and author best remembered for inventing a form of four-line droll poetic biography that bears his middle name is an unlikely author, you might think, of one of the classic crime novels in English literature. Edmund Clerihew Bentley (1875-1956) wrote Trent’s Last Case, which was first published in 1913. It has been filmed three times, first as a silent film in 1920, again (directed by Howard Hawks) with both a silent and talkie version in 1929, and – the version I will refer to – in 1952, directed by Michael Wilcox.

The book’s title is misleading, as it was actually the first time the character of Philip Trent had appeared. The novel is regarded as a classic, and was widely admired by such fellow writers as Dorothy L Sayers, but it seems odd that Trent only featured in two more books and then only after a gap of many years.

Philip Trent is a successful painter, journalist – and amateur detective. He is summoned by his sometime employer, newspaper boss Sir James Molloy, to investigate the shooting of American businessman Sigsbee Manderson, at his country house in the south west of England. Manderson was a ruthless plutocrat who had made many enemies in his pursuit of riches, but even discounting those, the house itself offers a hatful of suspects, including the butler, Mabel (Manderson’s wife) and two male secretaries who dealt, respectively, with his social and business affairs.

Philip Trent is a successful painter, journalist – and amateur detective. He is summoned by his sometime employer, newspaper boss Sir James Molloy, to investigate the shooting of American businessman Sigsbee Manderson, at his country house in the south west of England. Manderson was a ruthless plutocrat who had made many enemies in his pursuit of riches, but even discounting those, the house itself offers a hatful of suspects, including the butler, Mabel (Manderson’s wife) and two male secretaries who dealt, respectively, with his social and business affairs.

Check the date of publication. 1913. I am not sure if The Moonstone (Wilkie Collins, 1868) is exactly a Country House Mystery, but I can’t think of anything else that comes before Trent’s Last Case that includes elements we have come to regard as staples of the genre – the grand house, the butler, the maids, the examination of movements and motives among the house residents. Remember that it was to be another seven years before Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles, and the subsequent flowering of such companion talents as Dorothy L Sayers and Margery Allingham. To put Bentley’s novel into sharper context, bear in mind that His Last Bow and The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes were still be published, in 1917 and 1927 respectively.

So, to the book, the film and how they relate to each other. Readers of the book may have to keep pinching themselves so that they remember this takes place in 1913. We are still, despite ‘Bertie’ dying three years earlier, in Edwardian England. The ravages of The Great War were still to come. The film sets the action pretty much contemporary with the production, that is to say, post-war England. In the novel, we only see Sigsbee Manderson through Trent’s examination of his personal possessions, and the testimonies of the other inhabitants of White Gables. The box office potential of having Orson Welles play the odious businessman, however, was obviously too much for the producers to resist, and the big man (right, complete with strange prosthetic nose) puts in a characteristically bravura performance in a flashback cameo towards the end of the film.

So, to the book, the film and how they relate to each other. Readers of the book may have to keep pinching themselves so that they remember this takes place in 1913. We are still, despite ‘Bertie’ dying three years earlier, in Edwardian England. The ravages of The Great War were still to come. The film sets the action pretty much contemporary with the production, that is to say, post-war England. In the novel, we only see Sigsbee Manderson through Trent’s examination of his personal possessions, and the testimonies of the other inhabitants of White Gables. The box office potential of having Orson Welles play the odious businessman, however, was obviously too much for the producers to resist, and the big man (right, complete with strange prosthetic nose) puts in a characteristically bravura performance in a flashback cameo towards the end of the film.

The film is workmanlike and sticks fairly closely to the narrative of the book, including the eventual solution to Manderson’s death. Although the film ends with Margaret Lockwood (Mabel Manderson) and Michael Wilding (Trent) having a fairly chaste snog, the screenplay doesn’t come close to the intensity of Trent’s infatuation – although he behaves like a perfect gentleman – with Mabel. The film Trent is matinee-idol suave – as indeed Wilding was at this stage of his career – but is much tougher than Bentley’s Trent. Not that the Trent in the book is flabby. In between the initial investigation and the denouement, Trent goes away and acts as a war correspondent in a blood-soaked civil war somewhere in Central Europe. It is more that the literary detective is much more loquacious and passionate, and is given to quoting Shelley and Swinburne.

Again, I say remember the date. 1913. Some critics have even suggested that Bentley had his tongue discreetly in his cheek when he wrote the novel, but by the time the film was made, almost forty years and two world wars later, huge swathes of the novel would never have got into the script, and the social and emotional nuances would have bemused 1950s cinema audiences.

To sum up, Trent investigates, gets it almost right, falls in love with the widow, sets out his solution on paper and then, unwilling to disclose his solution for fear of the hurt it will cause, goes off to a frightful war to seek oblivion. When he returns, he presents his version of events, only to find he was correct in all but the crucial detail of whose finger was on the trigger when Manderson was shot. The book is spirited, and full of entertainment as Bentley harmlessly shows off how clever he is. The film does an adequate job and is worth watching, if only for Orson Welles hamming it up for dear life, and a brief appearance by Kenneth Williams (even then as camp as a row of tents) as the gardener (below) who discovers the body.

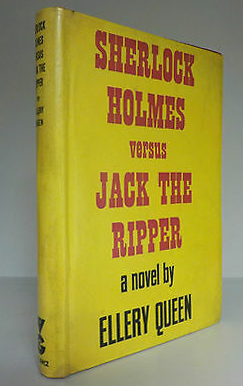

The first, Sherlock Holmes versus Jack the Ripper, by ‘Ellery Queen’ was published in 1967. This was a novelisation of the screenplay of ‘A Study in Terror’, co-produced by Sir Nigel Films Limited, a company formed by the Estate to exploit Conan Doyle’s works on screen. The book added a framing story wherein Ellery Queen reads a manuscript (written by Dr Watson) which sets out the action shown in the film. Queen then applies his own detective skills to ascertain whether Holmes correctly identified the Ripper. The Ripper section of the book was the work of pulp writer Paul Fairman, and the Ellery Queen part by presumably ‘Ellery Queen’ himself. An early line of Dr Watson’s narrative reads:

The first, Sherlock Holmes versus Jack the Ripper, by ‘Ellery Queen’ was published in 1967. This was a novelisation of the screenplay of ‘A Study in Terror’, co-produced by Sir Nigel Films Limited, a company formed by the Estate to exploit Conan Doyle’s works on screen. The book added a framing story wherein Ellery Queen reads a manuscript (written by Dr Watson) which sets out the action shown in the film. Queen then applies his own detective skills to ascertain whether Holmes correctly identified the Ripper. The Ripper section of the book was the work of pulp writer Paul Fairman, and the Ellery Queen part by presumably ‘Ellery Queen’ himself. An early line of Dr Watson’s narrative reads:

“It was a crisp morning in the fall of the year 1888″:

A warning for American writers attempting this sort of thing.

