I’ll start by being mildly controversial; I have been reading crime fiction for sixty years, and I can’t think of another novel which has such a complex plot. Another masterpiece, Chandler’s The Big Sleep certainly has its moments (after all, who did kill the chauffeur?) but even having read The Nine Tailors more than once I would still struggle to write a concise bluffers’ guide to exactly what happens from memory alone. This is neither criticism nor praise; it simply is what it is.

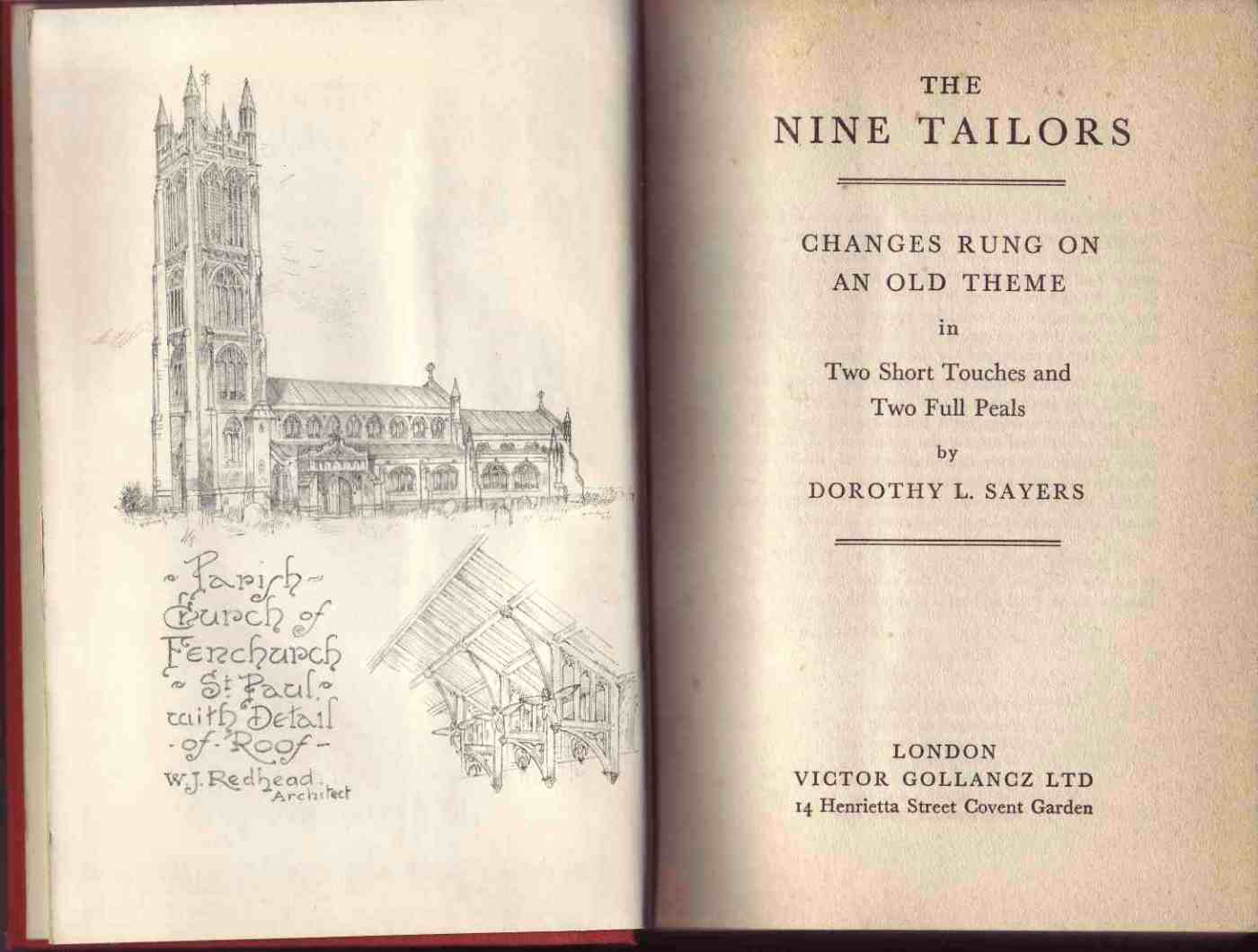

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

The story begins in the depth of the English winter.

“That’s torn it! said Lord Peter Wimsey.

The car lay, helpless and ridiculous, her nose deep in the ditch, her back wheels cocked absurdly up on the bank, as though she were doing her best to bolt to earth, and were scraping herself a burrow beneath the drifted snow……right and left, before and behind, the fen lay shrouded. It was past four o’clock and New Year’s Eve; the snow that had fallen all day gave back a glimmering greyness to a sky like lead.”

Their journey through the Cambridgeshire fens rudely interrupted, Wimsey and Bunter seek help from the nearby village of Fenchurch St Paul. With this simplest of literary devices, Sayers gives Wimsey a perfect excuse to stay overnight, courtesy of the amiable vicar; one of Wimsey’s many skills is bell-ringing and so he joins the church team in their traditional New Year peal, thus embedding him in a labrinthine set of circumstances involving robbery, missing jewels, coded messages, bigamy, deception and murder.

