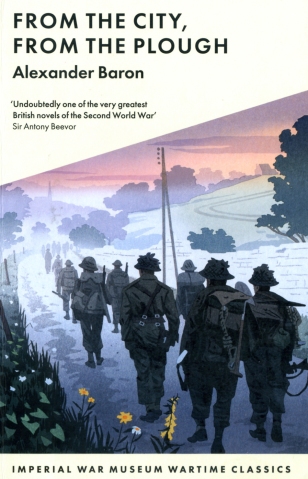

his 1948 best seller echoes Alexander Baron’s own military career as it follows a battalion of a fictional infantry brigade as they prepare for – and then take part in – D Day in the summer of 1944. The Fifth Wessex is, as the book’s title suggests, made up of a mixture of clumsy red-cheeked farm boys from the chalk uplands, well-read introverts who keep themselves to themselves, streetwise chancers and bewildered lads who are virgins in both bedroom and battlefield. They could be soldiers from earlier wars, and their ancestors might have known Agincourt, Marston Moor, Malplaquet, Talavera, Spion Kop and Arras. Baron has no time for the thinly veiled homo-eroticism of some of the Great War writers. His men can be uncouth, foul-mouthed, brutalised by their social background, yet given to moments of great compassion and charity.

his 1948 best seller echoes Alexander Baron’s own military career as it follows a battalion of a fictional infantry brigade as they prepare for – and then take part in – D Day in the summer of 1944. The Fifth Wessex is, as the book’s title suggests, made up of a mixture of clumsy red-cheeked farm boys from the chalk uplands, well-read introverts who keep themselves to themselves, streetwise chancers and bewildered lads who are virgins in both bedroom and battlefield. They could be soldiers from earlier wars, and their ancestors might have known Agincourt, Marston Moor, Malplaquet, Talavera, Spion Kop and Arras. Baron has no time for the thinly veiled homo-eroticism of some of the Great War writers. His men can be uncouth, foul-mouthed, brutalised by their social background, yet given to moments of great compassion and charity.

The British officer class have been long the object of scorn in both poetry and prose, but Baron deals with them in a largely sympathetic way. Those leading the Fifth on the ground are decent fellows; people who are only too aware of the frequently uneven struggle between shards of steel and the breasts of brave men. Even the Brigadier, whose plans prove so costly, is well aware of what he asks. He is, however, resolute in the way he shuts down his personal qualms in order to maintain the integrity of the battle plan. The one exception is the odious Major Maddison, a cold and sexually troubled narcissist whose demise is as satisfying as it is inevitable.

The British officer class have been long the object of scorn in both poetry and prose, but Baron deals with them in a largely sympathetic way. Those leading the Fifth on the ground are decent fellows; people who are only too aware of the frequently uneven struggle between shards of steel and the breasts of brave men. Even the Brigadier, whose plans prove so costly, is well aware of what he asks. He is, however, resolute in the way he shuts down his personal qualms in order to maintain the integrity of the battle plan. The one exception is the odious Major Maddison, a cold and sexually troubled narcissist whose demise is as satisfying as it is inevitable.

It is worth comparing From The City, From The Plough to another deeply moving novel of men at war, Covenant With Death, (1961) by John Harris. Both deal at length with preparation for an assault; both conclude with the devastating outcome. In Harris’s book the ‘band of brothers’ is a thinly fictionalised Pals Battalion from a northern city. Their Gehenna is the morning of July 1st 1916 and if it is just as brutal as the fate of the Fifth Wessex, it is perhaps more shocking for its suddenness. Harris concludes his book with the words;

“Two years in the making. Ten minutes in the destroying. That was our story.”

aron writes lyrically about the midsummer grace of the French countryside, its orchards and abundance of wild flowers, some of which grace the helmets and tunics of the passing soldiers, their fragility which will contrast cruelly with the total vulnerability of the crumpled and shattered bodies of the men who wore them. For the driven and exhausted men of the Fifth Wessex, unlike their fathers before them, there is always a new unspoiled hillside, a grove of trees untouched by shellfire, a fresh sunken lane lined with roses and willow herb. For the war in Normandy is a war of movement. A field reeking with the blood of dead horses and cattle is soon left behind, as the Brigadier stabs his finger at the map and finds another bridge, another crossroads and another copse that must be taken.

aron writes lyrically about the midsummer grace of the French countryside, its orchards and abundance of wild flowers, some of which grace the helmets and tunics of the passing soldiers, their fragility which will contrast cruelly with the total vulnerability of the crumpled and shattered bodies of the men who wore them. For the driven and exhausted men of the Fifth Wessex, unlike their fathers before them, there is always a new unspoiled hillside, a grove of trees untouched by shellfire, a fresh sunken lane lined with roses and willow herb. For the war in Normandy is a war of movement. A field reeking with the blood of dead horses and cattle is soon left behind, as the Brigadier stabs his finger at the map and finds another bridge, another crossroads and another copse that must be taken.

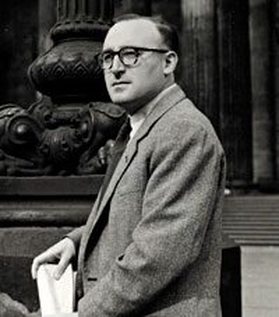

The heroes in From The City, From The Plough come in all shapes and sizes, but there are no winners. Let Alexander Baron (right) have the last word.

The heroes in From The City, From The Plough come in all shapes and sizes, but there are no winners. Let Alexander Baron (right) have the last word.

“Among the rubble, beneath the smoking ruins, the dead of the Fifth Battalion sprawled around the guns they had silenced; dusty, crumpled and utterly without dignity; a pair of boots protruding from a roadside ditch; a body blackened and bent like a chicken burnt in the stove; a face pressed into the dirt; a hand reaching up out of a mass of brick and timbers; a rump thrust ludicrously towards the sky. The living lay among them, speechless, exhausted, beyond grief or triumph, drawing at broken cigarettes and watching with sunken eyes the tanks go by.”

September 8, 2019 at 1:34 pm

Thank you so much for this wonderful Blog Tour support x

LikeLike