Crime Fiction’s Most Distinctive Odd Couple? There would be several nominations in this category, were it to be at an awards dinner of some kind. You can make your own suggestions, using whatever criteria you wish; eccentricity, diversity of character and background, problem-solving methods – the choice is yours. I am going for sheer darkness, grim back stories, and an occasional incompatibilty that sometimes verges on the disastrous, but also a symbiotic need for each other that has no sexual element but is unique in the annals of crime fiction If this sounds like the relationship between DCI Carol Jordan and clinical psychologist Dr Tony Hill, then we are spot on.

Val McDermid introduced them to us in 1995, with The Mermaids Singing, and now they are back for the tenth episode in their turbulent career. As we turn the first page, Jordan is already in trouble. She has tried to drink her way out of the life-shattering experience of feeling responsible for the terrible murders of her brother and his wife but, inevitably, one glass too many has resulted in a drink driving charge. Her bosses, not always as supportive, have conspired to declare the breathalyser equipment faulty, and Jordan is aquitted. But, having been tested with the same equipment, so is hell-raising young driver Dominic Barrowclough. When Barrowclough celebrates his freedom by killing himself and four other road users, Jordan’s guilt begins to reach crisis level.

But there is still a job to be done, and in Carol Jordan’s case this is to head up a new police unit, called ReMIT – Regional Major Investigations Team – and their first case is a shocker. In a windswept lay-by on a lonely moorland road, a car is discovered, blazing out of control. When the flames die back sufficiently for the emergency services to get close, the charred remains of a young woman are discovered in the driving seat. The post mortem reveals that she has been strangled, and the blaze started, of all things, by a large box of potato crisp packets. Another such death soon follows, and the ReMIT team discover that they are dealing with a supremely clever killer who befriends his victims at weddings. He ‘crashes’ the wedding with consummate ease, and then targets young women who have attended the wedding unaccompanied. Spinning a yarn that he is a widower still mourning his late wife’s death from cancer, he seems to be the perfect gentleman. Caring, considerate, sexually undemanding – to the unfortunate women he seems like all their Christmases have come at once.

But there is still a job to be done, and in Carol Jordan’s case this is to head up a new police unit, called ReMIT – Regional Major Investigations Team – and their first case is a shocker. In a windswept lay-by on a lonely moorland road, a car is discovered, blazing out of control. When the flames die back sufficiently for the emergency services to get close, the charred remains of a young woman are discovered in the driving seat. The post mortem reveals that she has been strangled, and the blaze started, of all things, by a large box of potato crisp packets. Another such death soon follows, and the ReMIT team discover that they are dealing with a supremely clever killer who befriends his victims at weddings. He ‘crashes’ the wedding with consummate ease, and then targets young women who have attended the wedding unaccompanied. Spinning a yarn that he is a widower still mourning his late wife’s death from cancer, he seems to be the perfect gentleman. Caring, considerate, sexually undemanding – to the unfortunate women he seems like all their Christmases have come at once.

By sheer persistence and a stroke of good fortune, Jordan and her team find themselves a suspect, a young businessman called Tom Elton. But the evidence against him is, at best, circumstantial, and he attends the police interview alongside one of the smartest and most abrasive criminal defence lawyers in the region. Elton is scornful, triumpant, and he literally laughs in the faces of his accusers.

“I thought you lot were supposed to be the elite? I remember the news stories when you were formed. Top Guns, they said,” He scoffed, “Top Bums, more like. If I was your man, I’d be dancing in the streets. With you lot running the show, anyone could get away with murder.”

All the while, as the investigation gathers speed – and then founders – McDermid demonstrates why she is considered by many to be the greatest contemporary British crime writer. The black clouds loom ever lower over Carol Jordan. Her team, some with their own demons to exorcise, look in vain to their boss for inspiration, while Tony Hill, perhaps for the first time in his career, can see no obvious way out of their travails.

Thomas Hardy, in his Wessex novels, was the master of wicked coincidences; a misinterpreted gesture, words said or unsaid, a lover innocently going to the wrong church for her wedding – these all set in train events which will bring the worlds of these characters down around their heads. McDermid creates one here, albeit one very much of the 21st century. and it contributes to the dramatic and totally unexpected finale of this fine novel. Insidious Intent came out in hardback and Kindle in 2017, and this paperback edition will be available on 22nd February from Sphere.