“The story is couched as an alternative explanation for the period between Holmes’s supposed death at the hands of Moriarty (‘The Final Problem’) and his resurrection (‘The Empty House’). The hiatus which began with Holmes drying out extends into a case involving a pasha, a baron and a red headed temptress, during which Holmes instructs Freud in the mechanics of detection and gives some advice about the meaning of dreams.”

“The story is couched as an alternative explanation for the period between Holmes’s supposed death at the hands of Moriarty (‘The Final Problem’) and his resurrection (‘The Empty House’). The hiatus which began with Holmes drying out extends into a case involving a pasha, a baron and a red headed temptress, during which Holmes instructs Freud in the mechanics of detection and gives some advice about the meaning of dreams.”

The final five in my personal list of the best twenty five British TV detectives all have one thing in common, and it is that they were dominated by bravura performances from the lead characters. Of course the other twenty actors, Helen Mirren, George Baker, Rupert Davies et al were good – maybe even excellent – but these five were in a different league.

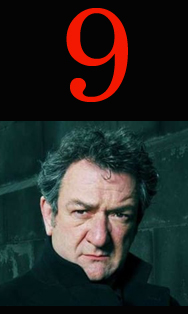

A big man, playing an outsize role – that was Robbie Coltrane’s portrayal of Eddie ‘Fitz’ Fitzgerald, the criminal psychologist whose astonishing powers of analysis gave him the nickname Cracker. Fitz smoked too much, drank too much, gambled way, way too much; in so many ways, especially for his long suffering wife (Barbara Flynn) and the police officers who employed him (Christopher Eccleston and Geraldine Somerville), the overweight and overbearing Scotsman simply was too much. Cracker was no Sunday evening show to snuggle up with; it was brutal, bleak and frequently uncomfortable viewing, featuring some genuinely disturbed and disturbing criminals, perhaps none more so than the truly frightful Albie Kinsella (Robert Carlyle). There were three series between 1993 and 1995, with two specials in 1996 and 2006. The series was set in Manchester, but the initial writing by Jimmy McGovern, and the inclusion of such actors as Ricky Tomlinson somehow gave the shows a Liverpool mood. This was never more evident than the episodes featuring the murderous Kinsella, who claimed that much of his rage was fuelled by the injustices which followed the Hillsborough disaster. There were moments of bitter humour, particularly in the exchanges between Fitz and some of the more unreconstructed coppers:

Jimmy Beck: Shall I tell you why I can’t stand lesbians?

Eddie “Fitz” Fitzgerald: Please.

Jimmy Beck: Queers are OK, as long as I don’t turn my back on you, you’re OK. Two queers doing it, that’s two women going spare. But two lesbians doing it, that’s two men going short.

Eddie “Fitz” Fitzgerald: You can tell he reads The Guardian can’t you?

Fictional detectives can be many things. Some are brutal, some are happily married with stable families, many are embittered, doing a difficult job despite personal heartbreak Few, however, have been poets. One such was Adam Dalgliesh. His creator, PD James not only made him a published and widely respected poet, but also gave him the highest police rank of all my chosen coppers – by the end of the novels he had risen to the rank of Commander in London’s Metropolitan Police. Of the fourteen Dalgliesh novels ten were filmed for ITV, each starring Roy Marsden ans the cerebral detective. Two other novels, Death In Holy Orders and The Murder Room were commissioned by the BBC with Martin Shaw playing Dalgliesh. Marsden was perfect as the slightly old fashioned gentleman detective who, rather like Lord Peter Wimsey, was of independent means, thanks to his wealthy family. Tall, always beautifully dressed and with a studied elegance almost out of keeping with the often brutal deaths he had to investigate, he was a compelling screen presence. Dalgliesh does have romantic relationships with women, but they are usually on his own terms, and characterised by his reluctance to commit himself fully. Althouh the TV adapatations were not always resolutely faithful to the novels, they still retained the original elegance and sense that we were engaging with something rather more profound that a crime fiction potboiler. The series began with Death Of An Expert Witness in 1983 and concluded with A Certain Justice in 1998.

Another suave and quietly spoken detective graced our screens across eight series between 2002 and 2015. Foyle’s War had the benefit of being almost exclusively written by its creator Anthony Horowitz, and the continuity of tone and atmosphere was almost tangible. Michael Kitchen played Detective Chief Superintendent Christopher Foyle, a policeman operating on the south coast of England during WWII. He is a Great War veteran, a widower, and has a son serving as a pilot in the RAF. Wartime England was not a tranquil oasis of plucky folk all pulling together, keeping calm and ‘carrying on’. Regular criminals rejoiced in the police losing manpower to the armed services and relished the blackout regulations. A new breed of villain emerged – men and women who sought to exploit the stringent austerity regulations imposed by the wartime government. Sometimes Foyle finds these are relatively petty spivs, ‘Wholesale Suppliers’ like Private Walker of Dad’s Army, but on other occasions they are much higher up the food chain – factory bosses or high ranked civil servants. With the rather dour and troubled Sergeant Milner (Anthony Howell) at his side, and ferried everywhere by Samantha Stewart (Honeysuckle Weeks) with her ‘jolly hockey sticks’ charm, Foyle is frequently underestimated by the criminals he pursues, and often viwed with suspicion by his superiors, who suspect him of being a member of ‘the awkward squad’. The final two series saw the end of the war, and Foyle working for MI5, but Kitchen’s impeccable and understated screen presence never faltered. He had a superbly quizzical facial tic, something like a sideways grimace; when he produced that, we always knew that he knew he was being told lies, and it was only a matter of time before he upset the official apple-cart, and had the real crooks under lock and key.

