Frank Marshal is a seventy year-old former senior detective. He lives in a former farmhouse in Snowdonia, and volunteers as a national park ranger. He has, as they say, baggage. His wife Rachel has dementia. His son committed suicide in that self same house. His daughter Caitlin lives in England with her waster of a boyfriend and their son Sam. A not-so-near neighbour, as the area is sparsely populated, is another retired from the justice system, but Annie Taylor was a High Court Judge. Now, her sister Megan has gone missing from her rented caravan in a hilltop trailer park.

The book has a prologue which describes a woman – time-frame presumably the present – being held against her will in a remote location. When Marshal discovers bloodstains beneath the decking of Megan’s caravan, a full police investigation kicks in. Megan’s errant son, Callum, had lived with her in the caravan. Annie and Marshal track him down to his (absent) father’s house. The youth tries to escape on his moped. Marshal pursues him, but only succeeds in running him off the road into a river. Marshal rescues him, but now Callum is in hospital, suffering from amnesia. Big question. Is the memory loss genuine or a pretence?

Marshal may be a gentle father, grandfather and former policeman, but he would never survive the current scrutiny that subtly shapes modern officers to the mould set by the metropolitan liberals who run the UK legal system. Only the knowledge of the disastrous consequences of him shooting a predatory salmon poacher prevents him from pulling the trigger while, when Caitlin’s lowlife partner – TJ – arrives in Wales demanding access to his son, Marshal has no compunction in planting several bags of marching powder (recently discovered hidden in Megan’s caravan) in TJ’s car. And if the local police should find the drugs, then who is he to correct their sums when they make two plus two equal five?P.

When the body of Annie’s sister is found dead on the beach at Barmouth, strangled with thin wire, Marshal has a grim thought running through his thoughts. The wire garotte was the favoured method of a notorious serial killer, Keith Tatchell years earlier. Now Tatchell is serving life imprisonment. Two equally horrific options spring to Marshal’s mind: was Tatchell wrongly convicted and is the real killer still out there?; is Meghan’s killer someone connected to Tatchell and seeking revenge?

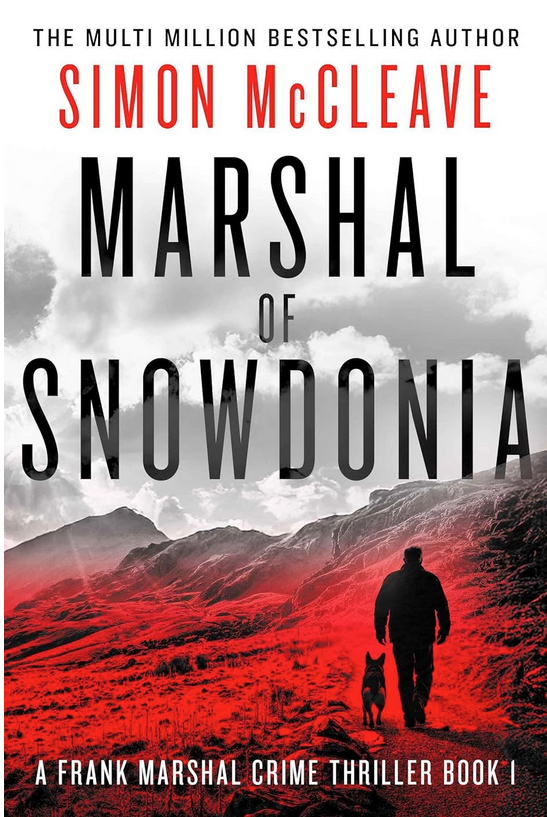

McCleave gives us a brilliant plot twist to reveal the true villain, but ends the novel with a suggestion that Frank Marshal may have more trouble on his hands in the next installment of what promises to be an addictive series.

I could no more be a professional writer than I could open the batting for England. The pressure to write something that sells and produces good reviews – and pays the bills – would, for me, be intolerable. Writers (unless they are TV celebrities) must constantly search for some draw, some hook, that will attract readers – and sales. I read hundreds of crime novels and, amid the gimmicks, the split time frames and the hysteria of desperate publicists, it is a relief to read a novel that is just impeccably written, with a solid narrative, and peopled by plausible characters. Marshal of Snowdonia is one such, and I can heartily recommend it. It was published by Stamford Publishing earlier this year.