Although set in a beautiful village near Cirencester, with glowing limestone cottages, a jolly white-haired vicar, and the squire’s mansion up on its hill, this is as far away from a ‘Midsomer’ type Cosy Crime as you can get. Instead it is a beautifully written tale, full of poetry, some very dark corners and people who, if not severely damaged, are fighting their own demons. Anna Deerin, a former ballerina who had to quit through ligament damage has moved to the village of Upper Magna. She lives in a grace and favour cottage in the grounds of Fallow Hall. She lives rent free because she has undertaken to work and restore what was once the Hall’s extensive kitchen garden. She keeps chickens and earns a slender living by baking cakes and selling them – and her fruit and vegetables – at the weekly farmers’ market on the village green.

She lives in a kind of self-imposed exile, with no mobile phone and no current close friends. This all changes when, while attacking a long neglected part of the garden with a pick-axe, she finds human remains. Into her life comes Detective Inspector Hitesh Mistry, another London exile. He heads up the search for the identity of the skeleton – subsequently proved to be that of a woman. Like Anna, he is a complex individual. He is deeply immersed, emotionally, in a well of sadness caused by the recent death of his mother. While he respects his elderly father, the way that his mother was treated rankles with him. Although it seems nothing unusual in Indian families, he resents the fact that his mother was just seen as a cook, child-bearer and housemaid, while her obvious intellectual and emotional talents (she was a part-time hospital administrator) seemed to count for nothing in the family home. He has little left of her now, except the fragrance of her skin and cooking – and a treasured red cardigan which he describes, chillingly, as ‘empty’.