I haven’t made it the basis of my long-deferred PhD thesis, so there is no peer-reviewed data, but there can be no fictional detective with as many stage and screen – and radio – impersonations as Sherlock Holmes. In my lifetime I can name Rathbone, Cushing, Wilmer, Hobbs, Merrison, Gielgud, Plummer, McKellen – and that’s without mentioning the times he was played for laughs, or modernised beyond the pale. Each of these gentlemen brought something different to the role, but for me the late Jeremy Brett will never be bettered. His untimely death in 1994 ended a series which began a decade earlier, but with forty two canonical stories completed his legacy is beyong compare. Why was he so good? Where to start! Purely physically, Brett had the dry and sometimes sardonic voice, the crisp and mannered delivery and the piercing stare. The raised eyebrow, the steepled fingertips and the eyes half-closed in contemplation were, of course, totally studied and practiced, but how effective they were. Brett was rarely called upon to demonstrate Holme’s skill as a pugilist, but nonetheless his movements gave the impression of a man of intense vitality and energy stored like a coiled spring. The wonderful production values did the series no harm at all, neither did the fact that several ‘A’ list actors graced the show with their presence, in particular Colin Jeavons as Lestrade, Eric Porter as Moriarty and Charles Gray as brother Mycroft. Watson? I think that such was Brett’s dominance that it didn’t matter too much who played Watson, and although David Burke and Edward Hardwicke put in perfectly adequate performances, neither would come to be mentioned in the same sense that we look back on Rathbone and Bruce, or Cushing and Stock. Jeremy Brett’s personal life was complex in the extreme, and his deteriorating health became a great challenge as the series reached its premature end. Perhaps it was this personal distress which made viewers of a different and more complex Holmes – a troubled man whose inner conflicts were hidden beneath the icy exterior.

And so to number one, the nonpareil. Some of my choices – or their positions in the ‘chart’ – will not have met with universal agreement, but that is fine. This, and any other ‘best of’ feature is never going to be based on irrefutable data, or numbers, or scientific evaluation. It’s all about emotional impact, memory, and whichever heart-strings are tugged. I was pointed in the direction of Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse novels when I was an earnest young teacher at a posh preparatory school back in the mid 1970s. Last Bus To Woodstock was still relatively hot off the press and – thank God for public libraries – I followed the progress of the quirky Oxford copper into the 1980s. When TV finally caught up with the reading public, and commissioned The Dead of Jericho, broadcast in January 1987, it was a revelation. In my mind’s eye I saw Morse as being a rather younger version of his creator, but here was a revelation. John Thaw was already a TV star, but gone was the brash violence, snarling cockney slang and horribly flared trousers of The Sweeney. Instead, we were shown a private, circumspect and conflicted man. Sometimes uncomfortable in company, but bolstered professionally – and sometimes personally – by the down-to-earth solidity of Sergeant Robbie Lewis, Morse was a genuine one-off. Apparently from a humble background, his intellect encompassed rattling through The Times crossword, a love of the divine music of Mozart and Wagner and a ‘cleverness’ which made him a constant irritant to Chief Superintendent Strange, memorably played by James Grout. This will be controversial, but I contend that John Thaw took the character of Colin Dexter’s Morse and shifted it from being simply memorable, to being immortal. A screen version better than the original book? I can already hear cries of ‘heretic!’, ‘burn him!’. Sorry, but I will approach my funeral pyre with my head held high. Thaw’s Morse will live for ever in my memory, whether cruising around the streets of Oxford in his blissful red Jaguar, or hunkered down over a decent pint trying to explain something to the slightly dim Lewis (beautifully imagined by Kevin Whately) or – most memorably, alone in his house with a glass of single malt in his hand, pondering the imponderable with, perhaps, Siegfried’s funeral music from Götterdämmerung playing in the background. Nothing will ever cap this for me and, for what it’s worth I can still hum every bar of Barrington Pheloung’s wonderful theme music to what was the best detective series ever broadcast on British television.

You can never have too many Detective Inspectors, can you? Well, I’m afraid you can in crime novels and TV adaptations, and a DI’s annual convention would need to book a very large hotel and conference centre. My ‘best of’ list only has twenty five names on it, and so some famous names had to accept early retirement. Apologies to fans of Banks, Barnaby, Lynley, Thorne and Wycliffe (OK, he was a Superintendent) – but there are always the box sets to enjoy. My next selection of TV series to remember starts with the most elderly, date-wise.

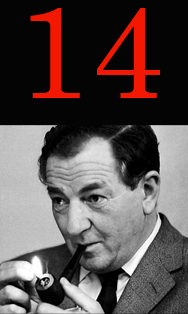

In more recent times Michael Gambon and Rowan Atkinson have made decent stabs at characterising Jules Maigret, Simenon’s Parisian detective, but the Rupert Davies version is the one for me. The grainy black and white presentation would now be considered as un hommage to moody 1940s crime films but, more prosaically, it was all our TV sets could cope with back in the day. Maybe it was the iconic title sequence – the match being struck to light the ever-present pipe, with Ron Grainer’s haunting accordion soundtrack. Maybe it was a teenage Brit’s first glimpse of those beautiful rakish Citroen cars. Maybe it was Ewen Solon’s brilliant turn as Maigret’s sidekick Lucas, but whatever the reason, this was TV gold. (1960 – 1963)

In more recent times Michael Gambon and Rowan Atkinson have made decent stabs at characterising Jules Maigret, Simenon’s Parisian detective, but the Rupert Davies version is the one for me. The grainy black and white presentation would now be considered as un hommage to moody 1940s crime films but, more prosaically, it was all our TV sets could cope with back in the day. Maybe it was the iconic title sequence – the match being struck to light the ever-present pipe, with Ron Grainer’s haunting accordion soundtrack. Maybe it was a teenage Brit’s first glimpse of those beautiful rakish Citroen cars. Maybe it was Ewen Solon’s brilliant turn as Maigret’s sidekick Lucas, but whatever the reason, this was TV gold. (1960 – 1963)

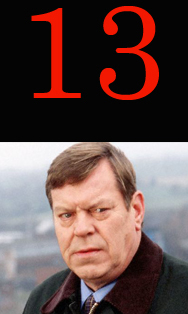

The twenty four novels by Reginald Hill featuring the overweight and irascible Yorkshire copper Andy Dalziel had the fat man firmly centre stage, but when he was brought to the small screen, his rather more politically correct Sergeant, Peter Pascoe shares the billing. There were eleven series between 1996 and 2007 and Warren Clarke played Dalziel throughout, Clarke was certainly blunt and low on corporate charm, but he was never quite as gross as the written character. The series had tremendous writers, including Malcolm Bradbury and Alan Plater in the early days. Pascoe’s lecturer wife Ellie provided what we would now call a ‘woke’ response to Dalziel’s ‘gammon’ but by series six she and Peter they had gone their separate ways, his disdain for wrong-doers clashing once to often with her metropolitan liberal values.

