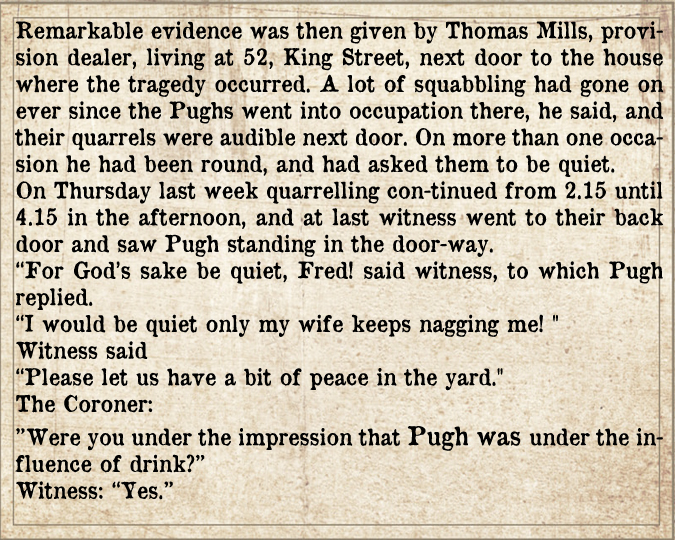

SO FAR: It is late afternoon on Thursday 19th March, 1921. Motor mechanic Frederick Pugh (47) has spent most of the day drinking in various Leamington pubs, and he has returned to the house he shares with his wife, Constance Ethel Pugh, at 50 King Street. Rows between the two are frequent and always noisy. The next door neighbour has come to remonstrate with Pugh, who is now outside the house. Pugh complains that his wife is always nagging him and goes back indoors.

The neighbour, Thomas Mills, returns to his own house, but then hears two loud bangs. He goes to look through the window of number 50, and seeing Mrs Pugh lying on the floor, runs into the town until he finds a policeman, Police Sergeant Pearson, who was on duty where Regent Street crosses The Parade.

Pearson was later to give this evidence:

“I was on duty on the Parade at the Regent Street crossing when Mills called me. Upon arriving at 50, King Street, I knocked at the back door, but received no reply. Looking through the kitchen window I saw a revolver lying in front the fire. I knocked again, but there was still response, so I decided to break in. Upon opening the door, Pugh put his face round the door and looked at me. His face was badly injured and covered with blood, and he was staggering about. I took hold of him and said ” What’s the matter? “

I assisted the man to the kitchen and laid him on the floor, having first taken charge of the revolver. Two chambers had been fired, and one had missed fire. One of the spent cartridges had been struck twice. When I loosened Pugh’s collar, the man said ” Let me get up,’’

After calling a doctor, I examined the house. The woman was lying on her back with her head under the sink, and she was quite dead, with blood-marks on the right side of the face. The appearances were that the shots had been fired at close range. The condition of the room did not suggest a struggle. The woman had been washing, and the utensils were in their correct position. By this time Pugh had become unconscious and upon following up my examination I found bloodmarks on the stairs and on the pillow on the bed.”

Constance Pugh was beyond mortal help, and her body was removed to the mortuary, but Frederick Pugh was rushed to the Warneford Hospital.

On the following Tuesday the inquest into Constance Pugh’s death was opened, and the sad state of the Pughs’ marriage was laid bare. This report is from The Leamington Courier:

“The first witness called was Mrs. J. H. Cooke, sister of Mrs. Pugh, who said that deceased was Pugh’s second wife. Pugh served during the war.

The Coroner: ‘Did you know the conditions under which they lived?’

Witness: ‘They were’nt very happy’

‘Did your sister’s husband ill-treat her and keep the children short of food?’

‘Yes, he had an abnormal temper.’

Witness proceeded to say that one day last week she had a conversation with her sister relative to Pugh and deceased then said that her husband had threatened to “do her and the children in.”

He had said this many times that they did not take him seriously.

The Coroner: ‘On this particular occasion had he used the expression because she had asked for food for the house?

‘Yes.’

Mrs. Cooke said that one of the sons lived at Luton, Pugh’s native town, and a daughter was in a home in London.

Foreman (Mr. R. E. Moore); ‘Was Pugh usually sober when he made these threats?’

Witness: ‘I was not there whenhe used them, but my sister said he had taken to drink again.’

‘You didn’t know much about the man himself?’ asked the Coroner.

“I simply hated him!” exclaimed the witness in reply.

The Foreman : Did you know that Pugh kept firearms in the house?

‘No, I shouldn’t have gone there had I known that he did.’

