The book starts in spectacular fashion. We are in London, in the summer of 1681. At Gresham College, the home of The Royal Society, senior scientist Robert Hooke (he of Hooke’s Law) has summoned the Great and the Good, including His Majesty King Charles II, and Harry Hunt, who we met in The Poison Machine and The Bloodless Boy (click the links to read reviews) to a public dissection. Wielding the blades and saws will be none other than the great polymath Sir Christopher Wren. The unfortunate corpse is an unknown woman who recently committed suicide at Bethlehem Hospital, the recently built refuge for the insane. Sir Christopher is hoping to show that the muscles of the cadaver can be made to twitch by manipulating various parts of the brain. The macabre experiment is well underway when the woman’s face is revealed. All hell breaks loose when Harry Hunt cries out:

“You must stop! She is no suicide from Bethlehem Hospital. Her name is Miss Diana Cantley. She was my neighbour in Bloomsbury Square.”

Sir John Reresby, Justice of The Peace for Westminster is called in, and he and Harry Hunt try to ascertain just when and how the body of Diana Cantley came to be substituted for the expected cadaver – that of a woman who took her own life in Bethlehem Hospital. Soon, a second aristocratic woman, Mrs Elizabeth Thynne, is reported missing but before her disappearance can be investigated, Harry is himself arrested. The body of the Bedlam Cadaver, Sebiliah Barton, is planted in his laboratory and Reresby, using Occam’s Razor*, assumed Harry is responsible for both deaths.

*A principle often attributed to. 14th–century friar William of Ockham that says that if you have two competing ideas to explain the same phenomenon, you should prefer the simpler one.

Harry, more by luck than judgment, escapes captivity, and after a life threatening encounter with the unforgiving waters of the Thames, struggles ashore in Rotherhithe, where he is sheltered by two women tailors. He finds the younger, Rachel – a Lithuanian – strangely attractive and they have a brief but passionate encounter. Thanks to a bizarre signaling mechanism invented by Robert Hooke, he is smuggled back to central London, where he faces a race against time to establish his own innocence and find the killer of Diana Cantley.

King Charles II features here, as in the previous novels, and Robert Lloyd paints a picture of a calm and decent man, at ease with himself, with a benign and generous soul. Be that as it may, Charles was no slave to marital loyalty, and he fathered many children by different lovers, hence the political problem, a simmering issue in this book, but one which was to boil over not many years down the line. Charles had no legitimate heir, and it was accepted that his brother James, would succeed him. This would pose a problem, as James was a devout Roman Catholic. Charles had a much favoured illegitimate son, James Scott Duke of Monmouth. A Protestant, he also appears in this novel, and readers who know their history will be aware that when Charles died in 1685, he was succeeded by James, and not long after, Monmouth was leader of an unsuccessful invasion force, which was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor, and its surviving followers brutally dealt with.

In addition to clearing his own name, finding out who murdered Diana Cantley and tracing Elizabeth Thynne, Harry is caught up in the search for a mysterious black box, said to contain evidence that King Charles was secretly married to the Duke of Monmouth’s mother, thus making Monmouth the rightful heir to the throne.

Harry Hunt is an unusual – but engaging – hero. His main quality is intelligence. Although no coward, he rarely comes off best in fisticuffs or swordplay. His ambition to marry Grace, Robert Hooke’s niece, is paramount, mainly for social reasons, but he is a man with needs, as shown by his brief dalliance with the enigmatic Rachel. The Bedlam Cadaver is impeccably researched, and its anchor points are the real life characters like Hooke, Wren, The King and Monmouth; above that, however, Robert Lloyd gives us a sparkling narrative, and the real sense that – nearly 350 years later – we are in the same room as his characters. The Bedlam Cadaver is published by Melville House, and is out now.

Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

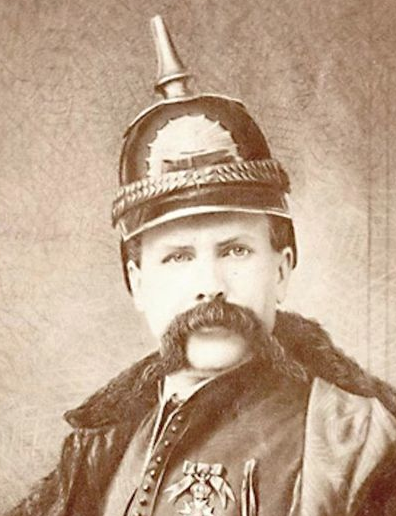

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence.

Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence. Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.