The twenty four novels by Reginald Hill featuring the overweight and irascible Yorkshire copper Andy Dalziel had the fat man firmly centre stage, but when he was brought to the small screen, his rather more politically correct Sergeant, Peter Pascoe shares the billing. There were eleven series between 1996 and 2007 and Warren Clarke played Dalziel throughout, Clarke was certainly blunt and low on corporate charm, but he was never quite as gross as the written character. The series had tremendous writers, including Malcolm Bradbury and Alan Plater in the early days. Pascoe’s lecturer wife Ellie provided what we would now call a ‘woke’ response to Dalziel’s ‘gammon’ but by series six she and Peter they had gone their separate ways, his disdain for wrong-doers clashing once to often with her metropolitan liberal values.

Another Sunday evening comfort blanket was provided by the long running – fifteen series between 1992 and 2010 – A Touch of Frost. Here was another policeman who, like Andy Dalziel, trod on toes and infuriated his superiors. William ‘Jack’ Frost, however, was less abrasive and with a more melancholy approach to life’s vicissitudes. Sir David Jason was a National Treasure before he took on the mantle of Frost, and his wonderful combination of jaunty disregard for protocol and inner sadness was masterful. RD Wingfield only wrote six Frost novels, and so the TV series outdistanced the books by many a mile. One of the delights of the show was the constant sparring between Frost and his starchy boss Superintendent Mullett, beautifully played by Bruce Alexander.

Another Sunday evening comfort blanket was provided by the long running – fifteen series between 1992 and 2010 – A Touch of Frost. Here was another policeman who, like Andy Dalziel, trod on toes and infuriated his superiors. William ‘Jack’ Frost, however, was less abrasive and with a more melancholy approach to life’s vicissitudes. Sir David Jason was a National Treasure before he took on the mantle of Frost, and his wonderful combination of jaunty disregard for protocol and inner sadness was masterful. RD Wingfield only wrote six Frost novels, and so the TV series outdistanced the books by many a mile. One of the delights of the show was the constant sparring between Frost and his starchy boss Superintendent Mullett, beautifully played by Bruce Alexander.

The Hazell books were an oddity. They were written by jobbing Scots journalist Gordon Williams, with the unlikely assistance of football’s wide-boy, Terry ‘El Tel’ Venables. Under the pseudonym PB Yuill, they were tight and well-written tales of a London wide boy making a living as a private detective. On screen, Nicholas Ball – all bouffant hair, snappy clothes and attitude – was simply perfect. As a general rule, British PI dramas are never going to compete with their USA counterparts in the violent, mean and noirish stakes, but the Hazell shows tapped into a ‘cheeky cockney’ chic which could only have worked in a London setting. Stuart Radmore, who sometimes writes for Fully Booked, is an erudite and voracious collector of rare crime novels, but one of his most prized possessions is a glossy covered Hazell annual, with graphic novel versions of stories, with helpful translations of cockney rhyming slang, The trendy locations combined with solid support from actors such as Roddy MacMillan made this relatively short lived series one to be remembered with affection. (1978 – 1979) For Stuart’s take on the Hazell books, click this link.

The Hazell books were an oddity. They were written by jobbing Scots journalist Gordon Williams, with the unlikely assistance of football’s wide-boy, Terry ‘El Tel’ Venables. Under the pseudonym PB Yuill, they were tight and well-written tales of a London wide boy making a living as a private detective. On screen, Nicholas Ball – all bouffant hair, snappy clothes and attitude – was simply perfect. As a general rule, British PI dramas are never going to compete with their USA counterparts in the violent, mean and noirish stakes, but the Hazell shows tapped into a ‘cheeky cockney’ chic which could only have worked in a London setting. Stuart Radmore, who sometimes writes for Fully Booked, is an erudite and voracious collector of rare crime novels, but one of his most prized possessions is a glossy covered Hazell annual, with graphic novel versions of stories, with helpful translations of cockney rhyming slang, The trendy locations combined with solid support from actors such as Roddy MacMillan made this relatively short lived series one to be remembered with affection. (1978 – 1979) For Stuart’s take on the Hazell books, click this link.

Fictional enquiry agents are supposed to wear old raincoats and no-one wore one quite like Frank Marker in Public Eye. World-weary, downtrodden, shabby, tired and frequently unsuccessful, Marker was played brilliantly by Alfred Burke. Public Eye was intended as a counterweight to flashy, urbane detective series headed up by some lantern-jawed alpha male rodding around in a flashy car. First written by Roger Marshall and Anthony Marriot, the show aired on on ABC television in 1965, in glorious black and white. The last episode of the final series, the seventh, was broadcast in April 1975 and was in colour. The glossier format had no effect on Marker’s misfortunes, and by then he had been in prison, as well as changing locations from London to Brighton and then to Eton. Public Eye could only have succeeded in Britain. Certainly Colombo was dishevelled and apparently scatterbrained, but he always had the last laugh. Not so Frank Marker, who frequently ended up with the proverbial egg on his face. The British – English, even – predilection for the enigmatic and downbeat was echoed in the intriguing titles of many of the episodes. “Well—There Was This Girl, You See…”, “Cross That Palm When We Come To It” and “Nobody Kills Santa Claus” were typical. Alfred Burke was also a theatrical actor of great distinction. He died in 2011, a few days short of his 93rd birthday.