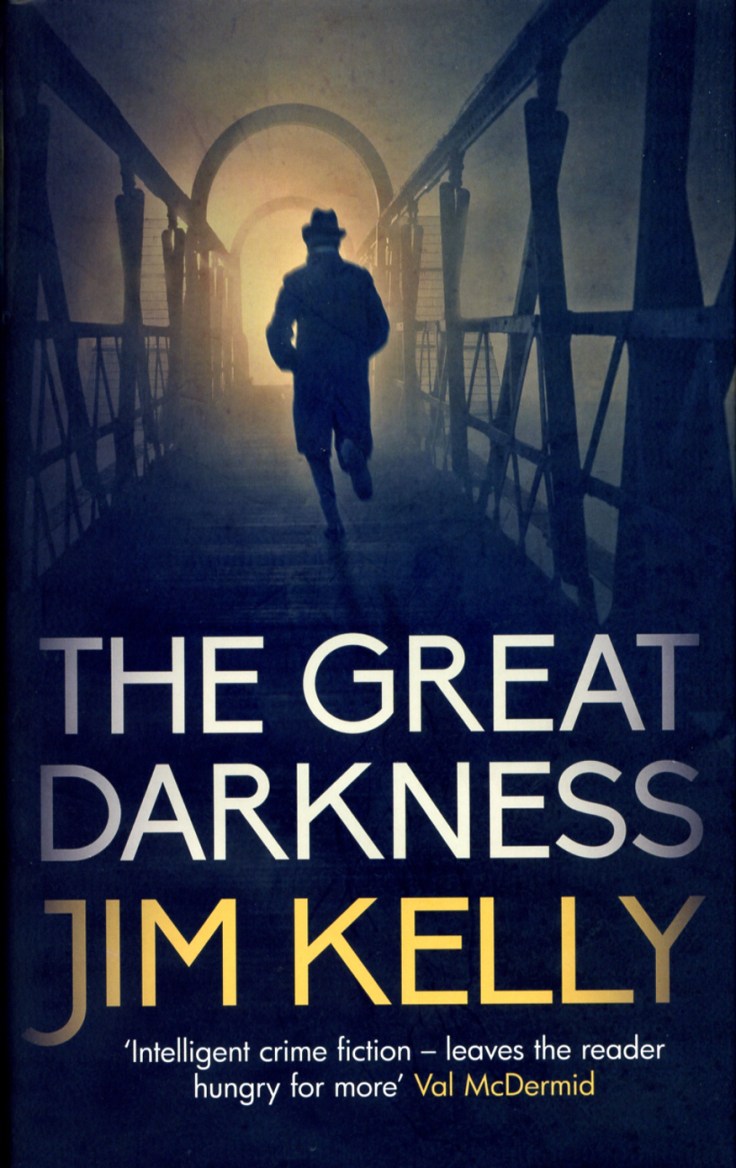

In this febrile atmosphere are many men and women who have memories of “the last lot”. One such is the latest creation from Jim Kelly, (left) Detective Inspector Eden Brooke. He saw service in The Great War, but were someone to wonder if his war had been ‘a good war’, they would soon discover that he had suffered dreadful privations and abuse as a prisoner of the Turks, and that the most physical legacy of his experiences is that his eyesight has been permanently damaged. He wears a selection of spectacles with lenses tinted to block out different kinds of light which cause him excruciating pain. For him, therefore, the nightly blackout is more of a blessing than a hindrance.

In this febrile atmosphere are many men and women who have memories of “the last lot”. One such is the latest creation from Jim Kelly, (left) Detective Inspector Eden Brooke. He saw service in The Great War, but were someone to wonder if his war had been ‘a good war’, they would soon discover that he had suffered dreadful privations and abuse as a prisoner of the Turks, and that the most physical legacy of his experiences is that his eyesight has been permanently damaged. He wears a selection of spectacles with lenses tinted to block out different kinds of light which cause him excruciating pain. For him, therefore, the nightly blackout is more of a blessing than a hindrance.

When it comes to creating a sense of place in their novels, there are two living British writers who tower above their contemporaries. Phil Rickman, (left) in his Merrily Watkins books, has recreated an English – Welsh borderland which is, by turn, magical, mysterious – and menacing. The past – usually the darker aspects of recent history – seeps like a pervasive damp from every beam of the region’s black and white cottages, and from every weathered stone of its derelict Methodist chapels. Jim Kelly’s world is different altogether. Kelly was born in what we used to call The Home Counties, north of London, and after studying in Sheffield and spending his working life between London and York, he settled in the Cambridgeshire cathedral city of Ely.

