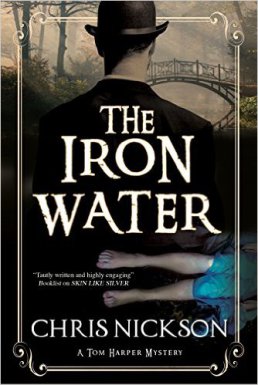

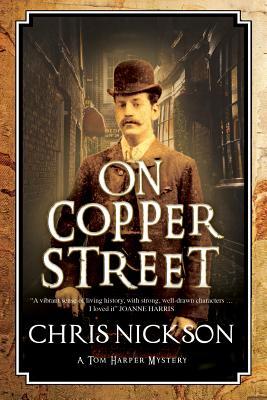

I have become a huge admirer of the writing of Chris Nickson (left) . He says on his website:

I have become a huge admirer of the writing of Chris Nickson (left) . He says on his website:

“I’ve written since I was a boy growing up in Leeds. It all really began with a three-paragraph school essay telling a tale of bomb disposal when I was 11. Like a lightbulb switching on, it brought the revelation that I enjoyed telling stories. Along the way came diversions into teenage poetry, and my other great love, music, as both a bassist and then a singer-songwriter-guitarist. At 21, I moved to the US, and spent the next 30 years there, returning to England in 2005, and finally full circle to Leeds.”

I first read – and thoroughly enjoyed – his books featuring Detective Inspector Tom Harper, and relished his recreation of the smoky, noisy and turbulent city of Leeds in the 1890s. Next, for me, came his Leeds during WWII, as seen through the eyes of Womens’ Auxiliary Police Constable Lottie Armstrong. I had not, until now, gone back to the eighteenth century to investigate Nickson’s tales of the town’s Constable, Richard Nottingham. It seems that Nickson had ushered Nottingham into a well-deserved retirement but, rather like the resurrection, by popular demand, of Sherlock Holmes after his apparent demise at the Reichenbach Falls, Nottingham has returned to duty in Free From All Danger.

You will be pushed to find better opening words to a novel even were you to search all year:

You will be pushed to find better opening words to a novel even were you to search all year:

“Sometimes he felt like a ghost in his own life. The past had become his country, so familiar that its lanes and byways were printed on his heart.”

Thus we learn that Richard Nottingham has his best years behind him. With stiffened limbs and diminished vigour he has withdrawn to his home and family – although that family has been diminished by tragedy. When Simon Kirkstall, his successor as town Constable dies, he is persuaded by The Mayor to return to his old job, at least temporarily, while a suitable successor is found.

We are in the year of Our Lord 1736, November, and winter seems to have come early. As Nottingham dusts off his old working clothes he is immediately called into action when a body is pulled from the river. This is no drowning, as the savage slash wounds on the man’s throat testify all too readily. It is as if someone out there in the cobbled lanes, dank ginnels and misty river banks of the rapidly expanding wool town has learned of Nottingham’s return and is determined to challenge him. Murder follows murder, but despite their best efforts neither Nottingham nor his deputy Rob Lister are coming anywhere near to identifying either the assailants or their motives.

As the November 5th celebration approaches, with huge bonfires being assembled across the town, Nottingham is convinced that the killers – who have been identified as a man and his two sons – are going to target a significant victim while the fires blaze and the mill apprentices drink themselves stupid and taunt the forces of law and order.

In Nickson’s writing you will find neither false flourishes nor furbelows. He doesn’t show off, nor does he have time for tricks and verbal trinkets. Bear in mind that he is a songwriter, and you will understand that he knows how to tell a story with the minimum of fuss. Free From All Danger is a straightforward – but impressive – police procedural, albeit one set in a time when the procedures were based on the wisdom and intuition of the coppers, rather than a two-hundred page manual.

If you have any appreciation of good storytelling, you will enjoy this book. You will, however, need fingerless gloves, warm socks and a good woollen vest, preferably woven in Yorkshire. This November in Leeds is cold. It is a cold that gnaws at men’s bones, chills their souls, and has them heading for the hearths of home, or the fireside of a crowded inn. The cobbles glint with frost, and the mist from the rivers and becks conceals a multitude of dark deeds. Free From All Danger is historical crime fiction right out of the top drawer. It is published by Severn House, and is available here. Please take the time to read Fully Booked reviews of more Chris Nickson novels. Just click on the images below.