Fictional enquiry agents are supposed to wear old raincoats and no-one wore one quite like Frank Marker in Public Eye. World-weary, downtrodden, shabby, tired and frequently unsuccessful, Marker was played brilliantly by Alfred Burke. Public Eye was intended as a counterweight to flashy, urbane detective series headed up by some lantern-jawed alpha male rodding around in a flashy car. First written by Roger Marshall and Anthony Marriot, the show aired on on ABC television in 1965, in glorious black and white. The last episode of the final series, the seventh, was broadcast in April 1975 and was in colour. The glossier format had no effect on Marker’s misfortunes, and by then he had been in prison, as well as changing locations from London to Brighton and then to Eton. Public Eye could only have succeeded in Britain. Certainly Colombo was dishevelled and apparently scatterbrained, but he always had the last laugh. Not so Frank Marker, who frequently ended up with the proverbial egg on his face. The British – English, even – predilection for the enigmatic and downbeat was echoed in the intriguing titles of many of the episodes. “Well—There Was This Girl, You See…”, “Cross That Palm When We Come To It” and “Nobody Kills Santa Claus” were typical. Alfred Burke was also a theatrical actor of great distinction. He died in 2011, a few days short of his 93rd birthday.

Ian Rankin’s saturnine Edinburgh copper John Rebus, over the course of twenty two best-selling novels, has become the doyen of gritty Scottish coppers – often imitated but never bettered. With so many examples of voracious demand for TV productions outstripping the original novels by other authors, it is worth noting that there were just fourteen TV episodes between 2000 and 2007, and there was a change of Rebus in there, too. John Hannah was our man in the first series, but Ken Stott took on the role for the other three series. Opinion is divided on their respective merits. Some said that Hannah did not match the physicality of the detective, but others thought his version had more psychological depth than the later episodes. The crucial support characters of DS Siobhan Clarke and DCI Gill Templer also changed actors across the series. Given that Rebus has an army background where he even graduated to the elite SAS, the abrasive Ken Stott has my vote, for what it’s worth.

Ian Rankin’s saturnine Edinburgh copper John Rebus, over the course of twenty two best-selling novels, has become the doyen of gritty Scottish coppers – often imitated but never bettered. With so many examples of voracious demand for TV productions outstripping the original novels by other authors, it is worth noting that there were just fourteen TV episodes between 2000 and 2007, and there was a change of Rebus in there, too. John Hannah was our man in the first series, but Ken Stott took on the role for the other three series. Opinion is divided on their respective merits. Some said that Hannah did not match the physicality of the detective, but others thought his version had more psychological depth than the later episodes. The crucial support characters of DS Siobhan Clarke and DCI Gill Templer also changed actors across the series. Given that Rebus has an army background where he even graduated to the elite SAS, the abrasive Ken Stott has my vote, for what it’s worth.

Idris Elba, the star of Luther, cut his crime drama teeth in the American series The Wire, but when Luther first appeared in 2010, it was obvious that Elba had made the big time as the conflicted, violent but analytical London DCI. The plots were dark and full of menace, and the writers struck gold when they introduced the character of Alice Morgan, a psychopathic killer. After Luther fails in his attempt to to bring her to justice, it becomes clear that there is more unites Luther and Morgan than divides them, thus raising the uncomfortable thought that there is a fine line between ruthless policing and getting away with serious crime. Series Five of the drama in 2019 was, effectively a movie length production, split into four episodes broadcast on consecutive nights. Luther’s chaotic personal life comes back not only to haunt him, but it seems to weave a fatal web around everyone – colleague or criminal – who becomes involved with him. The violence was as graphic as anything seen on British TV for some time, and the story ended by posing more questions than it answered about the future of DCI John Luther.

Idris Elba, the star of Luther, cut his crime drama teeth in the American series The Wire, but when Luther first appeared in 2010, it was obvious that Elba had made the big time as the conflicted, violent but analytical London DCI. The plots were dark and full of menace, and the writers struck gold when they introduced the character of Alice Morgan, a psychopathic killer. After Luther fails in his attempt to to bring her to justice, it becomes clear that there is more unites Luther and Morgan than divides them, thus raising the uncomfortable thought that there is a fine line between ruthless policing and getting away with serious crime. Series Five of the drama in 2019 was, effectively a movie length production, split into four episodes broadcast on consecutive nights. Luther’s chaotic personal life comes back not only to haunt him, but it seems to weave a fatal web around everyone – colleague or criminal – who becomes involved with him. The violence was as graphic as anything seen on British TV for some time, and the story ended by posing more questions than it answered about the future of DCI John Luther.

While Ruth Rendell was a master at writing stand-alone psychological thrillers, her creation of Chief Inspector Reg Wexford will be her abiding achievement in the eyes of many readers and viewers of TV crime dramas. He first appeared an improbable 56 years ago in From Doon With Death and his last appearance in print was in No Man’s Nightingale (2013) just two years before Rendell’s death. It wasn’t until 1987, however, that he first appeared on TV screens.There were twelve series in all, lasting until 2000. The first title was The Ruth Rendell Mysteries, but as Wexford became something of a fixture, the name changed to The Inspector Wexford Mysteries. Wexford was, however, to play an increasingly marginal role in the later broadcasts, as the writers played Lego with various fragments and short stories from the author. George Baker was Reg Wexford and those whose only memory of him is as the avuncular, rather old-fashioned family man – with an endearing Hampshire burr – may be surprised to learn that Baker had been a dashing male lead in his day, so much so that he was Ian Fleming’s first choice as a screen James Bond. As always in great TV shows, there was stellar teamwork from such supporting actors as Christopher Ravenscroft as the waspish and rather uptight Mike Burden, and Louie Ramsay as Dora Wexford, his long suffering wife.