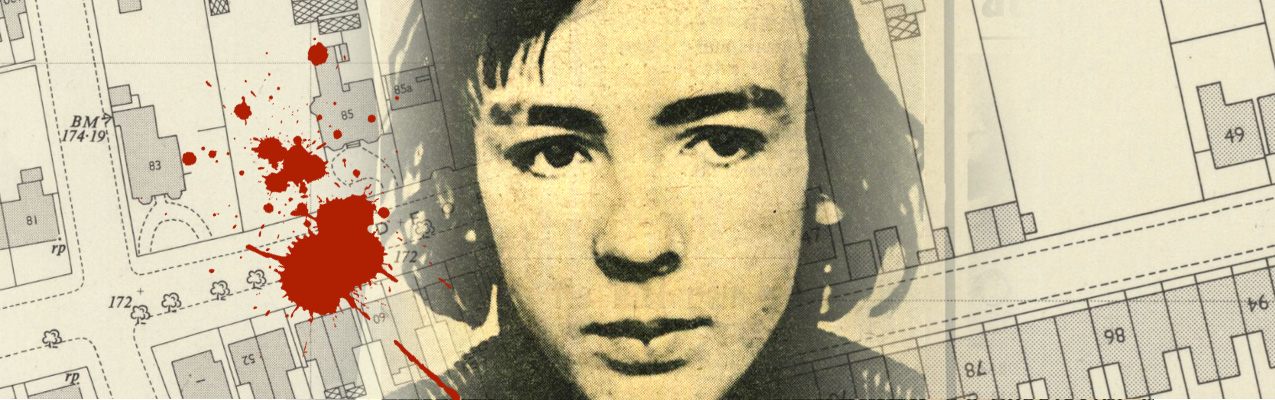

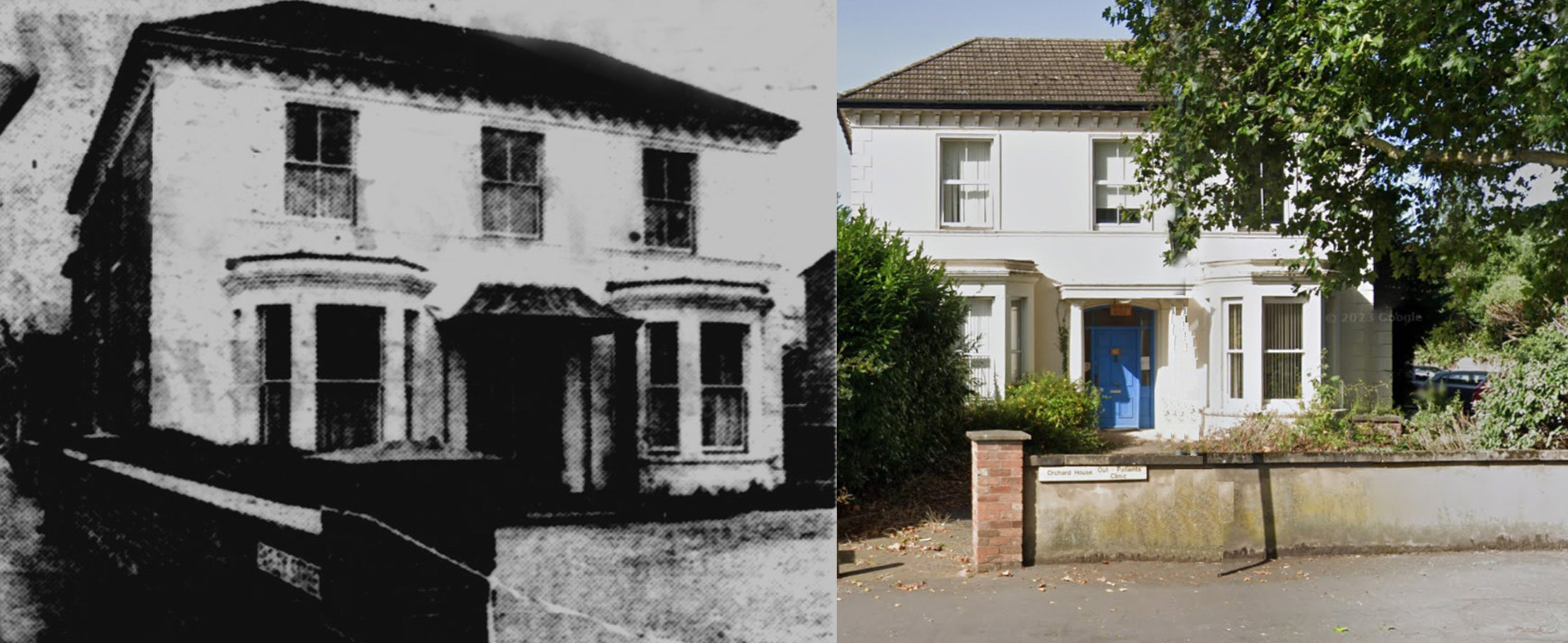

Bonnie Burke-Patel (left) intersperses contemporary events with brief but telling episodes from 1967. We meet a young woman, living locally (almost certainly in Fallow Hall) She has a younger brother, away at university. Her mother is rather inadequate, particularly at household skills, and her father is a domineering and demanding WW2 veteran, hideously disfigured by a facial injury. One morning, she escapes into Cirencester (to buy the ingredients for her own birthday cake) and meets a young Canadian man. There is an instant attraction and, after very little courtship she, belatedly – in the time-honoured phrase – loses her virginity.

This sets up the puzzle to perfection, but the author plays her cards very close to her chest. Mid way through the book there are so many questions. Is the authoritarian father related to Lord Blackwaite, the current Lord of the Manor? Is the body in the garden his daughter? Who tried to batter their way in to Anna’s cottage a couple of nights after she uncovered the remains?

Reviewing crime novels is not particularly difficult when the books are thrillers, police procedurals or basic whodunnits. The reviewer has a few simple tasks: outline the plot, describe the characters and setting, and then describe how well the book works. I am neither a professional writer nor a journalist, and so I tend to read books that I know I will be happy with. Just occasionally, there comes a book which challenges my ability to do it justice. I Died at Fallow Hall is one such.

As I said earlier, despite the familiar rural tropes, this is something rather special. The startling violence near the end, and the emotional intensity with which Anna empathises with – and is determined to identify – the girl whose skull she cradled in her hands on that fateful autumn afternoon, sets this novel aside as something very special. Putting on my reviewer’s hat I can answer the potential readers’ question, “What do I get.” In no particular order you get a murder mystery, a grim account of the cruelties that family members can inflict on each other, a poignant study of loneliness and isolation, a gimlet-eyed look at English class structure and, above all, a testimony to the power of love. From Bedford Square Publishers, this is available now.