For those who believe in geopsychology – the connection between place and the human mind – there is actually a place called Nettlebed. It is in Oxfordshire but not, as in the book, two hamlets, Little and Greater, divided by the River Thames. Given that the story mentions that, in living memory, older people remember the soldiers of the English civil wars, we e connection between Little Nettlebed and Greater Nettlebed is a simple punt ferry, operated by Pete Darling. Perhaps it is stretching things a little far, but the concept of the Ferryman in literature goes back into the mists of time and includes, of course, the mythical Charon, who carries passenger not across the placid upper reaches of the Thames, but a much darker river altogether. On one side of the river is the local ale house, frequented all too often by Pete Darling, and on the other bank, the farm owned by the elderly Joseph Mansfield. His wife is dead. His son and daughter in law are dead. All that remains are his five granddaughters – and his failing sight. Now, he lives as much by scent, touch and memory, as his milky eyes see only vague shapes and shadows.

Among the many joys of this book is the attention paid to the flora and fauna of the villages. My first thought was of the wonderful poem by Matthew Arnold, The Scholar Gypsy, where he writes, also of the Ofordshire landscape:

“Screen’d is this nook o’er the high half reaped field.

And here till sundown, shepherd, will I be.

Through the thick corn the scarlet poppies peep,

And round green roots and yellowing stalks I see

Pale pink convolvulus in tendrils creep;

And air-swept lindens yield

Their scent and rustle down their perfumed showers

Of bloom on the bent grass where I am laid.”

Xenobe Purvis gives us Agrimony, Figwort, Mignonette, Cow Parsley, Dog Roses, Foxgloves, Buttercups and Camomile. Be not distracted, however. The Nettlebeds are no balmy rural paradise, no Arcadia. We see a brutal rural custom which involves the burial of a woman who has died in childbirth. Local custom decrees that the six pallbearers must be women who are pregnant, as if to warn them that their fertility has consequences. When Ferryman Darling believes he has seen the Mansfield sisters turn themselves into dogs, some dismiss his claim as the imaginings of a drunk but, crucially, some people are only too ready to see this as a perfect explanation for why the five young women are so strange, and so aloof.

There are moments in this unsettling novel where I felt drawn into a Samuel Palmer painting. His England was full of mystery, a place where men and women were merely bystanders in an intense landscape of a setting sun sharing the canvas with a harvest moon, a land where thousand year-old traditions and phantom ancestors have a potent effect on present people.

The Ferryman is, perhaps, the key figure in The Hounding. As the river shrinks to a stream that people can easily wade through, his livelihood withers, and his daylight hours are seen through an alcoholic haze. He is the lightning conductor which seems to channel all the negative energy hovering over the hamlets. He sees – or thinks he sees – the five sisters for what they are:

“The fierce one, the pretty one, the tomboy, the nervous one, the youngest. That was what had frightened him the most: they were not mere doltish dogs. They were girls with teeth and claws.”

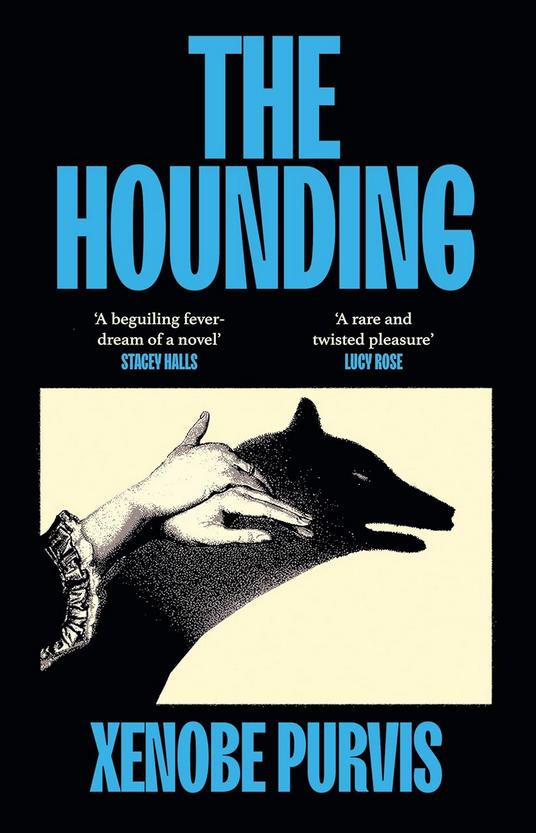

The novel ends with death and delusion, and the author, in narrative terms – and perhaps wisely – does not provide a definitive conclusion to the events in Little and Greater Nettlebed, but leaves us with the feeling we have after awaking from a strange and troubling dream. The Hounding is published by Hutchinson Heinemann and will be on sale from 26th June.