While Ruth Rendell was a master at writing stand-alone psychological thrillers, her creation of Chief Inspector Reg Wexford will be her abiding achievement in the eyes of many readers and viewers of TV crime dramas. He first appeared an improbable 56 years ago in From Doon With Death and his last appearance in print was in No Man’s Nightingale (2013) just two years before Rendell’s death. It wasn’t until 1987, however, that he first appeared on TV screens.There were twelve series in all, lasting until 2000. The first title was The Ruth Rendell Mysteries, but as Wexford became something of a fixture, the name changed to The Inspector Wexford Mysteries. Wexford was, however, to play an increasingly marginal role in the later broadcasts, as the writers played Lego with various fragments and short stories from the author. George Baker was Reg Wexford and those whose only memory of him is as the avuncular, rather old-fashioned family man – with an endearing Hampshire burr – may be surprised to learn that Baker had been a dashing male lead in his day, so much so that he was Ian Fleming’s first choice as a screen James Bond. As always in great TV shows, there was stellar teamwork from such supporting actors as Christopher Ravenscroft as the waspish and rather uptight Mike Burden, and Louie Ramsay as Dora Wexford, his long suffering wife.

Prime Suspect broke new TV ground in many ways. It was certainly the first notable crime drama centred on a female character, and it also created an appetite among TV viewers for movie length dramas to be broadcast on consecutive nights, such as a long Bank Holiday weekend. By the time the series began in 1991, Helen Mirren was already an established box office star, having gone from Shakespeare to Broadway and conquering all before her. The only time I ever saw her live was at the RSC in 1970, when she was a mesmerising Elizabeth Woodville being brutally wooed by Norman Rodway’s Richard III. Mirren brought both glamour and determination to the role of DCI (to become Detective Superintendent) Jane Tennison. There were seven series between 1991 and 2006 and for the first five at least the viewing figures were in the 14 million range. So did people just tune in to see a genuine ‘ball-breaker’ in action? Certainly anti-female bias in the police force was part of the deal, but a brilliant initial concept by writer Lynda LaPlante, superb supporting turns from actors like Tom Bell, Tom Wilkinson, Zoe Wanamaker, Ralph Fiennes and Mark Strong and, of course, Mirren’s own nuanced and steely brilliance meant that the show could hardly go wrong.

Prime Suspect broke new TV ground in many ways. It was certainly the first notable crime drama centred on a female character, and it also created an appetite among TV viewers for movie length dramas to be broadcast on consecutive nights, such as a long Bank Holiday weekend. By the time the series began in 1991, Helen Mirren was already an established box office star, having gone from Shakespeare to Broadway and conquering all before her. The only time I ever saw her live was at the RSC in 1970, when she was a mesmerising Elizabeth Woodville being brutally wooed by Norman Rodway’s Richard III. Mirren brought both glamour and determination to the role of DCI (to become Detective Superintendent) Jane Tennison. There were seven series between 1991 and 2006 and for the first five at least the viewing figures were in the 14 million range. So did people just tune in to see a genuine ‘ball-breaker’ in action? Certainly anti-female bias in the police force was part of the deal, but a brilliant initial concept by writer Lynda LaPlante, superb supporting turns from actors like Tom Bell, Tom Wilkinson, Zoe Wanamaker, Ralph Fiennes and Mark Strong and, of course, Mirren’s own nuanced and steely brilliance meant that the show could hardly go wrong.

While nothing beats a good book, detectives on TV come a close second. At the age of 72 I have seen a fair few of these small screen sleuths, and I’ve made a purely subjective list of the best twenty five. My shortlist ran to well over sixty, and if some who didn’t make the cut are your personal favourites, then please accept my commiserations. It’s also worth saying that of my twenty five, the majority are adaptations of books.

First, my criteria for inclusion. My choices are all British productions featuring British actors and, with two exceptions, mostly British settings. I’ve excluded ensemble police procedurals such as Z Cars, The Bill and Waking The Dead. I have, regretfully, left out my all time classic TV crime drama Callan, because dear old David wasn’t so much a detective as an enforcer or a cleaner-up of the messes created by his shadowy employers. Each of my choices has a readily identifiable – and sometimes eponymous – leading character, to the extent that were the man or woman on the proverbial omnibus shown a photograph of, for example, George Baker, they would say, “Ah yes – Wexford!” Please feel free to vent your outrage at omissions or inclusions via the usual social media networks, but here goes:

Victorian coppers were not new to TV when this Sergeant Cribb, based on the excellent Peter Lovesey novels, first aired. There had already been several attempts at the Holmes canon, and way back in 1963 John Barrie starred as Sergeant Cork. Although a serial, rather than a series, the 1959 version of The Moonstone featured the great Patrick Cargill as Sergeant Cuff, possibly the first fictional detective. Where Sergeant Cribb came to life was through the superbly dry and acerbic characterisation of Alan Dobie, aided and abetted by the ever-dependable William Simons. Neither did it hurt that most of the episodes were written by Peter Lovesey himself. (1980 – 1981)

Victorian coppers were not new to TV when this Sergeant Cribb, based on the excellent Peter Lovesey novels, first aired. There had already been several attempts at the Holmes canon, and way back in 1963 John Barrie starred as Sergeant Cork. Although a serial, rather than a series, the 1959 version of The Moonstone featured the great Patrick Cargill as Sergeant Cuff, possibly the first fictional detective. Where Sergeant Cribb came to life was through the superbly dry and acerbic characterisation of Alan Dobie, aided and abetted by the ever-dependable William Simons. Neither did it hurt that most of the episodes were written by Peter Lovesey himself. (1980 – 1981)

I am sure the loss is all mine, but of the Golden Age female crime writers I have found Agatha Christie the least interesting, despite her ingenious plotting and ability to create atmosphere. Mea Culpa, I suppose, but it would be reckless not to include Miss Marple in this list. Geraldine McEwan and Julia McKenzie have their admirers, but Joan Hickson is, surely, the Miss Marple? Her series (1984 – 1992) was certainly the most canonical and, if the anecdote is to be believed, Agatha Christie herself once sent a note to the younger Hickson hoping that she would, one day, play the Divine Miss M.

I am sure the loss is all mine, but of the Golden Age female crime writers I have found Agatha Christie the least interesting, despite her ingenious plotting and ability to create atmosphere. Mea Culpa, I suppose, but it would be reckless not to include Miss Marple in this list. Geraldine McEwan and Julia McKenzie have their admirers, but Joan Hickson is, surely, the Miss Marple? Her series (1984 – 1992) was certainly the most canonical and, if the anecdote is to be believed, Agatha Christie herself once sent a note to the younger Hickson hoping that she would, one day, play the Divine Miss M.