Mrs. Ada Key, another witness, living at 19 Plymouth Place, said the deceased had often complained of her husband’s treatment of her. and alleged that he kept the children short of food. He had a very bad temper. ‘My sister to come down to my house to get something to eat,’ continued the witness, ‘for she couldn’t get enough for the children at home.”

The Coroner: ‘You knew by her actions that she was not being supported properly at home?’

Witness: ‘Yes.’

‘Did she ever complain her husband drinking?’ asked the Coroner.

At this point the witness broke down, and the Coroner did not press his questions. “

Mr. E. F. Hadow (Coroner for Mid-Warwickshire) did eventually reconvene the inquest, but his optimism that Frederick Pugh would be able to attend to account for his crime was unfounded. Pugh eventually died, still in hospital, on Friday 2oth May. There only remained the technicality of deciding if Pugh was in his right mind when he shot his wife and then turned the gun on himself.

As with many of these stories, there are always the children who become victims of adult misdeeds. The Pughs had two children. In the census which was held in the summer of 1921, an Arthur Frederick Pugh, born in 1920 and listed as grandson, was living in Leamington in a house, the head of which was Edith Jones, born in Bishops Itchington, and almost certainly Constance Pugh’s mother. Sadly, the next time we hear of Arthur Frederick Pugh it is as a casualty in WWII. His body lies in Madras War Cemetery. Arthur was a cook in the Army Catering Corps. He was working at a military hospital in Burma. While walking around the hospital grounds he was shot by a sniper in a tree and killed on 28th April 1945 just two weeks before the end of the war in Europe. Peter Colledge reminded me that the war in the Far East was to continue until August, days after the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Thanks to Julie Pollard (a relative) for this information.

As with many of these stories, there are always the children who become victims of adult misdeeds. The Pughs had two children. In the census which was held in the summer of 1921, an Arthur Frederick Pugh, born in 1920 and listed as grandson, was living in Leamington in a house, the head of which was Edith Jones, born in Bishops Itchington, and almost certainly Constance Pugh’s mother. Sadly, the next time we hear of Arthur Frederick Pugh it is as a casualty in WWII. His body lies in Madras War Cemetery. Arthur was a cook in the Army Catering Corps. He was working at a military hospital in Burma. While walking around the hospital grounds he was shot by a sniper in a tree and killed on 28th April 1945 just two weeks before the end of the war in Europe. Peter Colledge reminded me that the war in the Far East was to continue until August, days after the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Thanks to Julie Pollard (a relative) for this information.

The older child, Tessa Vernie Yvonne Pugh (thanks again to Julie Pollard) was born in 1913. She was brought up by Constance’s brother Leonard. Records show that she married a man called Felix Jackson at Stratford in 1939. The 1939 register shows them living at 128 Tavern Lane Stratford. She died in 1973, her husband having passed away two years earlier.

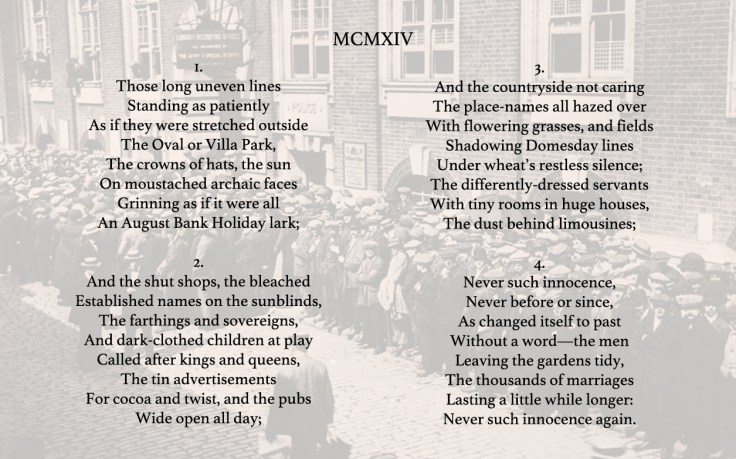

Was Frederick Pugh driven to commit murder by some awful residual damage he had incurred during the Great War? One newspaper report suggests that he had come home “with a piece of bullet lodged in his head.” He would not have been the only man damaged by the horrors of 1914 – 18, but we shall never know. The only certainty is that a fatal combination of anger and drink – and possibly war trauma – cost two people their lives on that March afternoon.

