Wisbech is a town in the fenland area of Cambridgeshire, and that is where I live. At which point some unkind wag will usually comment, “Well, I suppose someone has to.” That slight is not undeserved, as much of the place is pretty grim. It has some pretty Georgian and Victorian architecture, but in recent years it has had the stuffing knocked out of it by immigration. Add to that the disease infecting so many similar places in the country, that of the shops we knew and loved (but not patronised enough, sadly) being replaced with a seemingly endless supply of charity shops, mobile phone stores, bookies, coffee shops and pound stores. The town has featured peripherally in some novels; perhaps the brewery that featured in Graham Swift’s Waterland was our our own Elgoods; the town makes a brief appearance in my favourite crime novel, Dorothy L Sayers’ The Nine Tailors, gets a passing mention in some of Jim Kelly’s novels, but now there is a novel firmly centred in the town.

The legend of King John’s lost treasure is an intriguing one, and Diane Calton Smith (left) cleverly reimagines it in her novel In The Wash. I am not normally a fan of split time narratives, but she does it beautifully here, with the events of October 1216 being mirrored perfectly by a present day story beginning, also, in October. Perhaps ‘mirror’ is not the best metaphor – the two stories are more like a melody and its counterpoint in music, each complementing the other. In 1216 we meet Rufus, a young clerk under the tutelage of Father Leofric, a priest at Wisbech Castle, and the entire establishment is waiting for the arrival of King John, who is to make a break in his journey from Bishop’s Lynn to Newark. In present day Wisbech, Monica Kerridge is the curator of The Poet’s House Museum, an establishment dedicated to the life and work of celebrated Georgian poet Joshua Ambrose.

The legend of King John’s lost treasure is an intriguing one, and Diane Calton Smith (left) cleverly reimagines it in her novel In The Wash. I am not normally a fan of split time narratives, but she does it beautifully here, with the events of October 1216 being mirrored perfectly by a present day story beginning, also, in October. Perhaps ‘mirror’ is not the best metaphor – the two stories are more like a melody and its counterpoint in music, each complementing the other. In 1216 we meet Rufus, a young clerk under the tutelage of Father Leofric, a priest at Wisbech Castle, and the entire establishment is waiting for the arrival of King John, who is to make a break in his journey from Bishop’s Lynn to Newark. In present day Wisbech, Monica Kerridge is the curator of The Poet’s House Museum, an establishment dedicated to the life and work of celebrated Georgian poet Joshua Ambrose.

Rufus and his fellow clerks can only watch in awe from a distance as the King and his retinue arrive. Beset by political troubles both at home and abroad, the King appears tense and distracted at the lavish feast prepared for him, but his mood worsens when he receives shocking news from one of his courtiers, freshly arrived at the castle. His baggage train, a mile long and consisting of lumbering bullock carts and hundreds of men has fallen foul of the capricious tide as they attempted to ford the river mouth where it meets The Wash – with catastrophic results. In the days that follow, Rufus is called upon to catalogue the battered remains of the king’s wagons and the scores of of corpses washed up on the sea banks.

Back in the present day, Monica and several other town worthies become involved with a new group being set up to try to get to the bottom of the enduring mystery of what actually happened on that day in October 1216 and – more importantly – establish exactly where the abortive attempt to cross from Norfolk into Lincolnshire was made.

It is an established fact that King John died not long after his fateful sojourn in Wisbech, and was succeeded – at least in name – by his nine year-old son. Rufus becomes involved in a dangerous search for one particular item of John’s lost treasure – an item so precious that powerful interests in the land think little of murder in order to gain the prize. The search by Monica and her friends is less perilous, but they uncover a mystery just as intriguing.

Diane Calton Smith lets her two narrative melodies weave their magic and cleverly keeps the two time lines running almost exactly parallel, just separated by the eight centuries. Then, to extend the musical metaphor, the two themes resolve together in an very satisfying cadence to bring the piece to an end. I loved this book. Yes, the local interest intrigued me, but this is writing of the highest quality, backed by scrupulous historical research, a genuine sense of place, and shrewdly observed characters. In The Wash is published by New Generation Publishing and is available now

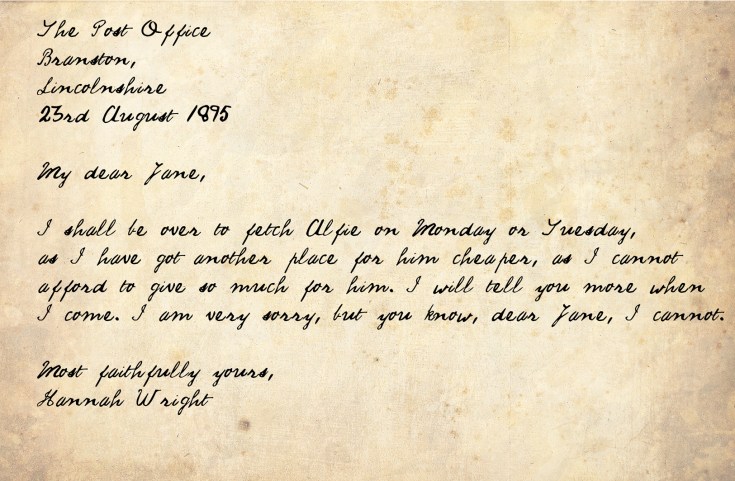

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

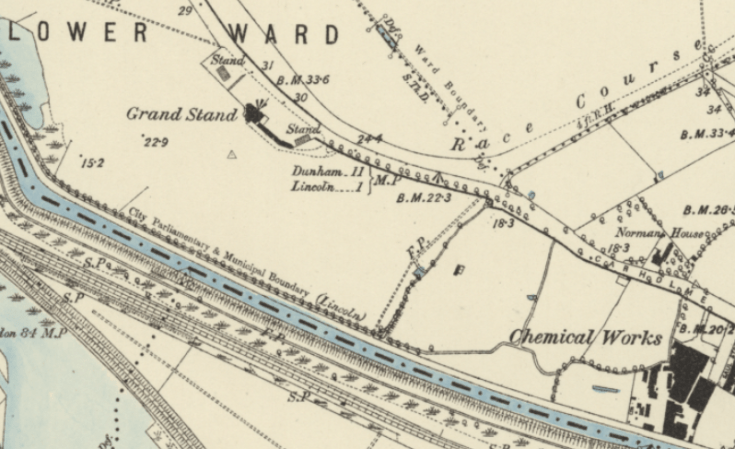

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.