The Nine Tailors are not people, but the ancient bells hanging in the church tower, and Sayers endows them with mystical significance both to the readers of the novel, and to the people in Fenchurch St Paul. Her father was a clergyman, but Sayers later claimed to have had no particular previous knowledge of the arcane lore of church bells. The novel is, however, shot through with references to the bewildering mathematics involved in change ringing. Too much so, for some critics: HRF Keating wrote that Sayers had;

“incautiously entered the closed world of bell-ringing in The Nine Tailors on the strength of a sixpenny pamphlet picked up by chance.”

I am not sure if a book over eighty years old can be subject to plot spoilers, but suffice it to say that, among the several criminals features in the story, the bells do not escape without blame.

So, why is it such a good book, always in print, and often dramatised on screen? Wimsey himself, although deprecatingly described by his creator as a mixture of Bertie Wooster and Fred Astaire, is perhaps the greatest of the gentleman detectives of The Golden Age. He does not patronise the rougher folk of Fenchurch St Paul; he wears his breeding and education lightly and, like Kipling’s ideal man, he can talk with crowds and keep his virtue, and walk with Kings without losing the common touch. Wimsey is a hero of the Great War; this much we know from earlier novels, although his history is alluded to with some subtlety in The Nine Tailors. He has seen the best and worst of men, survived shell shock, and felt the bond between fighting men that transcends class barriers. Sayers was acutely aware of the fact that the horrors of 1914 – 18 pursued men long after the guns fell silent, and incidents in the war play a significant part in the story of The Nine Tailors.

Sayers gives landscape a greater significance in The Nine Tailors than in any of her other books. She was no stranger to Fenland. Her father was rector of Bluntisham, a prosperous village on the edge of the fens, and if you walk in its churchyard, you will see several surnames borrowed and given to characters in The Nine Tailors. The Rev. Henry Sayers later moved to the much more modest parish of Christchurch, slap dab in the middle of the Cambridgeshire fens. Incidentally, that fine writer Jim Kelly happily admits his admiration for Sayers, and set his own novel The Funeral Owl in Christchurch, which he renames Brimstone Hill.

What can the literary traveler find in today’s Cambridgeshire? The fictional Fenland in The Nine Tailors features everything the actual Fenland does. It has drainage rivers named after their width such as The Thirty Foot, back roads called Droves, and clusters of villages with the same name, but modified by the patron saints of their respective churches. Just as she gives us Fenchurch St Paul and Fenchurch St Peter, in real life we have Terrington St Clement, Terrington St John, Wiggenhall St Peter and Wiggenhall St Mary. Sayers takes all the familiar topographical features of the Fens and rearranges them into an authentic but original pattern.

She also teases us with her place names. When we think we have matched Van Leyden’s Sluice with Denver, she confounds us by mentioning that Denver Sluice is much bigger. When you feel certain that Leamholt must be one of the bigger towns such as King’s Lynn, she introduces the actual King’s Lynn in a passing reference.

Here in the Fens, we love our skies and churches while treating with respect the long, arrow-straight, deep black drains which keep our feet dry. Given that large parts of the fens are only inches above sea level we still have cause to fear tidal surges down the Great Ouse and the Nene. No author has ever rivaled Sayers in describing with such power the sheer devastation that the angry waters can bring. Having narrowly escaped death by the bells, Wimsey claws his way to the relative safety of the top of St Paul’s church tower, and looks out on a drowned land:

“The whole world was lost now in one vast sheet of water. He hauled himself to his feet and gazed out from horizon to horizon. To the south-west, St Stephen’s tower still brooded over a dark platform of land, like a broken mast upon a sinking ship. Every house in the village was lit up: St Stephen was riding out the storm. Westward, the thin line of the railway embankment stretched away to Little Dykesey, unvanquished as yet, but perilously besieged. Due south, Fenchurch St Peter, roofs and spire etched black against the silver, was the centre of a great mere. Close beneath the tower, the village of St Paul lay abandoned, waiting for its fate … outward and eastward the gold cock on the weathervane stared and strained, fronting the danger, held to his watch by the relentless pressure of the wind from off The Wash. Somewhere amid that still surge of water, the broken bodies of Will Thoday and his mate drifted and tumbled with the wreckage of farm and field. The Fen had reclaimed its own.”

Read the novel. Absorb the period details and accept the leisurely pace. Hold on firmly to Wimsey’s great sense of compassion and humanity. Wonder at the language and allow yourself a thankful shudder that you are safe at home, dry and warm. I can’t think of a more gripping description of a watery hell, unless it lies in the words of Herman Melville’s Ishmael, clinging to his wooden spar at the end of Moby Dick:

“…his whole captive form folded in the flag of Ahab, went down with his ship, which, like Satan, would not sink to hell till she had dragged a living part of heaven along with her, and helmeted herself with it. Now small fowls flew screaming over the yet yawning gulf; a sullen white surf beat against its watery sides; then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.”

Click on the picture to watch a short reflection in images and music