Small, aggressive, punchy and with hard earned bags under his eyes, Mark McManus was Taggart. Before he drank himself to death, McManus drove the Glasgow cop show, repaired its engine and polished its bodywork to perfection. It was Scottish Noir before the term had come into common parlance. Bleak, abrasive, unforgiving and with a killer theme song, Taggart was a one-off. The series limped on after McManus died but it was never the same again. (1983 – 1995)

Small, aggressive, punchy and with hard earned bags under his eyes, Mark McManus was Taggart. Before he drank himself to death, McManus drove the Glasgow cop show, repaired its engine and polished its bodywork to perfection. It was Scottish Noir before the term had come into common parlance. Bleak, abrasive, unforgiving and with a killer theme song, Taggart was a one-off. The series limped on after McManus died but it was never the same again. (1983 – 1995)

Who knows what the lady herself would have made of David Suchet’s Poirot? Her family are said to have approved, and for sheer over-the-top bravura, Suchet’s mincing and mannered portrayal has to be admired. The production values were always immense from day one in 1989 and by the time the series finished in 2013, every major work by Agatha Christie which featured Poirot had made its way onto the screen. The supporting cast was every bit as good, with Hugh Fraser as Hastings and Philip Jackson as the permanently one-step-behind Inspector Japp.

Who knows what the lady herself would have made of David Suchet’s Poirot? Her family are said to have approved, and for sheer over-the-top bravura, Suchet’s mincing and mannered portrayal has to be admired. The production values were always immense from day one in 1989 and by the time the series finished in 2013, every major work by Agatha Christie which featured Poirot had made its way onto the screen. The supporting cast was every bit as good, with Hugh Fraser as Hastings and Philip Jackson as the permanently one-step-behind Inspector Japp.

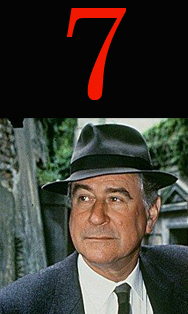

For me, the Golden Age Queen was Dorothy L Sayers and my permanent Best Ever Crime Novel is The Nine Tailors, so it is a relatively brief series (1972 – 1975) featuring Lord Peter Wimsey that makes its way into this list. Some DLS buffs refer the slightly more cerebral Edward Petherbridge version, but my vote goes to Ian Carmichael. He played up the more foppish and scatty side of Wimsey’s nature, but he also managed to convey, underneath the gaiety, the fact that Wimsey was something of a war hero, and his recovery from wounds and shell shock was due in no small part to his relationship with his former Sergeant, Mervyn Bunter.

For me, the Golden Age Queen was Dorothy L Sayers and my permanent Best Ever Crime Novel is The Nine Tailors, so it is a relatively brief series (1972 – 1975) featuring Lord Peter Wimsey that makes its way into this list. Some DLS buffs refer the slightly more cerebral Edward Petherbridge version, but my vote goes to Ian Carmichael. He played up the more foppish and scatty side of Wimsey’s nature, but he also managed to convey, underneath the gaiety, the fact that Wimsey was something of a war hero, and his recovery from wounds and shell shock was due in no small part to his relationship with his former Sergeant, Mervyn Bunter.

Just as on the printed page, TV crime series have more Detective Inspectors than you can shake a retractable police baton at. The first to make it into my selection is, perhaps, not so well known to the general reading public, but a firm favourite with those of us who kid ourselves that we are connoisseurs. Charlie Resnick is a creation of that most cerebral of crime novelists, John Harvey. He is distinctly downbeat and his ‘patch’ is the resolutely unfashionable midlands town of Nottingham. There were eleven novels featuring the jazz loving detective, but only two of them were televised. Lonely Hearts screened in three parts in 1992, while Rough Treatment had two parts, and was broadcast a year later. Both screenplays were written by John Harvey himelf, and Tom Wilkinson brought a lonely and troubled complexity to the main role.

Just as on the printed page, TV crime series have more Detective Inspectors than you can shake a retractable police baton at. The first to make it into my selection is, perhaps, not so well known to the general reading public, but a firm favourite with those of us who kid ourselves that we are connoisseurs. Charlie Resnick is a creation of that most cerebral of crime novelists, John Harvey. He is distinctly downbeat and his ‘patch’ is the resolutely unfashionable midlands town of Nottingham. There were eleven novels featuring the jazz loving detective, but only two of them were televised. Lonely Hearts screened in three parts in 1992, while Rough Treatment had two parts, and was broadcast a year later. Both screenplays were written by John Harvey himelf, and Tom Wilkinson brought a lonely and troubled complexity to the main role.

Van der Valk took us to Amsterdam for an impressive five series, based on the novels by Nicolas Freeling. Freeling tired of his creation, and killed him off after eleven novels. He resisted the clamour to resurrect him, but did write two more books featuring the late cop’s widow. The TV series was, by way of contrast, milked for all it was worth, and Barry Foster played Commissaris Piet van der Valk against authentic Dutch settings. Amsterdam’s reputation for sleaze, sex and substances did the series no harm at all in the eyes of British sofa-dwellers. Theme tunes are an integral part of any successful series and Eye Level took on a life of its own, improbably reaching No. 1 in the British pop charts in 1973. Noel Edmunds’ barnet is irresistible, is it not?https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvesdlGe-EI

Van der Valk took us to Amsterdam for an impressive five series, based on the novels by Nicolas Freeling. Freeling tired of his creation, and killed him off after eleven novels. He resisted the clamour to resurrect him, but did write two more books featuring the late cop’s widow. The TV series was, by way of contrast, milked for all it was worth, and Barry Foster played Commissaris Piet van der Valk against authentic Dutch settings. Amsterdam’s reputation for sleaze, sex and substances did the series no harm at all in the eyes of British sofa-dwellers. Theme tunes are an integral part of any successful series and Eye Level took on a life of its own, improbably reaching No. 1 in the British pop charts in 1973. Noel Edmunds’ barnet is irresistible, is it not?https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvesdlGe-EI

Most of my TV detectives are upright beings, not to say moral and public spirited. The East Anglian antique dealer Lovejoy was, by contrast, one of life’s chancers and, to borrow a phrase much used by local newspapers when some petty criminal has met a bad end, ‘a lovable rogue.’ Ian McShane and his impeccable mullet brought much joy to British homes on many a Sunday evening between 1986 and 1994. Lovejoy was always out for a quick quid, but like an Arthur Daley with a conscience, he always had an eye out for ‘the little guy’. McShane was excellent, but he had brilliant back-up in the persons of Phyllis Logan as the ‘did-they-didn’t-they’ posh totty Lady Jane Felsham, and the incomparable and much missed Dudley Sutton as Tinker Dill.

