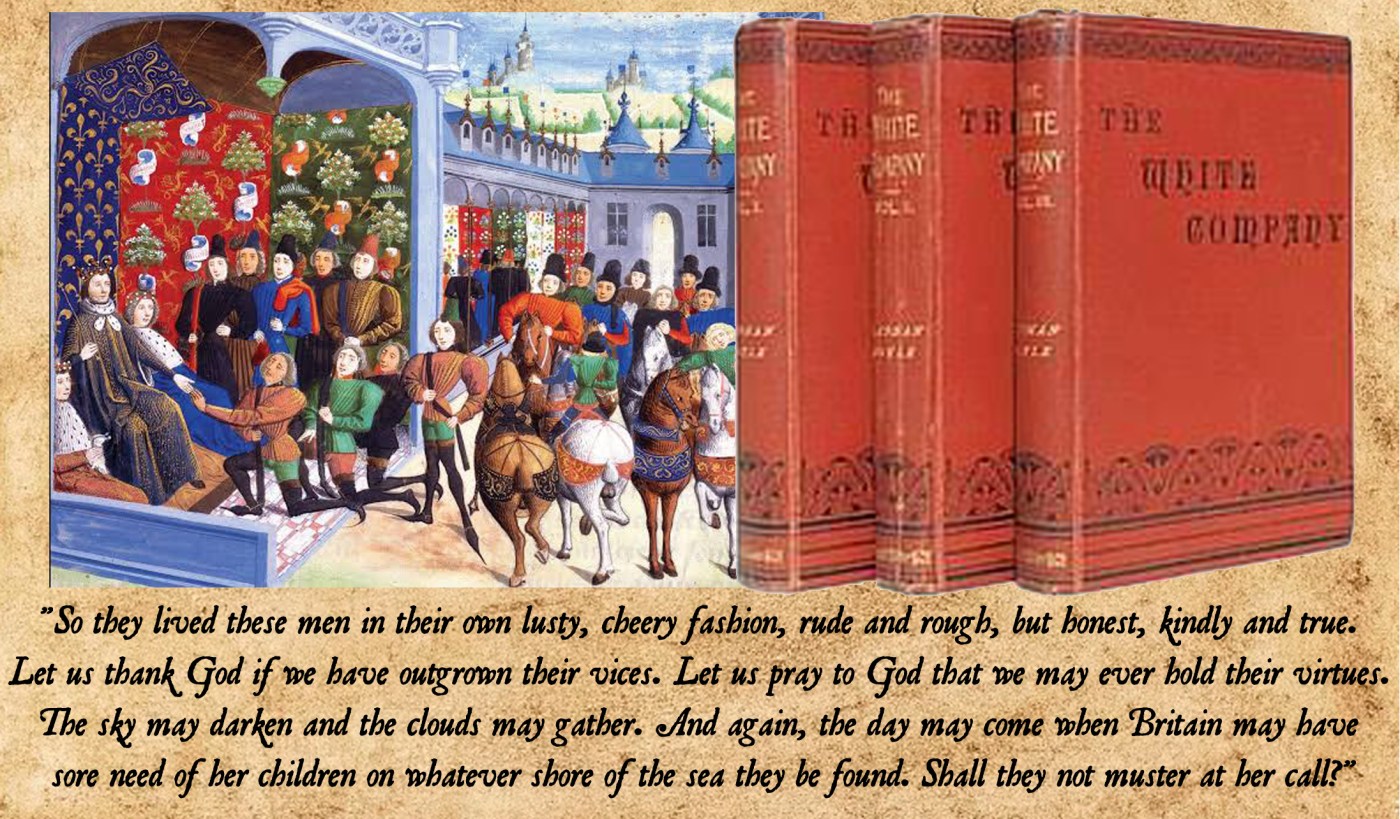

It is well known that Arthur Conan Doyle came to resent the immense commercial success of his greatest creation, Sherlock Holmes. Despite the wealth and fame he enjoyed as a result of those short stories and novellas, Conan Doyle was dissatisfied. Other full length novels were written. Micah Clarke (1889) was set in the Monmouth rebellion, while the Brigadier Gerard stories, boastful tales of a veteran of Napoleon’s army, began in 1894. The White Company (1891) was something quite different.The historical background to this novel is the 1367 campaign led by Edward (The Black Prince) to restore Peter (Pedro) as King of Spain.

The political allegiances are complex, and beyond the scope of this review. Suffice to say, the Prince’s forces in France are boosted by a body of men at arms and archers, led by Sir Nigel Loring, a Hampshire Knight, and his trusted retainers.Chief amongst these is Alleyn, a minor Saxon noble who has been educated by the monks of Beaulieu Abbey, and Samkin Aylward, a veteran archer. We follow these men across The Channel, and down through the battle scarred wastelands of South West France. I have no knowledge that Doyle ever visited the area for research purposes, but this is one of many magnificent descriptions of the terrain:

“The whole vast plane of Gascony and of Languedoc is an arid and profitless expanse in winter, save where the swift flowing Adour and her snow-fed tributaries, the Louts, the Oloron and the Pau run down to the sea of Biscay. South of the Adour, the jagged line of mountains which fringe the skyline send out long granite claws running down into the lowlands and dividing them into gavs or stretches of valley. Hillocks grow into hills and hills into mountains, each range overlying its neighbor until they soar up in a giant chain which raises its spotless and untrodden peaks, white and dazzling against the pale blue wintry sky.”

