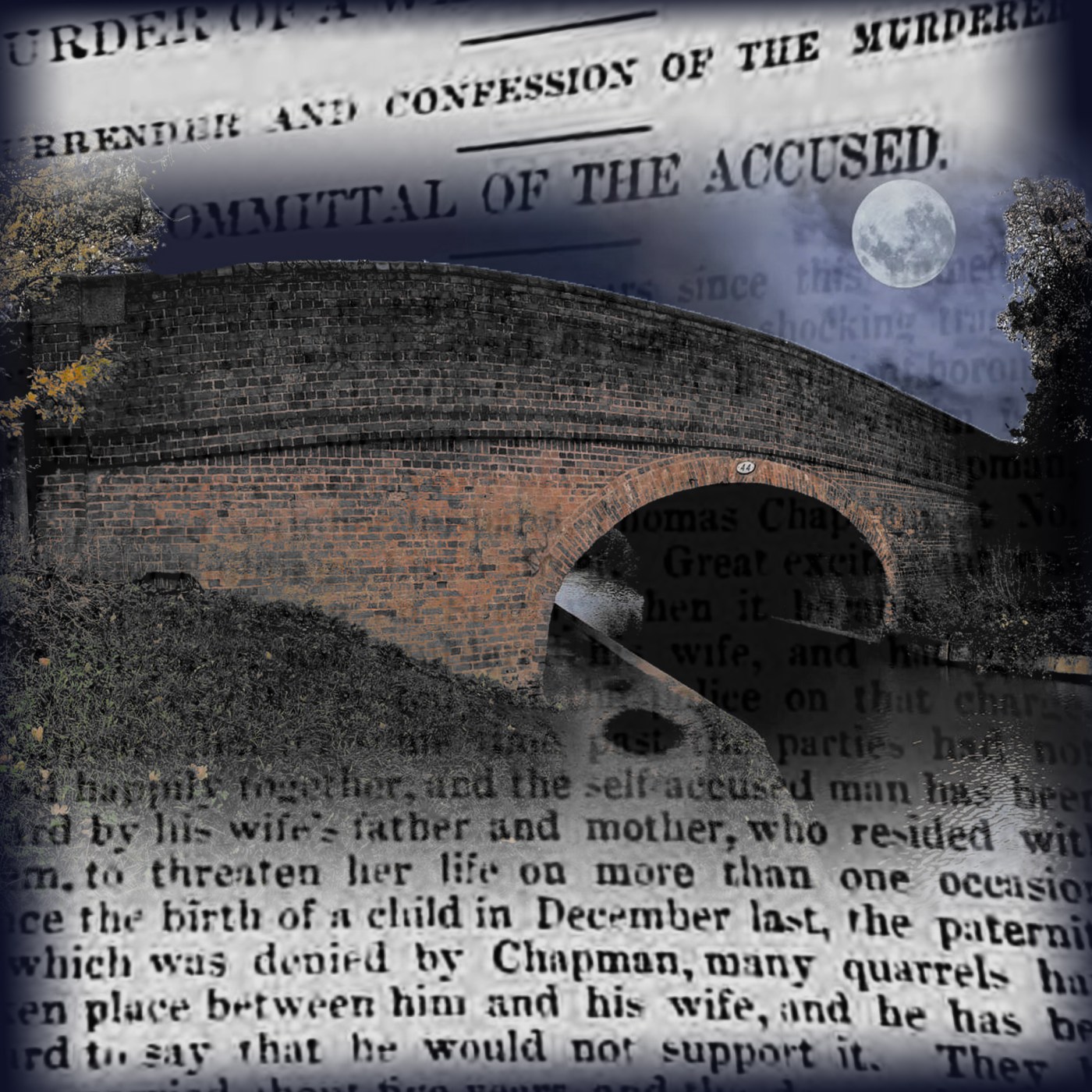

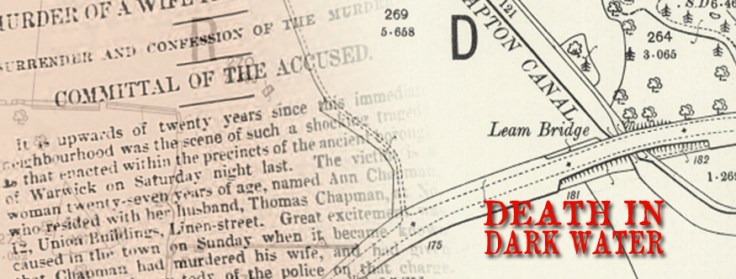

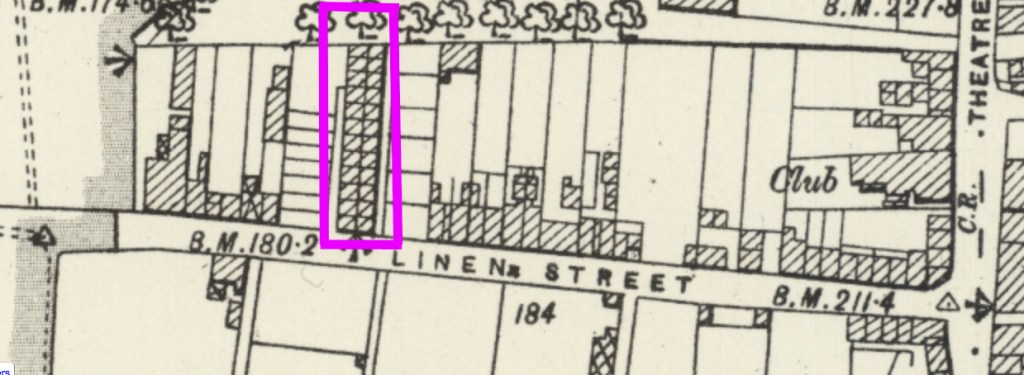

SO FAR – Saturday 16th April, 1870. Thomas Chapman and his wife Ann have gone out for a walk together, leaving heir children at home in Linen Street Warwick, with Ann’s parents. Neither would ever return to that back-to-back terraced house.

Thomas Chapman’s father lived in Friar’s Court, Warwick. At 1.00 am on the morning of 17th April, he was awakened by a loud banging on his front door. Opening it, he was astonished to see his son, bedraggled, and apparently soaked to the skin. He said to his father:

“I have killed Ann, and now I have come home to die with you.”

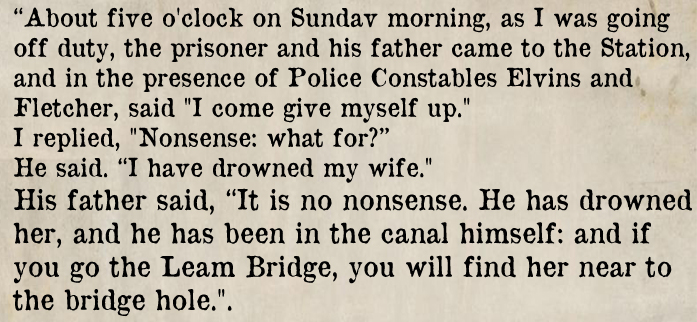

Thinking his son to be either drunk or muddled, the elder Chapman made his son take off his clothes and sent him upstairs to lie down. After a few hours, however, Thomas Chapman convinced his father that he had,indeed, killed Ann,and the air set off together to the police station. PC Satchwell later gave this statement to the magistrates.

Taking Chapman seriously now, a party of constables took drags – large iron rakes on the end of ropes – and set off for Leam Bridge. They noted that there were signs of a struggle on the canal towpath, and they set about the melancholy business of searching for Ann Chapman. After about twenty minutes they found her, and brought her up out of the water. She was taken back to Warwick on a cart, covered in blankets, and Thomas Chapman was charged with her murder.

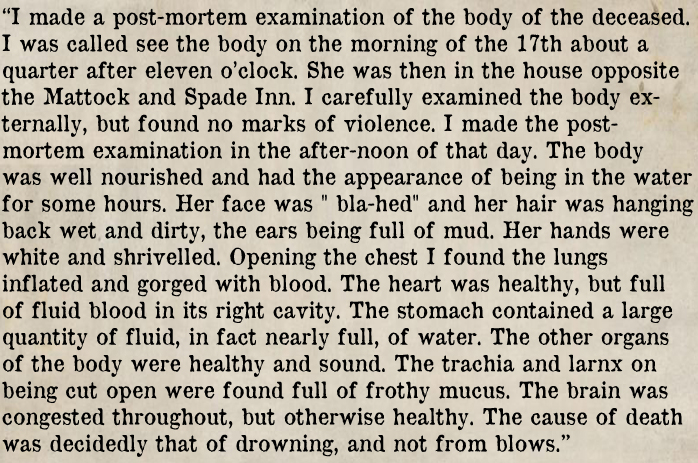

As was usual with these matters, a Magistrate’s hearing and a Coroner’s inquest were quickly convened. At the inquest, Mr Bullock, a surgeon reported what he had found.

Chapman’s confession was graphic, and told of how his grievances against Ann’s behaviour with other men had been festering for some time:

“Last night I went home about six o’clock, and gave my money to her mother. We lived with her. I stayed at home till went out with my wife. I told her we would go to Leamington and look round there. We started a little after nine o’clock. We called at Page’s near the chapel and had a pint of ale. That is all I had all the night. We looked in the shop windows, and went on to Emscote cut bridge. I said, “Come on this way”. She said she did not like to the water side. She was all of a tremble. I said, “What makes you tremble? What have you to tremble for – I said if she would come along there we could get out the Leam Bridge on the Old Road.

We were talking as we were going along the cut side. I said I was sure the last child was not mine. She said none of the children were mine. She said. “No, you scamp, none of them are yours.” She said, “I have deceived you a good while.” When got under the Leam Bridge I pushed her into the water, and as she was going in she laid hold of me and pulled me into the water, I could not get away from her for a long while. She kept fast hold of me. She had liked to have drowned me. I got away from her and got out of the water, and lay down on the grass. I could not walk I was wet. The water was up my chin. I could not touch the bottom.