Most of my TV detectives are upright beings, not to say moral and public spirited. The East Anglian antique dealer Lovejoy was, by contrast, one of life’s chancers and, to borrow a phrase much used by local newspapers when some petty criminal has met a bad end, ‘a lovable rogue.’ Ian McShane and his impeccable mullet brought much joy to British homes on many a Sunday evening between 1986 and 1994. Lovejoy was always out for a quick quid, but like an Arthur Daley with a conscience, he always had an eye out for ‘the little guy’. McShane was excellent, but he had brilliant back-up in the persons of Phyllis Logan as the ‘did-they-didn’t-they’ posh totty Lady Jane Felsham, and the incomparable and much missed Dudley Sutton as Tinker Dill.

The TV version of the Vera books by Ann Cleeves is now into its quite astonishing tenth series and the demand for stories has long since outstripped the original novels. Close-to-retirement Northumbrian copper Vera Stanhope is still played by Brenda Blethyn, but her fictional police colleagues – as well as the screenwriters – have seen wholesale changes since it first aired in 2011. Why does the series do so well? Speaking cynically, there are several important contemporary boxes that it ticks. Principally, its star is a woman and it is set in the paradoxically fashionable North of England.The potential for scenic atmosphere is limitless, of course, but the core reason for its enduring popularity is the superb acting of Blethyn, and the fact that Cleeves has put together a toolkit of very clever and marketable elements. Vera will probably outlast me, and a new series is already commissioned for 2021.

The TV version of the Vera books by Ann Cleeves is now into its quite astonishing tenth series and the demand for stories has long since outstripped the original novels. Close-to-retirement Northumbrian copper Vera Stanhope is still played by Brenda Blethyn, but her fictional police colleagues – as well as the screenwriters – have seen wholesale changes since it first aired in 2011. Why does the series do so well? Speaking cynically, there are several important contemporary boxes that it ticks. Principally, its star is a woman and it is set in the paradoxically fashionable North of England.The potential for scenic atmosphere is limitless, of course, but the core reason for its enduring popularity is the superb acting of Blethyn, and the fact that Cleeves has put together a toolkit of very clever and marketable elements. Vera will probably outlast me, and a new series is already commissioned for 2021.

The creation of Cadfael was an act of pure genius by scholar and linguist Edith Pargetter, better known as Ellis Peters. Not only was the 12th century sleuth a devout Benedictine monk, but he had come to the cloisters only after a career as a soldier, sailor and – with a brilliant twist – a lover, as we learned that he has a son, conceived while he was fighting as a Crusader in Antioch. In the TV series which ran from 1994 until 1998, Derek Jacobi brought to the screen a superb blend of inquisitiveness, saintliness and a worldly wisdom which his fellow monks lacked, due to their entering the monastery before they had lived any kind of life. Modern times prevented the productions from being filmed in Cadfael’s native Shropshire, and they opted instead for Hungary!

The creation of Cadfael was an act of pure genius by scholar and linguist Edith Pargetter, better known as Ellis Peters. Not only was the 12th century sleuth a devout Benedictine monk, but he had come to the cloisters only after a career as a soldier, sailor and – with a brilliant twist – a lover, as we learned that he has a son, conceived while he was fighting as a Crusader in Antioch. In the TV series which ran from 1994 until 1998, Derek Jacobi brought to the screen a superb blend of inquisitiveness, saintliness and a worldly wisdom which his fellow monks lacked, due to their entering the monastery before they had lived any kind of life. Modern times prevented the productions from being filmed in Cadfael’s native Shropshire, and they opted instead for Hungary!

When my next series choice was aired in 1977, the producers had no confidence that either the name of its author, or that of its central character, would be a crowd puller, and so they called it Murder Most English. The four-part series consisted of adaptations of novels written by Colin Watson, and in print they were part of his Flaxborough Chronicles, twelve novels in total. Inspector Purbright, played by Anton Rodgers, is an apparently placid small town policeman, but a man who sees more than he says, and someone who has a sharp eye for the corruption and scheming endemic among the councillors and prominent citizens of Flaxborough – a fictional town loosely based on Boston, Lincolnshire, where Watson worked as a journalist for many years. The TV Purbright was perhaps rather more Holmesian – with his pipe and tweeds – than Watson had intended, but the original novels Hopjoy Was Here, Lonelyheart 4122, The Flaxborough Crab and Coffin Scarcely Used, were lovingly treated. Unusually, for a TV production, the filming was done in a location not too far from the fictional Flaxborough – the Lincolnshire market town of Alford, just 25 miles from Watson’s Boston workplace. Click this link to learn more about Colin Watson and his books.

When my next series choice was aired in 1977, the producers had no confidence that either the name of its author, or that of its central character, would be a crowd puller, and so they called it Murder Most English. The four-part series consisted of adaptations of novels written by Colin Watson, and in print they were part of his Flaxborough Chronicles, twelve novels in total. Inspector Purbright, played by Anton Rodgers, is an apparently placid small town policeman, but a man who sees more than he says, and someone who has a sharp eye for the corruption and scheming endemic among the councillors and prominent citizens of Flaxborough – a fictional town loosely based on Boston, Lincolnshire, where Watson worked as a journalist for many years. The TV Purbright was perhaps rather more Holmesian – with his pipe and tweeds – than Watson had intended, but the original novels Hopjoy Was Here, Lonelyheart 4122, The Flaxborough Crab and Coffin Scarcely Used, were lovingly treated. Unusually, for a TV production, the filming was done in a location not too far from the fictional Flaxborough – the Lincolnshire market town of Alford, just 25 miles from Watson’s Boston workplace. Click this link to learn more about Colin Watson and his books.