The biggest challenge facing writers of novels set in medieval times is dialogue and language. The earliest writer to come to terms with this was Sir Walter Scott. Many years later, Doyle gave us his version. In the 1960s Edith Pargetter (Ellis Peters) and Umberto Eco had their four penn’orth and, more recently, Sarah Hawkswood and Diane Calton Smith have given us their versions. The bottom line is that none of these writers have the faintest idea how people spoke to each other back then. All they can do is create a style and stick to it. The dialogue in this novel is grandiose and florid, full of improbable imprecations such as, “By the Holy Rood,” and “By my ten finger bones,”

After a cataclysmic battle between the outnumbered White Company and thousands of Spanish knights, the book ends improbably, but with a sense of glory and noble sacrifice. Doyle went on to work with distinction as a Medic in The Boer War and his son, Kingsley, served throughout The Great War, only to die of influenza in 1918. The final words of this novel confirm that Doyle had a deep sense of connection with the idea of English heroism and sense of duty. Perhaps the final words of this novel have a sense of prophecy about them:

“So they lived these men in their own lusty, cheery fashion, rude and rough, but honest, kindly and true. Let us thank God if we have outgrown their vices. Let us pray to God that we may ever hold their virtues. The sky may darken and the clouds may gather. And again, the day may come when Britain may have sore need of her children on whatever shore of the sea they be found. Shall they not muster at her call?”

Some modern readers will certainly find the book overly romantic, and wonder at the seeming implausibility of the chivalric code of honour. Historically, the narrative owes much to the chronicles and poems of Jean Froissart, whose account of the times continued to inspire creative artists. Indeed, Elgar’s Froissart Overture was composed just a year before The White Company was published. For me, rereading the book after many, many years was a sheer joy, and serves as a reminder of just how good a writer Doyle was.

The gunslinger, Jack ‘ Kid’ Durrant, is not only good with guns, but has ambitions to writer cowboy novels, rather after the celebrated author of Riders of The Purple Sage, Zane Grey (1872 – 1939) Not only that, the relationship between Lorne, Brooks and himself is, as they say, interesting. When Lorne is found dead, with Brooks and Durrant both missing, it is assumed that Durrant is the killer. Although it is not strictly a matter for the Railway Police, Jim feels personally involved, and visits the place where the three were last seen – the grounds of Bolton Abbey in Wharfedale. This allows Andrew Martin (left) to introduce us to what is known as one of the most dangerous rivers in Europe, The Strid. This natural phenomenon sees the River Wharfe forced through a narrow ravine, just a few feet wide. It has been described as the river ‘running sideways’, rather like a twisted ribbon and is believed to be prodigiously deep. No-one goes into it and ever comes out alive.

The gunslinger, Jack ‘ Kid’ Durrant, is not only good with guns, but has ambitions to writer cowboy novels, rather after the celebrated author of Riders of The Purple Sage, Zane Grey (1872 – 1939) Not only that, the relationship between Lorne, Brooks and himself is, as they say, interesting. When Lorne is found dead, with Brooks and Durrant both missing, it is assumed that Durrant is the killer. Although it is not strictly a matter for the Railway Police, Jim feels personally involved, and visits the place where the three were last seen – the grounds of Bolton Abbey in Wharfedale. This allows Andrew Martin (left) to introduce us to what is known as one of the most dangerous rivers in Europe, The Strid. This natural phenomenon sees the River Wharfe forced through a narrow ravine, just a few feet wide. It has been described as the river ‘running sideways’, rather like a twisted ribbon and is believed to be prodigiously deep. No-one goes into it and ever comes out alive.

Alex Pearl (left) isn’t a reluctant name-dropper, and walk on parts for Julian Clary and Kenneth Clarke (in Ronnie Scott’s, naturally) set the period tone nicely. 1984 was certainly a memorable year. I remember driving through the August night to be at my dying dad’s bedside, and hearing on the radio that Richard Burton had died. Just a few weeks earlier we had been blown away by Farrokh Bulsara at Wembley, while Clive Lloyd and his men were doing something rather similar to the English cricket team.

Alex Pearl (left) isn’t a reluctant name-dropper, and walk on parts for Julian Clary and Kenneth Clarke (in Ronnie Scott’s, naturally) set the period tone nicely. 1984 was certainly a memorable year. I remember driving through the August night to be at my dying dad’s bedside, and hearing on the radio that Richard Burton had died. Just a few weeks earlier we had been blown away by Farrokh Bulsara at Wembley, while Clive Lloyd and his men were doing something rather similar to the English cricket team.

consists of two first person accounts of events, that of Marsi and that of Stina. This, of course, raises the technical dilemma of Stina’s account. Because she is telling us what is happening in the winter 0f 1967, are we to assume that she is still alive? It is not quite such a conundrum as that of Schrödinger’s Cat but, outside the realm of supernatural fiction, the dead cannot speak.

consists of two first person accounts of events, that of Marsi and that of Stina. This, of course, raises the technical dilemma of Stina’s account. Because she is telling us what is happening in the winter 0f 1967, are we to assume that she is still alive? It is not quite such a conundrum as that of Schrödinger’s Cat but, outside the realm of supernatural fiction, the dead cannot speak.