I threw my old jacket into the water. I got on the Old Road. man passed me against lawyer Heath’s. I made up my mind to drown her before went out of the house. I went my father’s house about one o’clock, changed clothes and lay down on the bed. I have been away from home three months together. When I last came home she held the last child up and said, “Here’s pattern for you; do you think you could get such a one as this ?”

By the time Chapman’s case eventually came to Warwick Assizes, it had clearly dawned on him that it was likely he was going to be hanged, and it was reported that he had been busy trying to convince the authorities that he was insane. What appears to be play-acting cut no ice with the doctors, and they testified that he was perfectly sane, both then and at the time of Ann’s death. Remarkably, the jury – all male, remember – were sufficiently sympathetic with Chapman’s bruised ego that they found him guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter, and he was sentenced to life. What became of him, I don’t know. In those days life meant life, and so it may well be that he died in prison.

What became of the Chapman children is another mystery. The 1871 census has Francis and Mary Dodson – Anna’s parents – living at 12 Union Building, both on ‘Parish Relief’. This had nothing to do with church parishes, but was a form of benefit based on what we now call local government wards. In practice, it was patchy, and depended on the ability of a particular parish to levy rates, and then distribute a portion to the needy.

To me, it is absolutely clear that Thomas Chapman murdered his wife. He pushed her into the murky depths of the Warwick and Napton Canal with one purpose, and one purpose only – to pay her out for her infidelity and taunts about the parentage of her children. His bizarre attempts to convince the authorities that he was insane suggest that he knew he was facing the hangman’s noose. Why judge and jury deemed his crime manslaughter baffles me. What became of him, and whether he survived the Victorian prison system, I cannot say. What I do know is that the dark and gloomy spot where the canal passes under Myton Road is forever tainted by the struggles of a young woman pushed down into the unforgiving depths by an angry and violent man.

Thanks again to Simon Dunne and Steve Bap for the photographs

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot. One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

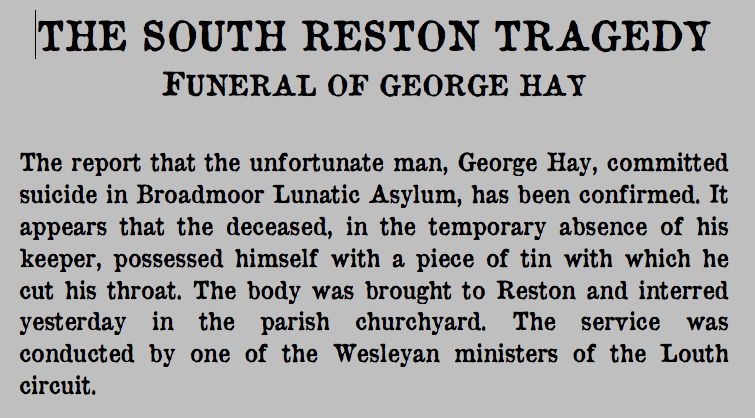

I have been researching and writing about true crimes for many years now and, by their very nature, the events I have described rarely make easy reading. On display is a journey through the very worst of human character, from weakness, via jealousy and insanity, through to pure and simple evil. I can say, however, that the story I am about to tell has been hard to write. It contains descriptions of madness and physical violence which may not be to everyone’s taste, so, if you are squeamish, then maybe this is not for you. Every word of this story is taken from contemporary newspaper reports and transcriptions from a criminal trial that horrified readers in the early summer of 1890.

I have been researching and writing about true crimes for many years now and, by their very nature, the events I have described rarely make easy reading. On display is a journey through the very worst of human character, from weakness, via jealousy and insanity, through to pure and simple evil. I can say, however, that the story I am about to tell has been hard to write. It contains descriptions of madness and physical violence which may not be to everyone’s taste, so, if you are squeamish, then maybe this is not for you. Every word of this story is taken from contemporary newspaper reports and transcriptions from a criminal trial that horrified readers in the early summer of 1890.

Mason is a man given to reflection, and a case from his early career still troubles him. On 30th September 1923, a boy’s body was found near the local church hall. Robert McFarlane had been missing for three days, his widowed mother frantic with anxiety. Mason remembers the corpse vividly. It was almost as if the lad was just sleeping. The cause of death? Totally improbably the boy drowned. But where? And why was his body so artfully posed, waiting to be found?

Mason is a man given to reflection, and a case from his early career still troubles him. On 30th September 1923, a boy’s body was found near the local church hall. Robert McFarlane had been missing for three days, his widowed mother frantic with anxiety. Mason remembers the corpse vividly. It was almost as if the lad was just sleeping. The cause of death? Totally improbably the boy drowned. But where? And why was his body so artfully posed, waiting to be found?

After a few days

After a few days