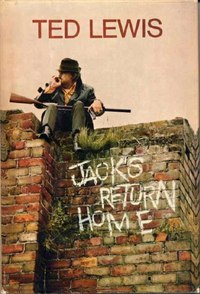

In 1965, All the Way Home and All the Night Through was published. It is a thinly disguised autobiographical novel, but Lewis’s breakthrough came in 1970 with the publication of Jack’s Return Home. The title was, bizarrely, taken from a spoof melodrama acted out by Tony Hancock, Hattie Jacques, Sid James and Bill Kerr as an episode of Hancock’s Half Hour. The novel, however, has few laughs. It describes the revenge mission of a London-based enforcer, Jack Carter, as he returns to his northern home town to investigate the death of his brother. The novel was adapted and filmed as Get Carter, and the rest, as they say, is history. Fame – and money – did not sit comfortably on Lewis’s shoulders, however. A mixture of drink and personal demons led to the break-up of his marriage, and a solitary return to Barton to live with his widowed mother. He died there, of heart failure connected to his ruinous drinking, in 1982.

In 1965, All the Way Home and All the Night Through was published. It is a thinly disguised autobiographical novel, but Lewis’s breakthrough came in 1970 with the publication of Jack’s Return Home. The title was, bizarrely, taken from a spoof melodrama acted out by Tony Hancock, Hattie Jacques, Sid James and Bill Kerr as an episode of Hancock’s Half Hour. The novel, however, has few laughs. It describes the revenge mission of a London-based enforcer, Jack Carter, as he returns to his northern home town to investigate the death of his brother. The novel was adapted and filmed as Get Carter, and the rest, as they say, is history. Fame – and money – did not sit comfortably on Lewis’s shoulders, however. A mixture of drink and personal demons led to the break-up of his marriage, and a solitary return to Barton to live with his widowed mother. He died there, of heart failure connected to his ruinous drinking, in 1982.

The centrepiece of Triplow’s book is, quite rightly, concerned with the novel itself, and its journey from a brutally honest and ground-breaking novel through to a partial re-imagining as one of the finest crime films ever made. Of Jack Carter, Triplow stresses that, despite the iconic image created by Michael Caine and director Mike Hodges

The centrepiece of Triplow’s book is, quite rightly, concerned with the novel itself, and its journey from a brutally honest and ground-breaking novel through to a partial re-imagining as one of the finest crime films ever made. Of Jack Carter, Triplow stresses that, despite the iconic image created by Michael Caine and director Mike Hodges Aside from describing what must have been harrowing conversations with Lewis’s widow and children, Triplow employs both the depth and breadth of his knowledge of British crime fiction to convince us just how good Ted Lewis was. It is intriguing that Triplow, supported by no less an authority than the magisterial Derek Raymond, makes a fascinating case for GBH being the apotheosis of Lewis’s talent, despite the groundbreaking style and success of Jack’s Return Home. Getting Carter is a sober and sombre account of the life of a man whose talent both defined and destroyed him, and Triplow makes no attempt to sanitise his subject. Lewis was clearly a man of huge personal charm when not in the grip of drink, but from the early days of illegally bought pints of beer in the 1950s through to the grim years of decline and death, alcohol had him firmly by the throat.

Aside from describing what must have been harrowing conversations with Lewis’s widow and children, Triplow employs both the depth and breadth of his knowledge of British crime fiction to convince us just how good Ted Lewis was. It is intriguing that Triplow, supported by no less an authority than the magisterial Derek Raymond, makes a fascinating case for GBH being the apotheosis of Lewis’s talent, despite the groundbreaking style and success of Jack’s Return Home. Getting Carter is a sober and sombre account of the life of a man whose talent both defined and destroyed him, and Triplow makes no attempt to sanitise his subject. Lewis was clearly a man of huge personal charm when not in the grip of drink, but from the early days of illegally bought pints of beer in the 1950s through to the grim years of decline and death, alcohol had him firmly by the throat.

