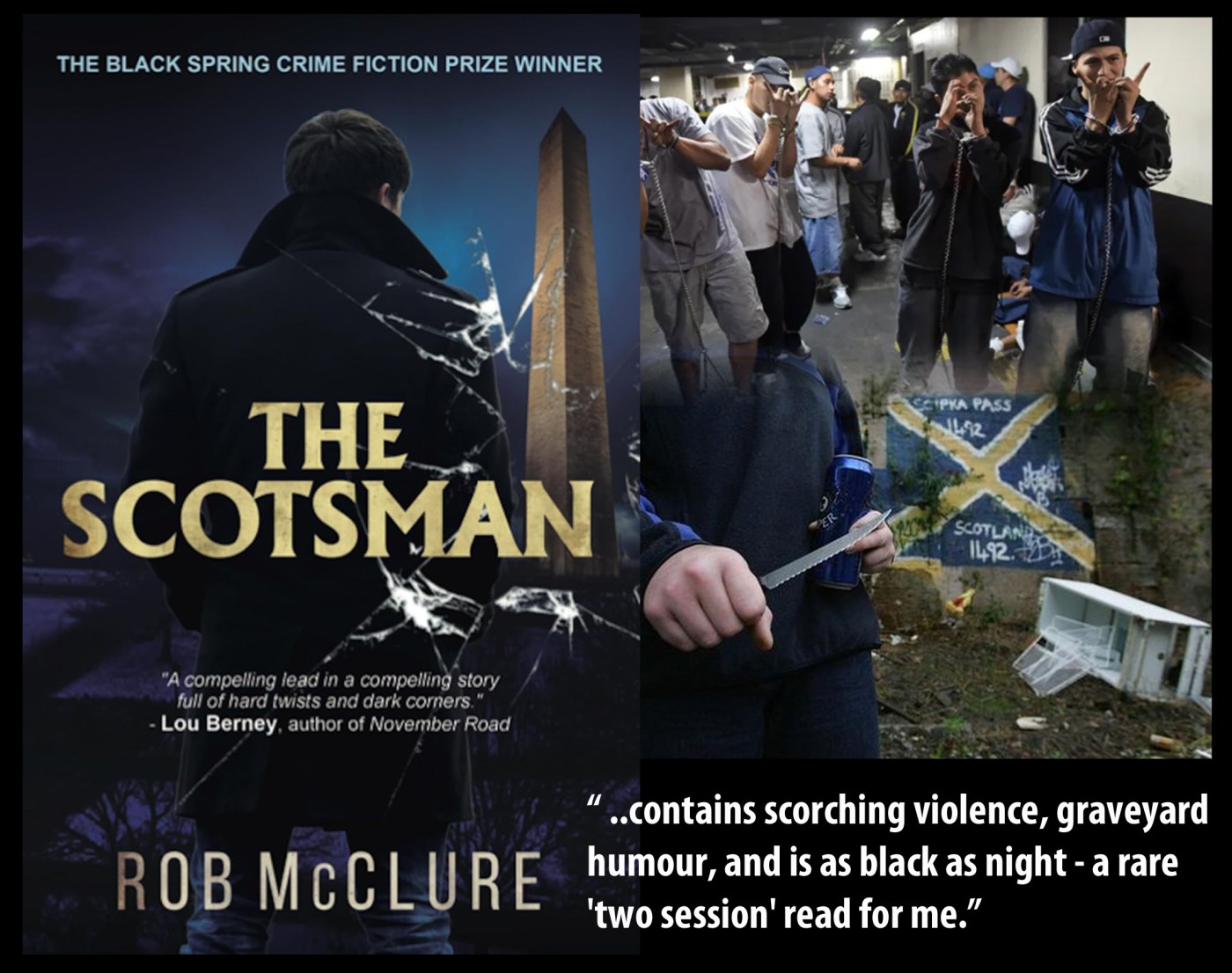

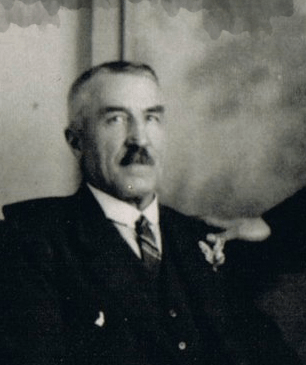

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

Charles ‘Chic’ Cowan is a Glasgow cop, and his daughter, Catriona, was studying at an Washington DC university when she was shot dead on the Metro. CCTV footage shows that her assailants were two black men, one of whom later ends up dead as a result of feuding between drug gangs. The local police remain mystified as to who the other shooter was, and they are also baffled by an apparent lack of motive, and the fact that the shooting – at close range with a small calibre pistol – has all the hallmarks of a contract killing. Cowan travels to DC in an attempt to discover the truth.

Our man is a synthesis of every Scottish copper we have ever read about. He is undoubtedly intelligent, but abrasive in his speech and manner. He used to like a drink or six but is now ‘on the wagon’, and has a jaundiced view of humanity, hence a nice collection of one-line gags. He recalls a fracas he was involved in at a family wedding in an insalubrious district of Glasgow:

“Easterhouse was the kind of place Ethiopia held rock concerts for.”

Cowan has long since separated from Catriona’s mother, and the more he investigates her life in the American capital, the more he realises how little he knew her. To start with, she was a lesbian, and it is when he discovers her relationship with a political journalist that he realises her murder is connected to something rotten in the state of American politics.

The closer he gets to the reason for his daughter’s murder, the more dangerous the men who are sent after him, but one by one, they come to rue the fact that the back streets of Glasgow make the sidewalks of Washington Highlands/Bellevue look like a Disney theme park by comparison. It is in places like Possilpark and Govan that Cowan learned every dirty trick in the book, and one involves a very inventive use of a piece of plywood, a razor blade, a length of duct tape and some knicker elastic. As for inducing a pursuer to ‘fall off’ a Metro platform thus making the acquaintance of the third rail, it is straight out of Cowan’s Glasgow playbook.

The Scotsman contains scorching violence, graveyard humour, and is as black as night – a rare ‘two session’ read for me. I don’t do star ratings, but if I did, it would be a five. I wasn’t fussed about the romantic interlude, but if it gives Cowan an excuse to return and cull a few more DC lowlife, then I’ll give his moments of passion a thumbs-up. The book is published by Black Spring and is available now.