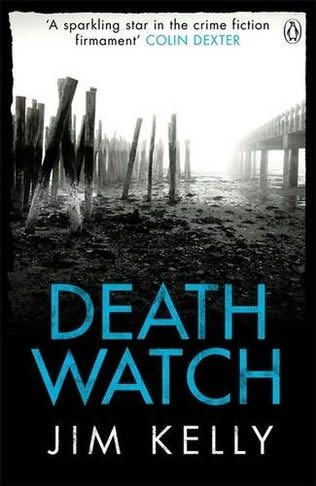

When it comes to creating a sense of place in their novels, there are two living British writers who tower above their contemporaries. Phil Rickman, (left) in his Merrily Watkins books, has recreated an English – Welsh borderland which is, by turn, magical, mysterious – and menacing. The past – usually the darker aspects of recent history – seeps like a pervasive damp from every beam of the region’s black and white cottages, and from every weathered stone of its derelict Methodist chapels. Jim Kelly’s world is different altogether. Kelly was born in what we used to call The Home Counties, north of London, and after studying in Sheffield and spending his working life between London and York, he settled in the Cambridgeshire cathedral city of Ely. It is there that we became acquainted with Philip Dryden, a newspaperman like his creator but someone who frequently finds murder on his doorstep (except he lives on a houseboat, which may not have doorsteps). While modern Ely has made the most of its wonderful architecture (and relative proximity to London) and is now a very chic place to live, visit, or work in, very little of the Dryden novels takes place in Ely itself. Instead, Kelly, has shone his torch on the bleak and vast former fens surrounding the city. Visitors will be well aware that much of Ely sits on a rare hill overlooking fenland in every direction. Those who like a metaphor might well say that, as well as in terms of height and space, Ely looks down on the fens in a haughty fashion, probably accompanying its haughty glance with a disdainful sniff. Kelly (above) is much more interested in the hard-scrabble fenland settlements, sometimes – literally – dust blown, and its reclusive, suspicious criminal types with hearts as black as the soil they used to work on. Dryden usually finds that the murder cases he becomes involved with are usually the result of old grievances gone bad, but as a resident in the area I can reassure you that in the fens, grudges and family feuds very rarely last more than ninety years

It is there that we became acquainted with Philip Dryden, a newspaperman like his creator but someone who frequently finds murder on his doorstep (except he lives on a houseboat, which may not have doorsteps). While modern Ely has made the most of its wonderful architecture (and relative proximity to London) and is now a very chic place to live, visit, or work in, very little of the Dryden novels takes place in Ely itself. Instead, Kelly, has shone his torch on the bleak and vast former fens surrounding the city. Visitors will be well aware that much of Ely sits on a rare hill overlooking fenland in every direction. Those who like a metaphor might well say that, as well as in terms of height and space, Ely looks down on the fens in a haughty fashion, probably accompanying its haughty glance with a disdainful sniff. Kelly (above) is much more interested in the hard-scrabble fenland settlements, sometimes – literally – dust blown, and its reclusive, suspicious criminal types with hearts as black as the soil they used to work on. Dryden usually finds that the murder cases he becomes involved with are usually the result of old grievances gone bad, but as a resident in the area I can reassure you that in the fens, grudges and family feuds very rarely last more than ninety years In the Peter Shaw novels, Kelly moved north. Very often in non-literal speech, going north can mean a move to darker, colder and less forgiving climates of both the spiritual and geographical kind, but the reverse is true here. Shaw is a police officer in King’s Lynn, but he lives up the coast near the resort town of Hunstanton. Either by accident or design, Kelly turns the Philip Dryden template on its head. King’s Lynn is a hard town, full of tough men, some of whom are descendants of the old fishing families. There is a smattering of gentility in the town centre, but the rough-as-boots housing estates that surround the town to the west and the south provide plenty of work for Shaw and his gruff sergeant George Valentine. By contrast, it is in the rural areas to the north-east of Lynn where Shaw’s patch includes expensive retirement homes, holiday-rental flint cottages, bird reserves for the twitchers to twitch in, and second homes bought by Londoners which have earned places like Brancaster the epithet “Chelsea-on-Sea.”

In the Peter Shaw novels, Kelly moved north. Very often in non-literal speech, going north can mean a move to darker, colder and less forgiving climates of both the spiritual and geographical kind, but the reverse is true here. Shaw is a police officer in King’s Lynn, but he lives up the coast near the resort town of Hunstanton. Either by accident or design, Kelly turns the Philip Dryden template on its head. King’s Lynn is a hard town, full of tough men, some of whom are descendants of the old fishing families. There is a smattering of gentility in the town centre, but the rough-as-boots housing estates that surround the town to the west and the south provide plenty of work for Shaw and his gruff sergeant George Valentine. By contrast, it is in the rural areas to the north-east of Lynn where Shaw’s patch includes expensive retirement homes, holiday-rental flint cottages, bird reserves for the twitchers to twitch in, and second homes bought by Londoners which have earned places like Brancaster the epithet “Chelsea-on-Sea.”