Thomas True is the son of the Rector of Highgate. Now a sought after London suburb, in the early 18th century, at the time in which this novel is set, it was a country village. The young man has, for some years, been aware of his homosexuality and, unfortunately, so has his fire and brimstone father, who has done his best to beat out of his son what he sees as ‘the Devil’. Thomas has saved up his allowance and is determined to escape the misery.

Unknown to his parents, Thomas has been writing to his cousin Amelia in London, with a view to living with her and her parents. Within minutes of jumping down from the mail coach into the mire of a London street, he has been drawn into a world that is both breathlessly exciting and profoundly dangerous. The world of the molly houses in London was already well established, and would continue as a forbidden attraction well beyond the scandal of the Cleveland Street raid in 1889 in which Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor was implicated, although there has never been any conclusive evidence that he was a customer of this male brothel. A molly? There is a lengthy explanation here.

Thomas meets a young man called Jack Huffins who is quick to recognise the lad as a kindred spirit, and he introduces him to Mother Clap’s which is, I suppose, the eighteenth century equivalent of a gay nightclub. We also meet a significant figure in the story, a burly stonemason called Gabriel Griffin. Working on the recently completed St Paul’s cathedral is his day job, but by night he is the bouncer at Mother Clap”s. He is also a man in perpetual mourning, haunted by his wife and child who died together three years earlier.

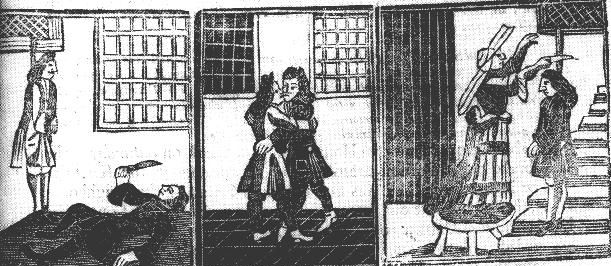

Hovering in the background to the revelry at Mother Clap’s is The Society for the Reformation of Manners. They actually existed, as did Mother Clap’s. The Society was, collectively, a kind of Mary Whitehouse (remember her?) of the day, and they existed to root out what they saw as moral decay, particularly of a sexual nature. They were far more sinister than the Warwickshire-born Christian campaigner however, as back then, men convicted of sodomy, buggery and ‘unnatural behaviour’ could be – and often were – hanged. The Society has inserted ‘ a rat’ into Mother Clap’s community. Quite simply, he is paid by his masters to identify participants, and give their names to two particularly repugnant officers of The Society, Justice Grimp and Justice Myre (Grimpen Mire, anyone?) The main plot centres on the search for the identity of ‘the rat’.

At times, the picture that AJ West (his website is here) paints of London is as foetid, grotesque and full of nightmarish creatures as that seen when zooming in to a detail in one of Hieronymus Bosch’s apocalyptic paintings. West’s London is largely based on history, but there are moments, such as when Thomas and Gabriel are captured by a tribe of street urchins in their dazzlingly strange lair, that the reader slips off the real world and drifts somewhere else altogether.

What the author does well is to show up the anguish and insecurity of the men who feel compelled to posture and pose as mollies, in an attempt to nullify the boredom of their respectable family lives. The bond of love that develops between Thomas and Gabriel is genuine, and certainly more powerful than the silly nicknames and grotesque flouncing at Mother Clap’s. The book ends with heartbreak. Or does it? Given that Gabriel is susceptible to ghosts, he is perhaps not a reliable narrator, and AJ West’s last few paragraphs suggest that the Society has, like the President of the Immortals at the end of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, ended its sport with Thomas and Gabriel. This paperback edition is out today, 3rd July, from Orenda Books.