The Last Squadron is a military thriller from debut author Dan Jayson, and it is set fifteen years from now, and the most pessimistic soothsayers have been proved right. The ethnic and religious schisms which had been festering for decades have bloomed into an apocalyptic hell of different wars across the globe. Nowhere is safe, and unlikely political alliances have been forged. A squadron of mountain troops has been serving on the inhospitable Northern Front, but as they fly home for much needed rest, their aircraft is shot down – and they realise that their nightmare is only just beginning. Dan Jayson’s bio tells us that he is the co-founder of an underwater search and salvage company. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Marine Engineers and served in the British Territorial Army. He is based in south-west London.The Last Squadron is published by Matador, and is

The Last Squadron is a military thriller from debut author Dan Jayson, and it is set fifteen years from now, and the most pessimistic soothsayers have been proved right. The ethnic and religious schisms which had been festering for decades have bloomed into an apocalyptic hell of different wars across the globe. Nowhere is safe, and unlikely political alliances have been forged. A squadron of mountain troops has been serving on the inhospitable Northern Front, but as they fly home for much needed rest, their aircraft is shot down – and they realise that their nightmare is only just beginning. Dan Jayson’s bio tells us that he is the co-founder of an underwater search and salvage company. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Marine Engineers and served in the British Territorial Army. He is based in south-west London.The Last Squadron is published by Matador, and is  David Gilbertson (right) is a writer whose knowledge of policing and counter-terrorism is second to none. He had a long and varied career as a police officer. He served in uniform and CID in the UK and abroad, (attached to the New York City Police Department in 1988 and seconded to South Africa in 1994 as the Director of Peace Monitors for the first post-Apartheid elections). His latest novel, The Path of Deception, is set in a Britain devastated by a terrorist atrocity of hitherto unimagined scale. The police and security services are faced with the very real possibility that their attempts to prevent the outrage have been sabotaged from within. Suddenly, the task of making safe the imminent coronation of King Charles III is thrown into a very different focus. You can read more on the

David Gilbertson (right) is a writer whose knowledge of policing and counter-terrorism is second to none. He had a long and varied career as a police officer. He served in uniform and CID in the UK and abroad, (attached to the New York City Police Department in 1988 and seconded to South Africa in 1994 as the Director of Peace Monitors for the first post-Apartheid elections). His latest novel, The Path of Deception, is set in a Britain devastated by a terrorist atrocity of hitherto unimagined scale. The police and security services are faced with the very real possibility that their attempts to prevent the outrage have been sabotaged from within. Suddenly, the task of making safe the imminent coronation of King Charles III is thrown into a very different focus. You can read more on the  Crime reporter Colin Crampton (as imagined by Frank Duffy, left) is a delightful invention by journalist and author Peter Bartram. Only he could verify the extent to which Colin is autobiographical, but suffice it to say that Bartram has spent in his working life in journalism, and knows Brighton in and out, top to bottom, and backwards and forwards. In Front Page Murder, Crampton once again becomes involved in a very literal matter of life and death. Set in the 1960s before the abolition of the death penalty, Crampton is persuaded to establish the innocence of Archie Flowerdew – awaiting the hangman’s noose for the murder of a rival artist. Peter Bartram wrote an excellent piece for Fully Booked on the peculiarly English attraction known as What The Butler Saw machines, and you can read the entertaining feature

Crime reporter Colin Crampton (as imagined by Frank Duffy, left) is a delightful invention by journalist and author Peter Bartram. Only he could verify the extent to which Colin is autobiographical, but suffice it to say that Bartram has spent in his working life in journalism, and knows Brighton in and out, top to bottom, and backwards and forwards. In Front Page Murder, Crampton once again becomes involved in a very literal matter of life and death. Set in the 1960s before the abolition of the death penalty, Crampton is persuaded to establish the innocence of Archie Flowerdew – awaiting the hangman’s noose for the murder of a rival artist. Peter Bartram wrote an excellent piece for Fully Booked on the peculiarly English attraction known as What The Butler Saw machines, and you can read the entertaining feature