Cragg is instructed to ride out to a lonely moorland farmhouse, and what he finds surpasses any of the previous horrors his calling requires him to confront. He finds an entire family slaughtered, by whose hand he knows not, unless it was the husband of the house, himself hanging by a strap hooked over a beam. To add even more mystery to the grisly tableau, Cragg learns that the KIdd family were members of a bizarre dissenting cult which encourages its members into acts of brazen sexuality. Then, in a seemingly unconnected incident, the gardener at a nearby mansion, trying to improve the drainage under his hothouse, discovers another body. This corpse may have been in the ground for centuries, as it has been partly preserved by the peat in which it was buried. When Fidelis conducts an autopsy, however, he concludes that the body is that of a young woman, and was probably put in the ground within the last decade or so.

Cragg is instructed to ride out to a lonely moorland farmhouse, and what he finds surpasses any of the previous horrors his calling requires him to confront. He finds an entire family slaughtered, by whose hand he knows not, unless it was the husband of the house, himself hanging by a strap hooked over a beam. To add even more mystery to the grisly tableau, Cragg learns that the KIdd family were members of a bizarre dissenting cult which encourages its members into acts of brazen sexuality. Then, in a seemingly unconnected incident, the gardener at a nearby mansion, trying to improve the drainage under his hothouse, discovers another body. This corpse may have been in the ground for centuries, as it has been partly preserved by the peat in which it was buried. When Fidelis conducts an autopsy, however, he concludes that the body is that of a young woman, and was probably put in the ground within the last decade or so.

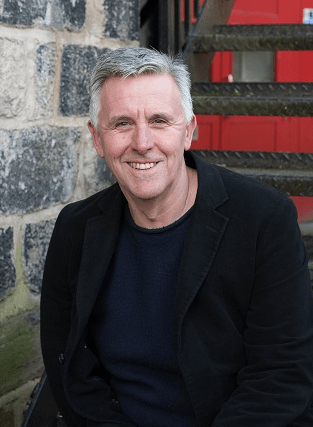

Jimmy Mullen is a former Royal Navy man, but he has fallen on hard times. He served in The Falklands and has recurrent PTSD. He has served a jail term for manslaughter after intervening to stop a girl being slapped around and, until recently, lived out on the streets of Newcastle, among the city’s many homeless. Now, for the first time in years, he has a job – working for a charity – and a proper roof over his head. Author Trevor Wood (left) introduced us to Mullen in

Jimmy Mullen is a former Royal Navy man, but he has fallen on hard times. He served in The Falklands and has recurrent PTSD. He has served a jail term for manslaughter after intervening to stop a girl being slapped around and, until recently, lived out on the streets of Newcastle, among the city’s many homeless. Now, for the first time in years, he has a job – working for a charity – and a proper roof over his head. Author Trevor Wood (left) introduced us to Mullen in  Gadge becomes the victim of one of these assaults, but when he is woken up from his drunken stupor by the police, he is covered in blood – most of it not his – and in an adjacent alley lies the corpse of man battered to death with something like a baseball bat. And what is Gadge clutching in his hands when the police shake him into consciousness? No prizes for working that one out!

Gadge becomes the victim of one of these assaults, but when he is woken up from his drunken stupor by the police, he is covered in blood – most of it not his – and in an adjacent alley lies the corpse of man battered to death with something like a baseball bat. And what is Gadge clutching in his hands when the police shake him into consciousness? No prizes for working that one out! I have spent longer on the biographical details of John Betjeman because, in what was his longest and most profound poem, Summoned By Bells (1960), he writes his autobiography in blank verse.

I have spent longer on the biographical details of John Betjeman because, in what was his longest and most profound poem, Summoned By Bells (1960), he writes his autobiography in blank verse.

So what are we to make of Betjeman’s poetry today, the age of cancel culture, triggered university graduates, and the most virulent class war that I can remember in my seventy-odd years of being sentient? He has been described – by lesser writers – as mediocre. His prevailing themes included the foibles and rituals of the English middle class, churches, railways, Victorian buildings and London. Hardly the stuff to bring him to the cutting edge of the literary razor in 2022, admittedly. But his detractors – or those who see him as an anachronistic bumbler, mugging it up for TV cameras and radio microphones – miss the point, big time. Time and space forced me to ignore the sheer joy found in his description of railway stations, gymkhanas, Edwardian suburbs and churches and look at his compassion. In

