Ask ten different readers what they think qualifies as ‘noir’ and you will get ten different answers. Is it that everything is framed in a 1950s monochrome? Is it because all the participants behave badly towards each other, and have zero respect for themselves? Is it because we know that when we turn the final page, there will be no outcome that could be described as optimistic or redemptive? One quality, for me, has to be an unremitting sense of bleakness – both physical and moral – and this novel by CJ Howell (left) certainly has that.

Ask ten different readers what they think qualifies as ‘noir’ and you will get ten different answers. Is it that everything is framed in a 1950s monochrome? Is it because all the participants behave badly towards each other, and have zero respect for themselves? Is it because we know that when we turn the final page, there will be no outcome that could be described as optimistic or redemptive? One quality, for me, has to be an unremitting sense of bleakness – both physical and moral – and this novel by CJ Howell (left) certainly has that.

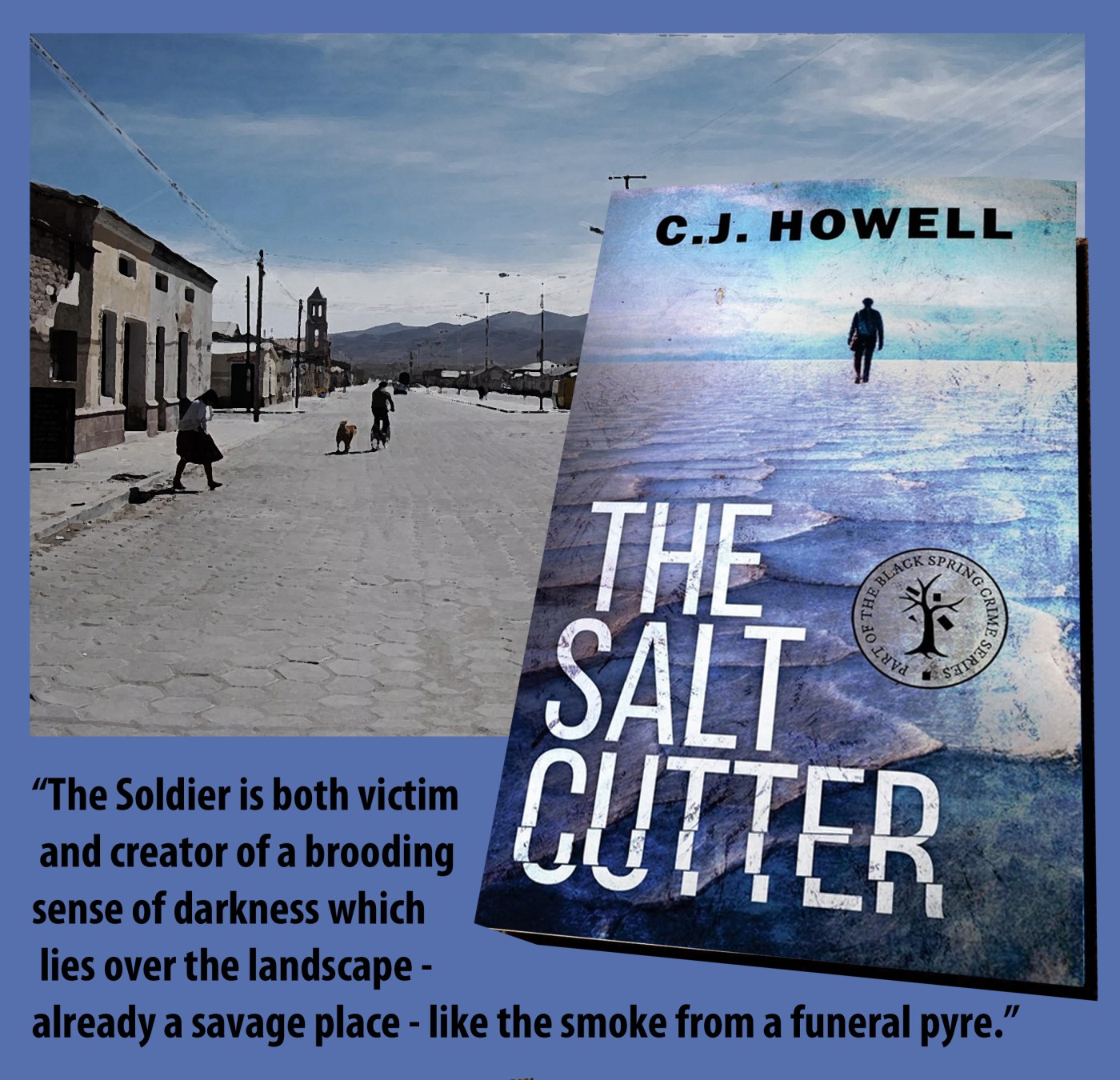

Set in Bolivia, The Salt Cutter centres on a young soldier – he is never named – who has deserted, and is on the run, with only his military boots, a rucksack, and his disassembled M16 machine gun for company. It is November 1991, and The Soldier fetches up in the desolate town of Uyuni, on the edge of the Salar de Uyuni, the world’s largest salt flats. Nowadays, there is something of a tourist industry but at the time when the book is set, the place was so bleak that even the rats had given up the ghost and moved elsewhere.

Along with a man called Hector Anaya, who had arrived with his family on the same ramshackle bus that brought him to Uyuni, The Soldier gets a job with a small crew cutting salt out on the flats, and he strikes up a cautious friendship with a woman called Maria, the town baker. He as also attracted a little follower, in the shape of a boy who makes a precarious living shining shoes.

The Soldier is expecting to be followed to Uyuni by his military masters, but why they would bother, for one random young man from an army of tens of thousands is not made clear. Two agents of the army do arrive and The Soldier kills them. The town’s policeman, El Gordo, has a realistic view of what law and order means in his town:

“Law? There is no law.”

El Gordo sucked at his cigarette between gasping breaths. ”

“There is money and there are guns. In a place like this, that isn’t much money, so the guns have the power. Here, the law is guns. Here, you are the law.”

The policeman knows that if the army come in force for The Soldier, they may exact a terrible price on the town, so the young man allows El Gordo to drive him a safe distance from the town, and he ends up in a remote settlement near a lithium mine.

At this point, the book takes an unusual narrative turn, as it jumps back in time – three days before we first meet The Soldier – and we are in a large city, presumably the capital La Paz, where Hector Anaya is a college lecturer. When two of his students are arrested by the army, he goes home, bundles his family and a few belongings into their car, and they drive off, putting as much distance between themselves and the city as possible. Eventually, hundreds of miles later, the car has pretty much been driven into the ground, which is how Hector, his wife and children, end up on the bus that brings The Soldier into Uyuni.

We then rejoin The Soldier, where he has the chance to board a bus which will take him even further from Uyuni but, instead, he gets a ride with a driver taking a tanker full of lithium brine to meet the railway at Uyuni. He finds that the army have indeed arrived, and the town, which was a bleak place before, now carries the stench of death.

Dead dogs lined the street. Strays, shut and then left to rot where they lay. Clumps of fur slowly peeled away by the wind. Sunken rib cages and smiles of death. Leathered gums shorn back high on the tooth. Fangs bared for eternity.

The conclusion of this powerful novel is all about sacrifice and redemption – of a sort. Throughout, the writing is vivid and visceral, sometimes literally so. The Soldier is both victim and creator of a brooding sense of darkness which lies over the landscape – already a savage place – like the smoke from a funeral pyre. The Salt Cutter is published by The Black Spring Press and is available now.