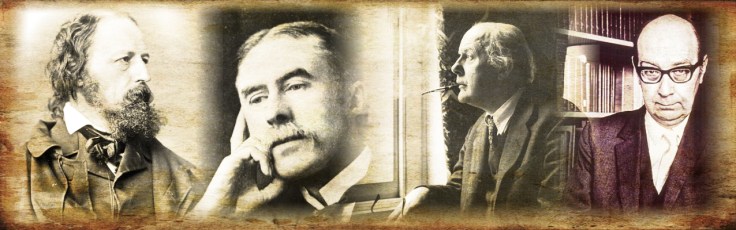

So what are we to make of Betjeman’s poetry today, the age of cancel culture, triggered university graduates, and the most virulent class war that I can remember in my seventy-odd years of being sentient? He has been described – by lesser writers – as mediocre. His prevailing themes included the foibles and rituals of the English middle class, churches, railways, Victorian buildings and London. Hardly the stuff to bring him to the cutting edge of the literary razor in 2022, admittedly. But his detractors – or those who see him as an anachronistic bumbler, mugging it up for TV cameras and radio microphones – miss the point, big time. Time and space forced me to ignore the sheer joy found in his description of railway stations, gymkhanas, Edwardian suburbs and churches and look at his compassion. In  Was there ever such a yawning gulf between a man and his words as with AE Housman? By all accounts he was prissy, pedantic and and vindictive towards Cambridge undergraduate pupils who failed to meet his expectations in their studies of the classics. He was memorably described as “

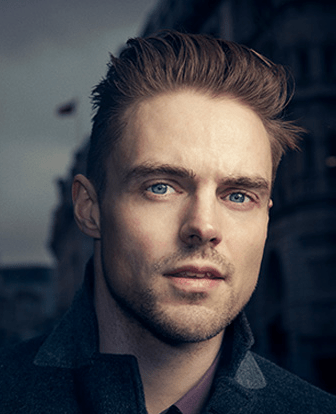

Was there ever such a yawning gulf between a man and his words as with AE Housman? By all accounts he was prissy, pedantic and and vindictive towards Cambridge undergraduate pupils who failed to meet his expectations in their studies of the classics. He was memorably described as “ It is a matter of record that the love of Housman’s life was a fellow Oxford student, Moses John Jackson (right). The passion was in one direction only, and Jackson later placed some geographical distance between himself and Housman. So what has this to do with the poetry? The pervading theme in A Shropshire Lad is a longing, a yearning for something that can never come again, places and people irretrievably lost, a memory of earlier years. Housman never courted a lass

It is a matter of record that the love of Housman’s life was a fellow Oxford student, Moses John Jackson (right). The passion was in one direction only, and Jackson later placed some geographical distance between himself and Housman. So what has this to do with the poetry? The pervading theme in A Shropshire Lad is a longing, a yearning for something that can never come again, places and people irretrievably lost, a memory of earlier years. Housman never courted a lass

If you can get your head around the idea, Knox (left) plays himself here and the book is a series of statements, made to a fellow author by a cast of characters who were part of Zoe’s life. Initially, we have her parents, her twin sister, and an array of other young people who were part of her life prior to her disappearance after a night clubbing in Manchester, but as Zoe Nolan is gradually transformed into someone with a huge bag of secrets slung over her shoulder, more voices are added to the account.

If you can get your head around the idea, Knox (left) plays himself here and the book is a series of statements, made to a fellow author by a cast of characters who were part of Zoe’s life. Initially, we have her parents, her twin sister, and an array of other young people who were part of her life prior to her disappearance after a night clubbing in Manchester, but as Zoe Nolan is gradually transformed into someone with a huge bag of secrets slung over her shoulder, more voices are added to the account. The statements made by the ‘witnesses’ give us an overview – albeit imperfect, given that we don’t know who to trust – of the hours leading up to Zoe’s disappearance, and the months and years which led up to a promising young singer being rejected by the Royal Northern Collegee of Music and having to settle for a less prestigious place at Manchester University.

The statements made by the ‘witnesses’ give us an overview – albeit imperfect, given that we don’t know who to trust – of the hours leading up to Zoe’s disappearance, and the months and years which led up to a promising young singer being rejected by the Royal Northern Collegee of Music and having to settle for a less prestigious place at Manchester University.

I’ll start with Tennyson, but offer a word of caution. Look hard at his poetry and you may not see obvious indicators of his Lincolnshire roots. But let me turn it on its head. Visit the village of Somersby, an isolated and lonely hamlet deep in the Wolds of Lincolnshire, the place where he spent his boyhood. His father was rector of the church (above), and he would have wandered the isolated lanes thereabouts as a boy. The streams, the rustic bridges, the grand old houses still exist, and are little different from when he knew them. The walled garden in

I’ll start with Tennyson, but offer a word of caution. Look hard at his poetry and you may not see obvious indicators of his Lincolnshire roots. But let me turn it on its head. Visit the village of Somersby, an isolated and lonely hamlet deep in the Wolds of Lincolnshire, the place where he spent his boyhood. His father was rector of the church (above), and he would have wandered the isolated lanes thereabouts as a boy. The streams, the rustic bridges, the grand old houses still exist, and are little different from when he knew them. The walled garden in